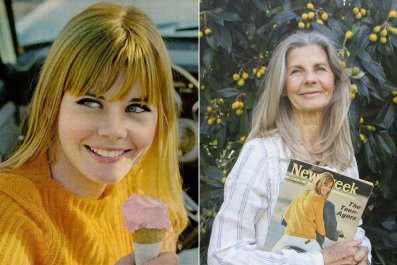

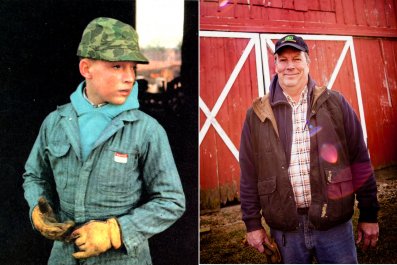

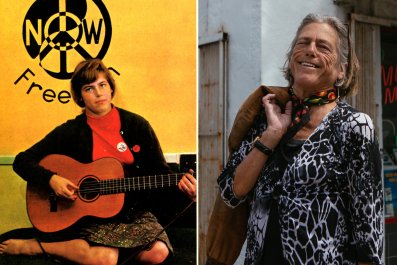

In 1966, Newsweek published a landmark cover story, "The Teen-Agers: A Newsweek Survey of What They're Really Like," investigating everything from politics and pop culture to teens' views on their parents, their future and the world. The article was based on an extensive survey of nearly 800 teens across the country, and it also profiled six teens in depth, including a black teen growing up in Chicago, a Malibu girl, and a farm boy in Iowa. Fifty years later, Newsweek set out to discover what's changed and what's stayed the same for American teens. The result, "The State of the American Teenager," offers fascinating and sometimes disturbing insights into a generation that's plugged in, politically aware, and optimistic about their futures, yet anxious about their country.

Christopher Reed was never one for labels. "I've always disdained the word teenager," he told Newsweek in 1966, when he was 17. He believed the word had "hostile connotations," and he referred to teens as they rather than we. "People think anyone who's a teenager is automatically a delinquent," he said. "I don't feel I'm a member of the vast portion of kids my age."

Growing up in a townhouse on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, Reed was a model of good behavior and an honors student at the elite Browning School near Park Avenue (graduates include John D. Rockefeller, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Jr., Jamie Dimon and Howard Dean). He rarely smoked. He avoided bars. He did his homework, practiced piano two hours a day. In his free time, he played hockey on the roof of his school and wandered through museums and galleries, and hoped for a girlfriend. His parents were divorced, he had two younger brothers; and every Saturday, he spent five hours at a rundown community center on the Lower East Side teaching children to read. Even at that age, he was sophisticated enough to understand life beyond his privileged bubble: "Everyone is always talking about the big problems of today's teenagers. But do they really have any? They have the same problems as older people—the world's problems."

After high school, Reed attended Harvard. "I went from one privileged boys school in Manhattan to an elite institution. I guess I've been living it down ever since," he says. When we imagine the futures of dutiful, privileged youngsters like Reed, we often think: lawyer, banker, hedge funder. But Reed wanted to make the world a better place.

His professional life has revolved around local farming, the environment, activism and education. "I've always been open to the idea that the most interesting changes happen on a small scale—grassroots. Institutions can do something that isn't top down, and that has real impact. So it's not a surprise that I would have landed in a small community that would easily be overlooked yet has its own contribution to make to changing the world."

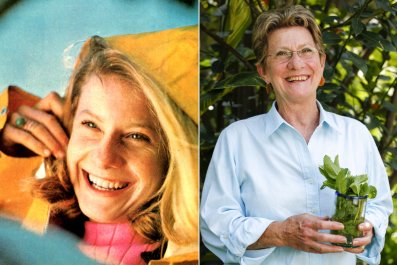

Reed, 67, lives in Philmont, New York, a village about two hours north of New York City. His longtime partner is an herbalist who founded High Falls Gardens, a small farm-turned-nonprofit dedicated to Chinese medicinal herbs. Reed is a community and environmental activist—he spent a lot of time protesting in Zuccotti Park during Occupy Wall Street, and in the early 20 00s, he helped wage a winning battle against a proposed cement plant in Philmont. Recently, he joined a local steering committee tasked with figuring out how to use the area's post-industrial infrastructure and history of water power to enhance the community. Reed jokes that he started working in the local food world "before it was fashionable" and, for the last 15 years, he's collaborated with small farms as a consultant and educator. He also worked as a woodworker and a contractor, and has taught piano for over 40 years.

"Because I rejected certain paths of success, I sometimes wondered if I was a failure," he says. "It's taken me a long time to know that there was a positive. That the things I chose to do did have meaning."

Reed looked up to his parents for their social intelligence (his mother was an artist and his father worked in insurance), and he admired his uncle, Henry Hope Reed, an esteemed historian and architecture critic, for his principles. "He said his elite education was worthless. Everything he learned, he learned on his own," Christopher says. "He had advice for me when I was a teenager that I still remember: 'See things as they are.' I think it takes courage to do that. Maybe it doesn't take as much courage if you're already under the gun economically. It's easier to see through the halo of illusions if you are suffering from tap water that's polluted, or have no way of surviving if you have a major illness because it's too expensive."

Reed doesn't have children but he's taught many young people over the years, and their fearlessness is what impresses him most, especially in the face of a future marked by student debt, fewer well-paying entry-level jobs, public health crises and wealth inequality. Asked what advice he'd give teens today, he says he'd tell them that "even the ugly truth is an important thing to pursue. Behind the ugly truth there are also beautiful truths about the resilience of people."

When reminded of his early aversion to the word teenager, he bursts out laughing. " I remember saying that, and I remember the flack I would get about that, too. Seeing people in aggregates and typing them is a very bad idea," he says. "I instinctively bristle now at these broad-stroke judgments, whether at Muslims or another embattled group. There's something going on to render those groups defenseless or vulnerable. Then they're condemned on top of that. That seems grossly unfair.…

"Life over a half-century is humbling. I hope that I'm cultivating more ability to empathize with different kinds of people. I'm still struggling to be more human. That's a lifelong challenge."