Nancy Jo Sales has a special gift: the ability to talk—really talk—to teenagers. From New York City rap hipsters to the notorious, fame-obsessed teen burglars that Sales dubbed "the Bling Ring," the author and veteran journalist can get teenagers to open up about almost anything.

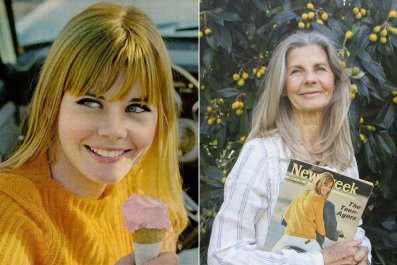

For her new book, American Girls: Social Media and the Secret Lives of Teenagers, Sales spent two years on the road listening to more than 200 teenage girls talk about what plagues them today. Sales, the mother of a high school freshman, has delivered a harrowing compendium of anecdotes about coming of age in an era of mainstream sexualization, slut shaming, online porn and cyberbullying. She spoke to Newsweek about why she wrote the book and what she learned about preparing teen girls—including her own—to grow up female online.

Where did you grow up, and what kind of a teenage life did you have?

I grew up in Miami in the 1970s. I loved my parents; my parents loved me. I went to a good public high school. I grew up in this unusually diverse atmosphere, all sexual orientations and all colors—people who followed gurus, hippies. It was good, but what I remember was that my mother always had this very strong sense of what was age-appropriate for children. I really was schooled in that concept from her: Certain things are OK at certain times. In that environment, you get exposed to a lot of things—people doing drugs, people who had flexible ideas of what was appropriate for young girls to be doing. My mother was very, very strict and protective of me. I would get mad and say, "But Mom!" [But] I had the best of both worlds: I was exposed to a lot of interesting stuff but also protected from things.

What is the biggest difference between female American teenage-hood in the 1970s and now?

Nobody is saying kids haven't always been interested in sex—we all were—but I think what's different is that access to pornography has changed how kids view sex in a big way. This is a huge, huge issue that should be the subject of a national conversation, and we are not having it. If you had asked me two years ago, "What do you think of porn?" I would have said, "Whatever, live and let live." I really have a different view now that I have looked at it. Gonzo porn is the most popular version, and it's very degrading to women.

We know from studies that porn influences girls' views of themselves and their bodies. This is a huge, huge change. The way this relates to social media is that online culture is influenced by this porn aesthetic—Tumblr is almost like a porn site. Also, iPhones.

My book is about porn-plus-iPhone. It is changing childhood and teenage life.

Are you sure you don't just feel the same generational difference that parents in the 1960s felt about their kids and free love, or their grandparents felt about making out in cars?

I hear that all the time. "Oh, it's always been that way, it's just moral panic." I am sorry, but there should be a word for the opposite impulse of moral panic—maybe there's a German word for it. It's denial. Sure, the car was once considered a dangerous thing because kids could drive off and neck. Well, now you can be doing an approximation of that in math class. You can be sexting at school, [watching] porn at school. It used to be that Saturday night, you might have an experience. Now it can happen all the time. It happens when you open your eyes in the morning and get sexted. The constancy of it—we can ask, Is it healthy? Girls complained to me about having to be on call all the time, like a doctor. These girls are constantly dinging.

You have a daughter. Do you monitor her social media life and phone?

I feel really lucky because when I started doing the first story on this for Vanity Fair , she was only 12 and didn't have a phone yet. I was able to learn about all these things and start having this ongoing conversation with her. We talk about this every day. She tells me about things that are going on in her peer group. It's something you have to talk to them about. Like, what happened in school today? What happened on social media today?

One of your strong suits is your ability to get teenagers to talk to you. What tips can you give less-communicative parents?

I don't really think of myself that way. I am a reporter, I need information, I push them like I would any source. As a parent, it's hard to remember; you feel this urge to protect. We are the supplicants now. We need information. We have to go to them with our hands outstretched: "Please help me here." Let them school you, rather than you school them.

My book is really not a parenting book. Many parents want so badly to be their child's friend that they don't discipline them. Kids really want rules and guidelines. The girls say, "Why do our parents let us do all these adult things?" I am not a parenting expert. I just asked the girls, "What do you think should be done?" A lot of the book is about problems that are deeper than parenting.

Will you talk about how social media affects consent and body image?

A lot of social media is posting provocative pictures. These girls are styling themselves to a porn aesthetic, and there are sexual comments. It's all about likes; it's all about the validation. The one thing that's different from when we were kids is there's a number on your popularity and everyone knows it. What gets a lot of likes is you in a bikini. And then so-called "slutpages" are in every school I went to [during reporting], and there's a sexting ring in every school. These are amateur porn sites. There's a whole minimizing thing that goes on, like, "It's just a prank." But it leads to terrible cyberbullying and sometimes suicide. The pictures are like Pokémon cards to the boys, who use them to jerk off or as a trophy.

This is a cultural phenomenon. What else can we call it? I began to see how deeply entrenched this is in the lives of teenage girls. I was not aware of it, and I felt so bad for them, that they were trying to deal with this. And the boys too, because "bro" culture is boy culture, and boys are overwhelmed. It's also really homophobic. It's not just sexist.

So what's the takeaway?

More than 200 girls in my book agree that there is a lot of harassment. They are pressured into sexualizing themselves; they are more vulnerable to cyberbullying. People need to know that these girls are concerned. More than half of the book is in their voices—it's one thing to hear an adult say it; it's another thing to hear a kid say it.

I think we have to change this culture. We cannot have a generation of girls growing up like this.

We have to have a conversation about porn—parents can't be afraid to say, "Nope, you are not doing that." Schools can institute sessions where kids can talk to each other about this, so it's not like an adult telling you what to think. It might be useful for sessions to be single-sex and then join them together. Some of the best conversations I had were when the girls started talking to each other. They said, "We never talk about this."

The law hasn't caught up to the technology. Girls are so vulnerable to having these pictures passed around. They know this is out there, and they have this incredible feeling of threat that has got to be addressed. Only a small percentage of boys will rape, but a lot more will press a button and send a picture. It's e-rape.