Sam Walker walked out of school in January 1965 and headed for Brown Chapel AME Church. He knew that once he picked up his placard and joined the other activists heading for the courthouse, he might be arrested by the racist sheriff, Jim Clark, and thrown in jail. But he was not deterred...even though he was only 11 years old.

On January 2, 1965, Martin Luther King Jr. helped break an illegal injunction against public assembly and freedom of speech in Selma, Alabama, with a massive public rally. Sixteen days later, protests began, mostly composed of local students. Most were in high school, but Walker tagged along with his 16-year-old brother, Willie. "The first time I was arrested I was with one of Willie's friends, and the second time I was with my brother, so I wasn't scared," Walker recalls. "They shoved about 15 or 20 people in a cell meant to house one or two people."

Across the South—in Atlanta, Georgia; Memphis, Tennessee; Greensboro, North Carolina; and Montgomery, Alabama—museums have material on the civil rights struggle of the 1950s and 1960s. Most are larger and have more impressive displays than the National Voting Rights Museum and Institute in Selma, but Sam Walker's presence as historian and tour guide makes its presentation perhaps the most memorable experience of them all.

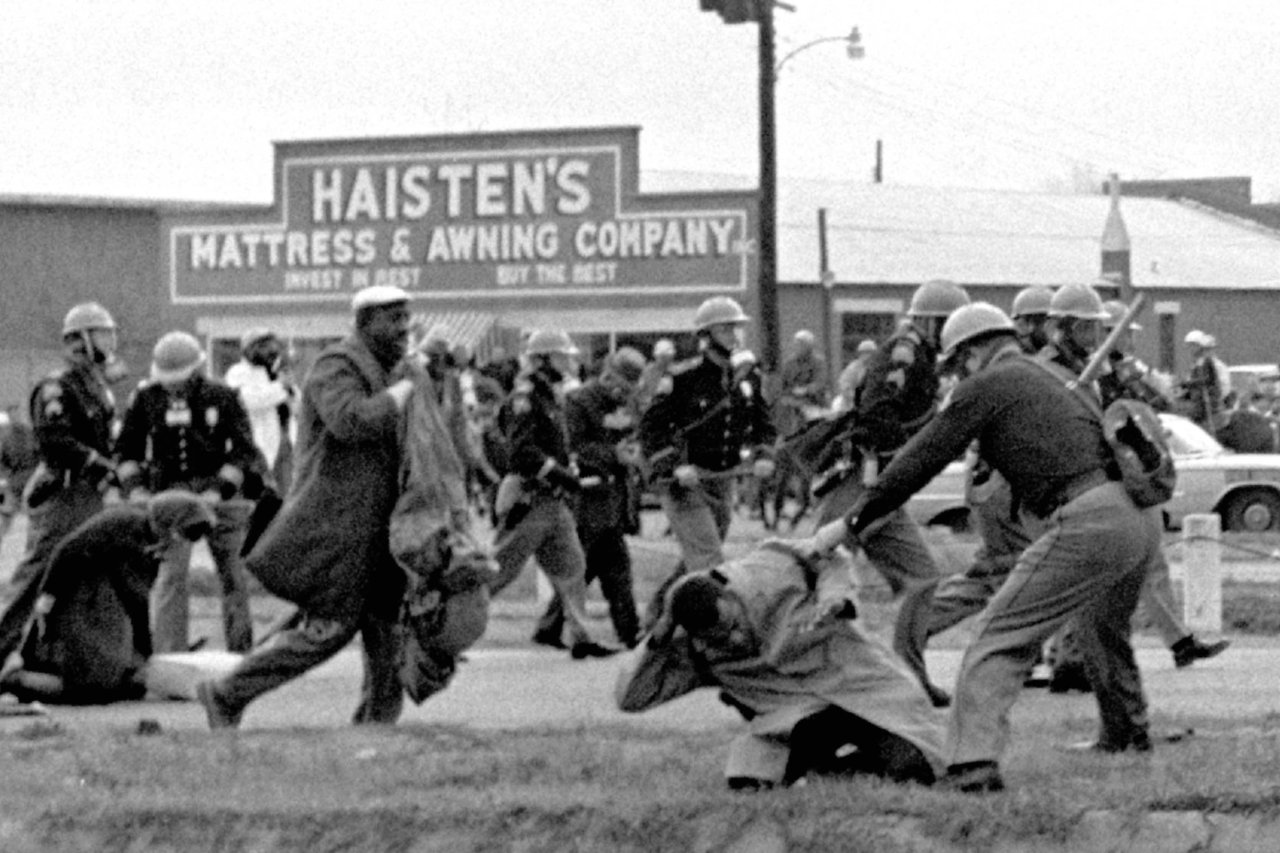

Selma, Ava DuVernay's film—a Best Picture Oscar nominee—tells the story of the events surrounding "Bloody Sunday" on March 7, 1965, when Alabama Governor George Wallace sent state troopers to attack civil rights protesters crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and the triumphant march from Selma to Montgomery that began on March 21 and ended March 25 with King speaking in front of 25,000 people at the state capitol.

DuVernay's movie has reminded audiences of the bravery and determination of King and civil rights leader (and later congressman) John Lewis, as well as of lesser-known local figures like Amelia Boynton Robinson, Annie Lee Cooper and the Reverend Frederick Reese. Walker, however, has been telling their stories daily for years, but with a unique perspective: When he tells visitors about Reese, Robinson and other members of the Courageous Eight—Dallas County Voters League members who met in secret after Alabama judge James Hare banned group meetings discussing civil rights—he is talking about people he has known nearly his entire life.

"Now I get to relive that history every day," says Walker, who is on the coordinating committee for the Bridge Crossing Jubilee, an annual four-day event the museum has held for more than 20 years. (President Barack Obama is expected to attend this year's 50th anniversary celebration, which runs March 5 through 9.)

On tours, Walker points to the metal basin in the museum's re-created cell and recalls the days he was locked up. "If they kept you less than 24 hours, the law required that they only give you water, so that's all they gave us." He also vividly recalls a day no arrests were made. On February 10, Sheriff Clark forced 160 students on a three-mile march out of town, his officers harassing them with clubs and cattle prods. "They were all right on top of you," Walker says. Clark's men backed off only when some older students picked up bricks and turned on them. "That was when we realized those people were cowards," he says.

The museum covers the entire struggle in Selma, but the Bloody Sunday stories stand out. Walker's parents kept him home that day (his father provided transportation for protesters, while his mother cooked meals for organizers at the church), but his brother Willie was there. "He got tear-gassed, and when he came in the house with his eyes all red, you could see the fear on his face," Walker remembers.

Walker believes the museum's greatest contribution has been in collecting the stories of everyday citizens, those even less known than Reese or Boynton Robinson, who was beaten unconscious on the bridge and who, at 103, attended Obama's State of the Union speech in January. One memorable oral history came from a white man who in 1965 had been a young trooper in Mobile for the Alabama Department of Public Safety. He was called to Selma that Sunday but was not briefed, simply handed a gas mask and riot gear. "In the moment he just followed what the other state troopers were doing," Walker says, "but he felt so badly afterward that he resigned a month later."

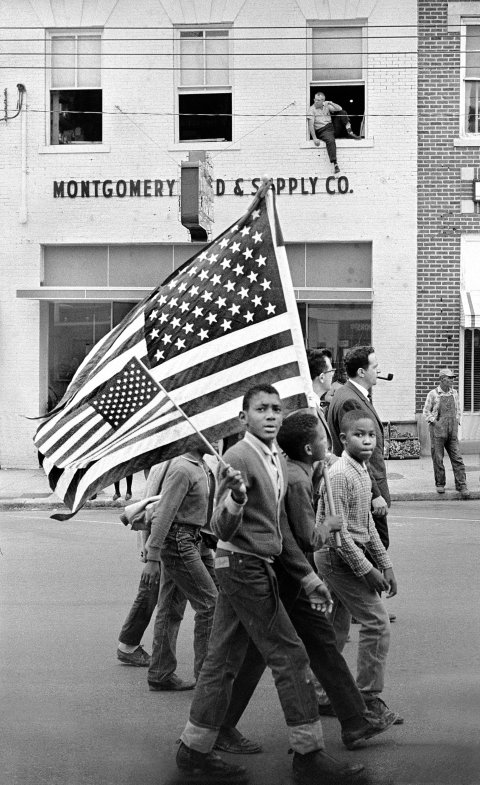

When King led the march to Montgomery on March 21, Willie Walker was in the vast crowd. Sam was there for the final four miles and heard the speeches. He spent the early days of the march cleaning up campsites after others had left so the local authorities would have no grounds for criticism. "It was a duty that you took pride in," Walker says.

Decades later, after a stint in the Army and a job in the California Department of Corrections, Walker again became a civil rights volunteer, although this time it was by accident. In 1992 he was injured in a car crash in California and came home to Selma to recover. Locals and civil rights veterans were starting a museum, and Walker, with time on his hands, pitched in. After the museum opened, however, a staffing problem nearly doomed it. "Everyone else had a full-time job," Walker says. "I said, 'It doesn't make sense to have a big grand opening and now the doors are locked.' They said, 'We don't have the money to pay you.' So I volunteered."

By the time his insurance settlement was paid out and he had fully recovered, he was an institution at this institution, so the museum found the money to make him an employee. When Walker, who handles about 80 percent of the museum tours, can't make it, Lawrence Huggins, his high school coach and physical education teacher, steps in. Now 79, Huggins also brings a unique personal perspective. When the students started marching in January 1965, most adults stayed away. Everything changed after January 22 when 105 local black teachers, led by Reese, put their jobs on the line and marched. Huggins was at the front of the line and took a baton to the stomach from one of Clark's men on the courthouse steps.

"The Teachers March brought a new dynamic to the movement," says Huggins. "More adults got involved after that."

Walker says Obama's election in 2008 drew new attention to the civil rights movement and the museum, adding that when the election night polls closed in Selma, locals marched across the bridge and said a prayer of remembrance "for all the people who had gone ahead of us and all the work they had done to make this possible."

Not surprisingly, he adds, DuVernay's movie has been a boon to the museum: "The day after the release we had huge crowds." And Walker's work has taken on a new urgency since the Supreme Court's 2013 decision to invalidate part of the Voting Rights Act, which allows the stripping away of vital protections earned with sweat and blood in 1965.

This year's Jubilee should draw tens of thousands to Selma. There will be bands, a street fair and a film festival, but Walker emphasizes that "this is an activist celebration. We'll be inviting people to join the movement, to do some real work."

Reese is hopeful that the Jubilee can persuade people in power to "step forward and make sure our rights and these memories are protected." The schedule includes workshops and panels on poverty, mass incarceration and, of course, voting rights; they'll be held in regional schools on Friday and for the general public over the weekend. "This time we need to expand our movement to try and elevate issues like economics, education and police brutality," Walker says. (Other events include a mock trial and a play about Jimmie Lee Jackson, the activist whose brutal murder in nearby Marion at the hands of law enforcement helped spark the Selma marches.)

That Sunday afternoon, everyone will march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. On Monday, those who are marching the 54 miles of highway to Montgomery will begin their long journey. "There's no question that this year's march is more important now that the Voting Rights Act is endangered," says Ralph Worrell of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. "We're putting a lot of emphasis on this campaign—it is as significant as it was in 1965."

Walker adds that the movement will not end with the march to Montgomery; the protections of the Voting Rights Act need to be restored with new legislation. "We have to continue to pound on Congress to take action," he says, prepared once again for a long journey.