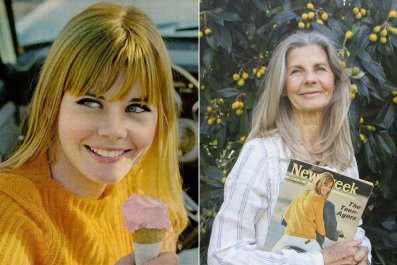

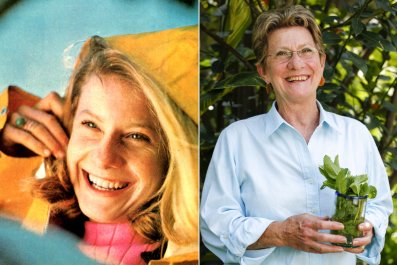

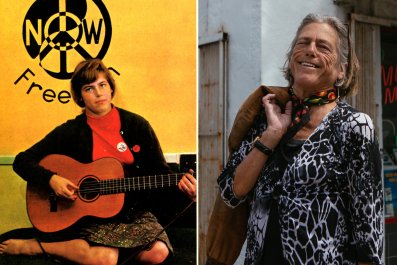

In 1966, Newsweek published a landmark cover story, "The Teen-Agers: A Newsweek Survey of What They're Really Like," investigating everything from politics and pop culture to teens' views on their parents, their future and the world. The article was based on an extensive survey of nearly 800 teens across the country, and it also profiled six teens in depth, including a black teen growing up in Chicago, a Malibu girl, and a farm boy in Iowa. Fifty years later, Newsweek set out to discover what's changed and what's stayed the same for American teens. The result, "The State of the American Teenager," offers fascinating and sometimes disturbing insights into a generation that's plugged in, politically aware, and optimistic about their futures, yet anxious about their country.

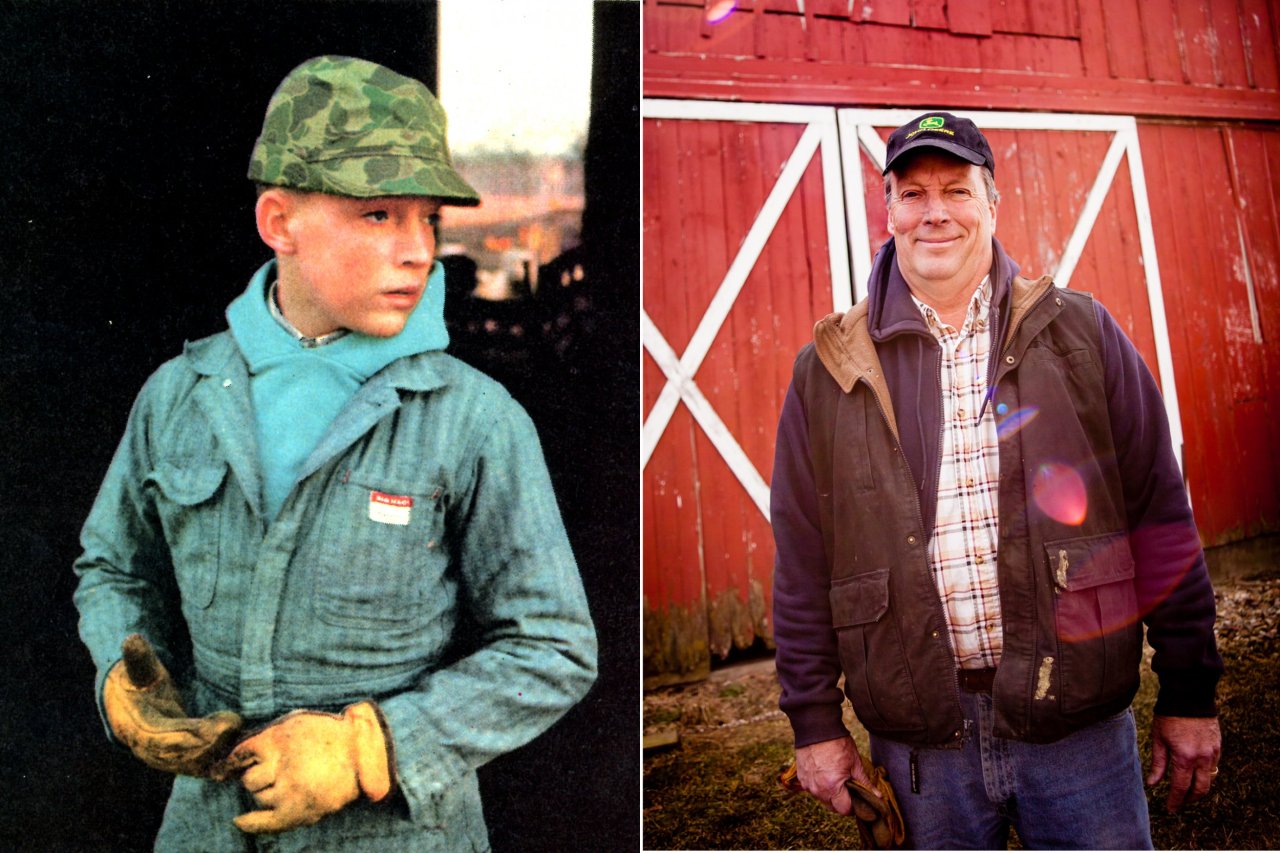

With pink cheeks and a tired, distant stare, 13-year-old Bruce Curtis stands in front of the barn on his father's 116-acre farm, a green Army cap pulled down to his brow. It's daybreak, and he's bundled up in blue coveralls and a teal sweatshirt, his hands covered by soiled yellow working gloves. "If you're looking at my picture in coveralls, you're thinking, That kid was never in New York!" Curtis, now 63, says of the photo Newsweek published in 1966. "But I used to live in Sparta, New Jersey, and ride the train to Penn Station and work in 11 Penn Plaza. I've come a long way from small-town Iowa."

Curtis grew up in Newton, Iowa, population 15,381 (today, it's 15,150). Every morning, he woke at 6 o'clock to feed his family's 30 cattle, 24 sheep, 12 rabbits, eight cats and one dog. After school, he plowed, hauled hay, fed the animals and put them to bed. His father was the plant process engineer for Maytag, and his mother died of ovarian cancer when Curtis was 10. "My father was very important in my life. He wanted me to be exposed to as many things as possible," he says, speaking with a slight twang. "I had a sense of wanting to learn about things beyond just the scope of being a farm boy."

Curtis's father had gone to Iowa State University, where he worked with professor John Vincent Atanasoff and graduate student Clifford Berry, who created the first electronic digital computer. He was also involved in the Manhattan Project at Iowa State, which developed and built the first atomic bomb. "He did a lot of things under the radar. It was very fortunate for me to see that."

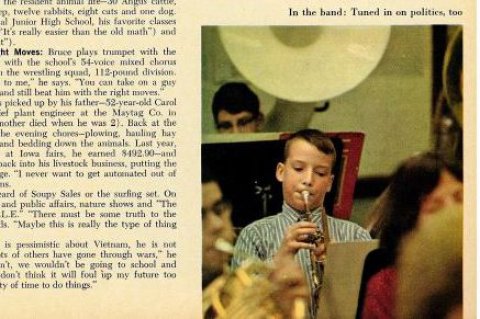

In 1966, Newsweek called Curtis's childhood "the vanishing rustic life—hunting, fishing, camping out and raising his own livestock," and he remembers his youth fondly, without regrets. He was involved in the Newton Rotary Club, played the trumpet in the school orchestra, joined the debate team and chorus, and became class president his senior year. He met his wife, Beverly, in high school; she worked at the local ice cream shop, the Kone Korner, which Curtis's uncle owned. "It will be 43 years this August," he says of their marriage. "That doesn't happen very often, does it?"

After high school, Curtis went to Iowa State, where he studied animal science and agriculture business. He'd wanted to become a veterinarian, but he says there were around 900 applicants the year he applied to Iowa State's College of Veterinary Medicine, and only 89 were accepted. He was not one of them. Instead, he's spent the last 42 years in the meatpacking industry, working for companies involved in slaughter and production all the way to the manufacturing and sales of fresh and processed meats. His wife and two sons followed Curtis in his many jobs to 11 cities, from Chicago and Cincinnati to Oklahoma City and New York. "I'm pleased with where my career has gone. It's tied to an industry that's part of my background. It's a very demanding business environment, and I've been successful from plant level to corporate to ownership of a company," he says. "I've experienced downsizing a couple times in that career, which gives you some humility and also gives you some strength."

In 1998, Curtis moved back to Newton, rebuilt the family farmhouse and now is a co-owner of Shelby Foods, which turns meat products into the raw materials for the meat, pet food and pharmaceutical industries across the U.S. and the world.

In the 1960s, Newton was the manufacturing muscle for Maytag. The company's headquarters, located in the tiny rural town, helped it flourish and employed thousands. All that changed in 2006, when the Whirlpool Corporation bought Maytag. The company closed a year later, taking with it many of the jobs that sustained the community.

Upper management—and the kinds of families that came along with it—disa ppeared from Newton, Curtis recalls. "It's a little more diverse [now]," he says. "It's a little more of a labor type of environment here. The school is smaller by population, so that has changed sports and academics." One positive addition has been the Des Moines Area Community College's Newton campus. "It's done a great job working with the school system to get high school students some of their further college credits. That is something we didn't have years ago," Curtis says.

Still, he worries about teenagers and the world they're inheriting. "I'm concerned about what college students will have for jobs. Terrorism for me is for sure a concern. We seem to have a world that's intent on destroying itself, and for me that's very unsettling," he says. Teenagers' greatest challenges, he thinks, will be self-confidence, employment and success. "You need to make things happen," he says. "It's not a given that there will be jobs for you. You have to go search it out."

When asked what advice he'd give young people today, he says, "That's a good question. Boy..." Then he goes silent. After a long pause, he says, "I was fortunate with the environment I grew up in and the family background, and some teenagers probably don't have that opportunity." He's also worried about drugs. When Curtis was in high school, he remembers some people drinking. "Today is scarier. You have scary things with meth and some of those things that really are ruining a lot of families and wrecking a lot of lives. It's a state problem. We're located along Interstate 35 and 80, and that drug traffic moves up [from the South]," he says. "Unfortunately, it is available. To be honest, I'm not sure I'd want to go through [being a teen] again."