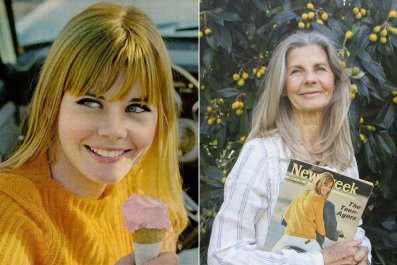

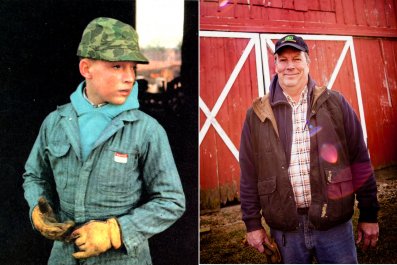

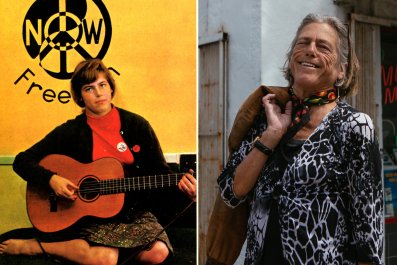

In 1966, Newsweek published a landmark cover story, "The Teen-Agers: A Newsweek Survey of What They're Really Like," investigating everything from politics and pop culture to teens' views on their parents, their future and the world. The article was based on an extensive survey of nearly 800 teens across the country, and it also profiled six teens in depth, including a black teen growing up in Chicago, a Malibu girl, and a farm boy in Iowa. Fifty years later, Newsweek set out to discover what's changed and what's stayed the same for American teens. The result, "The State of the American Teenager," offers fascinating and sometimes disturbing insights into a generation that's plugged in, politically aware, and optimistic about their futures, yet anxious about their country.

"I have been very nervous about this," Laura Jo Degan, 64, says at the outset of our phone interview. "I have to tell you the truth: I wasn't sure what ya'll wanted. I'm nothing.… I'm not.… My life is pretty ho-hum."

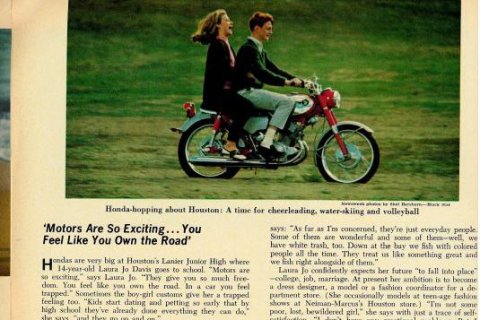

Fifty years ago, when Degan (who at the time went by her maiden name, Laura Jo Davis), spoke to Newsweek, she was a content 14-year-old. Growing up in Houston, she played volleyball, cheered, water-skied and rode horses. Once a week, she volunteered as a candy striper at a local hospital. Degan loved riding Honda motorbikes and worked hard in school (she cried when she didn't get an A or a B). Smoking, to her, was "repulsive," politics uninteresting and the Bomb not worth worrying about: "It's a stupid thought. I guess I feel it will never happen to me." She firmly believed her future would "fall into place." Her greatest concern in life? Boys.

Degan's seemingly unshakeable optimism—not to mention the cheerful photos Newsweek published of her gleefully riding a Honda motorbike and smiling brightly in a close-up—masked the hardships she'd endured.

The year before Newsweek's cover story, Degan's father, a photographer for Shell Oil, died of a heart attack on Mother's Day. "There were real traumatic things—I guess you can tell from my voice," she says, trembling. "Financially, that put a big strain on the family." Degan started working at a local florist, and her mother got a job running an OB-GYN medical center. Degan's brother and sister were older, so "it was just my mother and I, really, for a long time at the house."

And there was the bombing.

On September 15, 1959, Paul Orgeron, an ex-convict and tile-setter, walked into Poe Elementary School with his 7-year-old son, Dusty, and a briefcase jammed with dynamite. He wanted to enroll Dusty, but the principal told him they needed the boy's address and birth certificate. Orgeron vowed to return with the paperwork the next day. But instead of leaving, he took Dusty out to the playground and started blathering about God and power in front of about 50 students. Then he detonated the bomb hidden in his briefcase. Body parts flew everywhere. The blast killed six people: Orgeron, Dusty, the janitor, another teacher and two children. Seventeen more students were injured, including two who lost a leg, and the principal suffered a broken leg.

Degan was 8 years old, in her third grade classroom when the bomb exploded. At first she thought it was the Russians. Her teacher led everyone outside, but as an appointed school monitor, Degan had to run into the bathrooms and the teacher's lounge and shout "get out!" While her classmates exited the building with their teacher, who instructed them to look away from the carnage, Degan left by herself. "I came out, and because I wasn't told not to look, I looked," she says, sniffling. "Everything was in black and white, except for [the principal's] dress….That color of her dress was just so embedded in my brain. It was the most vivid purple."

Degan didn't talk about the bombing for many years, and then it was only with her family and best friend. "I was shattered," she says. "I couldn't sleep without the light on or somebody in my room. For a long time. We all got past it. They didn't send counselors into the schools in those days. You just sucked it up, and you went on to school."

When Degan graduated from high school, her mother "scraped up all the nickels and dollars we could find" and sent her on a trip to Europe. It was the summer of 1969. That fall, Degan started her freshman year at Louisiana State University. "I was convinced I could do anything with plants—cure diseases and stuff like that. I was going to be the mad scientist. That all went down the tubes because I realized you had to know a lot about chemistry." She studied landscape architecture instead.

Sophomore year, she was thrown from a horse and crushed her spine against a telephone pole. She didn't think she would ever walk again, or finish college, but she eventually did both, graduating from LSU seven years after she started. She was the first person in her family to earn a degree.

Degan, who came from five generations of Texans, moved back to Houston and worked as a landscape architect for 15 years. She and her husband married in 1980, when she was 30, and they have two children. She now works for his contracting business, but over the past 20 years she's spent most of her time taking care of three relatives with Alzheimer's disease. "When people ask me why I haven't been involved in my career—I'm a caregiver."

Degan's life has hardly been "ho-hum," but when she reflects back, her memories are tinged with a wistful hint of regret. "I guess I'm where I'm supposed to be. But with that in mind, I think I should have—how can I say?—I could have done more with my life. I think you always feel [that way] when you're reaching the end of life," she says. "I'm looking at retirement now, and that's pretty scary with the economy. So, I shoulda made a lot of money. That shoulda been my goal, but I never had those goals. I think my biggest goal was I wanted to be happy. I saw people who did not have a lot of joy. So I just want to be happy."

"Teenagers all have these really bizarre expectations that they're going to be Mark Zuckerberg," she says. "And then don't even get me started on Hollywood…. I choose not to look at that sort of thing. I'm sorry. I want to live the life of Mrs. Cleaver. Why can't it be like that?"