In the 20th century, chestnut blight and Dutch elm disease decimated billions of U.S. trees growing in forests and lining urban and suburban streets. The tree diseases, caused by invasive pests—a wind borne fungus spore from Japan and a beetle from the Netherlands, respectively—changed the face of one American city landscape after another and cost local governments and homeowners a fortune.

Today, 63 percent of U.S. forestland, or 825 million acres, is at risk of increased damage from established pests like the emerald ash borer, hemlock wooly adelgid and others, according to the U.S. Forest Service. Urban and suburban trees are the costliest casualties. Removal and replanting are expensive, and loss of trees from streets, yards and parks hurts property values and robs communities of the benefits trees provide, such as cooling and improved air quality.

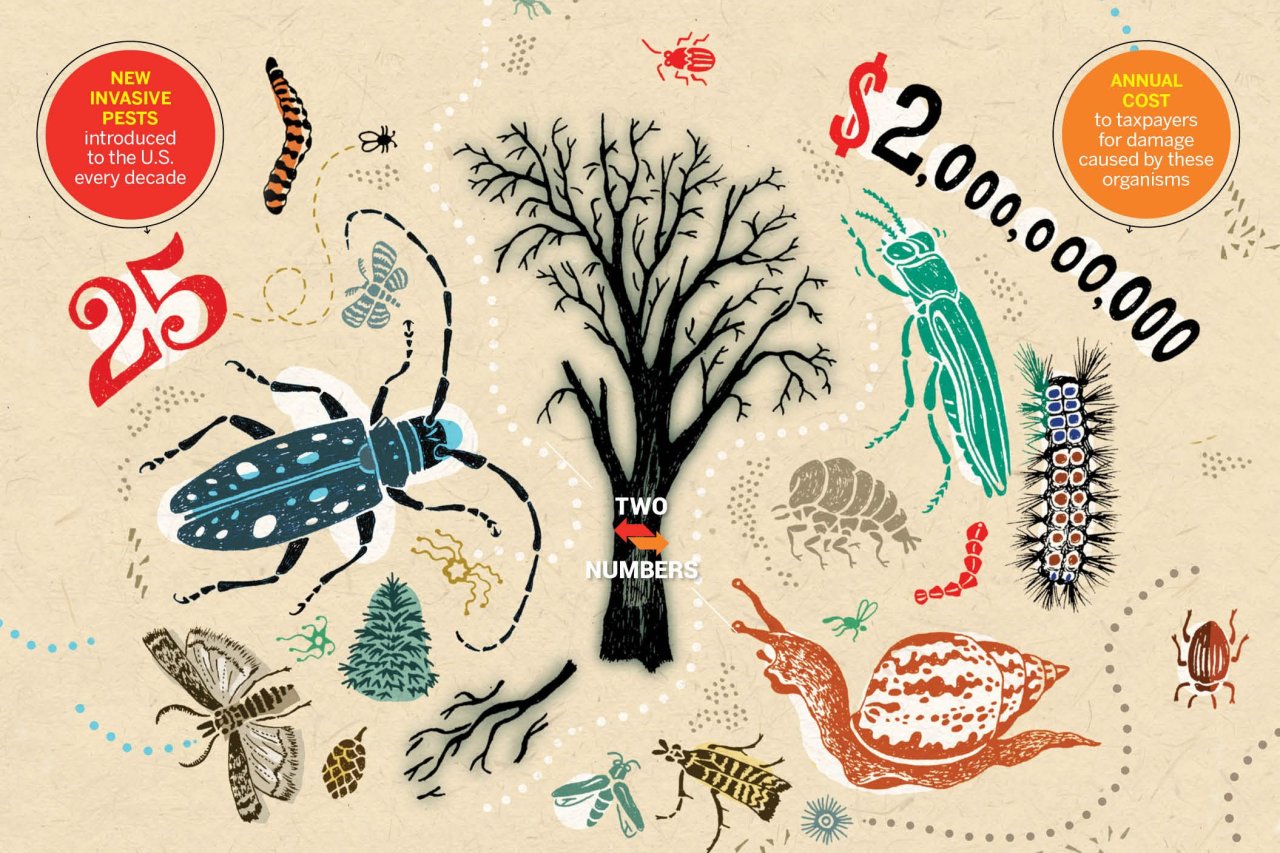

Those costs are not evenly distributed: Local governments tasked with tree removal and treatment pay 10 times more than the federal government does due to pest invasions. Homeowners who have to remove dead trees from their properties are stuck with $1 billion of the costs compared with the federal government's $216 million and the timber industry's $150 million burdens. That's apart from the effect on homeowner property values, estimated at $1.5 billion per year. In total, established tree pests are costing Americans well over $2 billion a year, according to a paper published May 10 in the journal Ecological Applications.

The problem is growing; the study calculates that 25 new pests enter the country every decade. The trend is due to escalating trade and increased reliance on shipping containers—these days, 25 million containers enter the U.S. each year. More than 90 percent of wood-boring insects that have recently invaded the U.S. entered on wood packaging materials mostly within these containers. And while the federal government requires that wood packaging material be treated to prevent pest importation and that plants be inspected upon entry to the U.S., there are too many shipments coming in each day to inspect everything.

"Current policies are helpful but not sufficient in face of this burgeoning global trade," says Gary Lovett, the study's lead author and a forest ecologist at the Millbrook, New York–based Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. Lovett and his coauthors say we need to phase out natural wood packing materials completely, and use alternatives like paper-based products. Packaging made of manufactured wood is another safer choice because pests are killed during the manufacturing process.

The stakes are already higher than most people realize. Forest pests are the only threat that can decimate an entire tree species within decades. We've been lucky, Lovett says, not to have yet encountered an imported pest destructive to the Southeast's loblolly pine or the Northwest's Douglas fir, two of the country's most commercially important trees.