The morning of July 1 last summer began like any other for Peter Hahn, a 74-year-old who had come to do extraordinary things in a place that he would never call godforsaken but which, nonetheless, is.

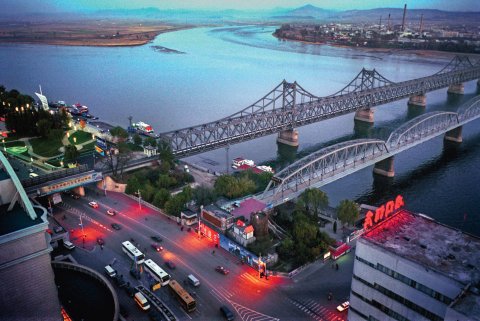

Tumen, China, sits on the border with North Korea; it's a gritty city of 140,000, more than half of which is ethnically Korean. Like most of the region fronting this desolate border, it is poorer than much of the rest of eastern China. This is where, in 1997, Hahn decided to set up shop with his wife, Eunice, abandoning their comfortable life in suburban Los Angeles to pursue what would become his life's work: trying to help the impoverished people on both sides of the border—but in particular those from North Korea, where, in 1942, Hahn was born, in Wonsan, 90 miles east of Pyongyang. He lived there as a child before his family moved to the South.

After moving to China almost 20 years ago, Hahn set up a vocational school in Tumen, one that trained poor kids in everything from cooking to auto repair to English. He set up an industrial-scale bakery on the North Korean side of the border, bringing in wheat and flour from China to feed North Koreans. He then got permission from the government to build a fertilizer plant, and then a food processing plant in a new "special economic zone" in the northeast corner of North Korea. "We feed 22,000 people a day," he told a reporter for The Sydney Morning Herald.

At the core of his decision to move to the China–North Korea border—and all the charitable work that followed—is Hahn's faith. Like many of the aid and nongovernmental organization workers who assist North Koreans, Hahn is an evangelical Christian, called to what he believes is a sacred duty to help those who drew what is surely one of the shortest straws on this planet: the citizens of North Korea, the world's most despotic regime. And it is because of his faith that Hahn's world got torn apart that July morning, and he became yet another victim of a vanishing tolerance on both sides of the border for the work he and Christians like him pursue. Caught between countries run by Kim Jong Un to his east and by Xi Jinping to his west, Hahn now sits in a detention center, first placed under house arrest that morning in July, then formally detained last November.

The Last Bond Bad Guy

When Kim came to power in Pyongyang three years ago, there was, inevitably, very little known about him (they don't call it the Hermit Kingdom for nothing). His father and predecessor in the dynastic regime that reigns in North Korea had appalled and unnerved the world. Kim Jong Il presided over the worst famine of modern times, one in which at least 500,000 North Koreans died in the 1990s, while at the same time building a nuclear bomb that remains the cornerstone of North Korean security—the ultimate Don't screw with us or you know what you'll get card.

Kim Jong Un had gone to prep school in Switzerland for a couple of years, which meant that those of us who cover North Korea could talk to people who knew him. (What a concept.) What we discovered was surprising and encouraging. Among other things, he loved the NBA. He was a fan of the 1990s Chicago Bulls, for God's sake, and he worshipped both Michael Jordan and Dennis Rodman. Surely this faint whiff of normality had to be a good sign, right? So we wrote that the portly young man could not possibly be the out-of-central-casting Dr. Evil his father was, with the buffoonish sunglasses and the idiotic pompadour. And whatever the case, he was so young (29 when his father died) and inexperienced that there was no way he was going to run the country for very long; that task would surely be left to a regent, Kim Jong Un's uncle, Jang Sung Thaek. Jang had been one of seven elderly officials who accompanied Kim Jong Il's funeral bier through the streets of Pyongyang in December 2011. He was said to be trusted by the Chinese. He'd clearly be running the show.

That prediction turned out to be fanciful. The next time some of us who try to follow North Korea from afar had any news from there, it was, given what we had written, shocking: Kim had had Jang killed. (According to one unconfirmed report, he had him fed to attack dogs.) Suddenly the images of the young Kim playing hoops in Switzerland wearing a Rodman jersey seemed not so cute.

Then came the storm over Sony's The Interview, a movie that portrays the dictator as a weakling who is assassinated by two bumbling American journalists, and the extraordinary cyberhack into Sony Pictures, which the FBI insists was executed by North Korea. ("We believe [the hack] was carried out by perhaps overzealous underlings who believed they should defend the leader's honor," says a South Korean intelligence officer.) Now, alas, the outside world is getting a better idea of who Kim Jong Un is.

Sitting at a coffee shop in Seoul, an old friend of Hahn's, a Christian activist with long experience working in China and aiding North Koreans, says neither he nor his colleagues are surprised by any of this. Ask him when the crackdown on those working to help North Koreans escape began and he doesn't hesitate: "Three years ago, almost exactly when Kim Jong Un came to power.''

The work activists and missionaries do for North Koreans comes in two parts. Some, like Hahn, deliver goods and services to citizens inside the country. Others work to smuggle people into China, and ultimately to South Korea—the so-called "underground railroad" that has grown significantly over the past 15 years. These refugees—there are now 27,000 former North Koreans in the South—often tell horrific stories about life in the North, stories Kim Jong Un evidently finds embarrassing and possibly threatening. Those who make it out usually send money back to relatives in the North and often work with smugglers to get other family members out. They are also often able to phone family members in the North, and thus able to inform them of what life is like in the outside world. That has always made North Korean authorities uncomfortable.

Thus, since Kim came to power, Christian activists say that Pyongyang has ramped up efforts to stanch the flow of defectors. Among the methods, both activists and South Korean government sources say, is a change in policy aimed at North Korean border guards. They have apparently been told they can keep the bribes North Korean middlemen pay them to look the other way when refugees cross into China…provided they report on who it is that gave them the bribes and when. Kim has also apparently reduced the punishments for first-time offenders who cross the border and are forcibly repatriated by the Chinese. In the past, that was a guaranteed multiyear prison sentence. Now, according to one source, the punishment is a relatively short stint in a "re-education camp."

The methods are working, sources say. Though accurate estimates are hard to come by, sources involved in the underground railroad all say the number of "travelers" last year was down significantly from 2011, Kim Jong Il's last year in power. South Korea's Ministry of Unification estimates that the number has been cut in half, from nearly 3,000 in 2011 to just below 1,400 last year.

The Brutal Missionary Position

Hahn's associates insist he had not been directly involved in the underground railroad for more than a decade. His focus has been on his vocational school and feeding North Koreans across the border. "He understood that being involved in the underground railroad would jeopardize his ability to help North Koreans in North Korea, so he has kept his distance from that, very purposefully," says one missionary in China.

What is unclear now is whether Kim's effort to stem the flow of refugees from North Korea is in any way coordinated with the Chinese government's crackdown on those providing them aid. Beijing has begun allowing North Korean agents across the border to round up refugees. Beyond that, the conventional view is that there is not much coordination, for one very obvious reason. Since Xi Jinping came to power, in November 2012, relations between Pyongyang and its lone ally, China, have been chilly at best. Xi, not surprisingly, does not view Kim as an equal; he is said to view him as inexperienced and unqualified. Beijing has apparently leaned hard on Pyongyang to not undertake a fourth test of a nuclear weapon—something Kim is, according to intelligence sources in the region, eager to do. "The Chinese have told [Pyongyang] that they will not have their back if they conduct another test," says an official in Seoul. And officials in Seoul may well know. Xi has been on a charm offensive with South Korea, and surprised everyone when he visited there (last July), before visiting North Korea or inviting Kim to Beijing.

Whether coordinating with Pyongyang or not, Xi has his own reasons for cracking down on the flow of North Koreans into China, as well as the Christian activists in his country. In December, a North Korean soldier who had fled the country allegedly killed four Chinese citizens in a botched robbery attempt in the village of Nanping, just north of the Tumen River.

But the crackdown predates that incident. Xi is a nationalist, and at times—such as when he has spoken about his vision of "The China Dream"—he sounds like an American politician extolling "The American Dream." That nationalism shows its hard edge when it comes to foreign influence in China. He has come down hard on foreign technology and media companies, and the government now even tries to disrupt the virtual private networks that let China's Internet users have unfettered access to information on the Net.

His evident mistrust of foreign influences plainly extends to religion. Christianity has for decades been the fastest growing religion in China. There are "official" churches in which the officials are approved by Beijing, and then there are underground "house" churches, which are where much of the growth has been, fueled mostly by evangelicals. Scholars estimate there are now roughly 70 million practicing Christians in China, out of a population of 1.3 billion.

Last summer, the government made a show of destroying a new church in Wenzhou, a prosperous city in Zhejiang province and home to many Christians. Large protests followed, but the government didn't back down. That was a clear warning, Christian activists say, that the continued growth of independent house churches would no longer be tolerated.

Foreign activists working with NGOs or other aid organizations within China are an easy target for the government. In addition to Hahn's being placed under house arrest, all his financial assets there were frozen (hindering greatly the work his various operations do). A month later, two Christian aid workers—Kevin and Julia Garratt, a Canadian couple—were arrested and charged with espionage—in particular, stealing military secrets. The Garratts ran a coffee shop in the border city of Dandong, China, and used the proceeds, several activists say, to aid North Koreans. "The fact that they would be charged with stealing military secrets just shows that the government doesn't even care about coming up with a credible case when it comes to dealing with us," says one Christian activist who has close ties to both China and North Korea and who knows the Garratts. "I mean, it's just laughable." Overall, activists say that last year hundreds of South Korean aid workers—almost all Christians—were kicked out of China, mainly by being denied visa renewals.

Hahn's arrest, some in the Christian community say, may have come with an inadvertent assist from the U.S. government. In the spring of 2013, State Department diplomat Robert King, the U.S. special envoy for North Korean human rights issues, made a high-profile visit to the China-North Korea border, and met with students at Hahn's vocational school. However well-intentioned the visit—State says it was simply to highlight the good work an American citizen was doing for poor children—Beijing was not amused, activists in and outside of China say. King then scheduled another visit to the border region for the following summer—August 2014. Hahn's house arrest began July 1. Missionaries and friends of Hahn's now grumble that the two dates are highly significant.

Hahn may have done things that were also naive, given his long experience in China. He was working on a plan to get the U.N. to help him bring volunteers to North Korean aid projects, a somewhat grandiose ambition given that he was organizing and apparently planned this fledgling organization from China. "That's just a nonstarter in China, and Peter should have known that," says a friend.

In November, the government formally arrested Hahn and moved him to the detention center in Longjing, China. He is suspected, the government says, of embezzlement and signing fraudulent invoices, allegations that could lead to a multiyear jail term. Hahn's lawyer, Shanghai-based Zhang Peihong, calls the charges "groundless."

To date, Hahn's family is frustrated because despite monthly visits from officers from the U.S. consulate in Shenyang, China, he is not getting medicines he needs to treat a prostate condition. They also wonder whether the case is getting adequate attention from the U.S. government. The State Department says it is doing its utmost to win Hahn's release.

In the immediate aftermath of her husband being placed under house arrest, Eunice Hahn, 67, fled to Seoul, where she remains, awaiting a trial for Peter that still has not been scheduled. Given that one may be imminent, she declines to talk to the press about the case, but upon arriving in South Korea last summer, she told a reporter, "I feel that the Chinese government doesn't want foreign NGOs working on North Korea anymore. In the past, it just left us alone, but now it is cracking down."

That certainly appears to be the case, and even if Kim doesn't get any respect these days from his elders in Beijing, it's a policy that the portly little dictator in Pyongyang supports. Like Xi Jinping in Beijing—butagainst most expectations—Kim Jong Un has consolidated power in Pyongyang, and he is plainly determined to run his country with a tightening grip. And at just 32, he is likely to be around for a long, long time.