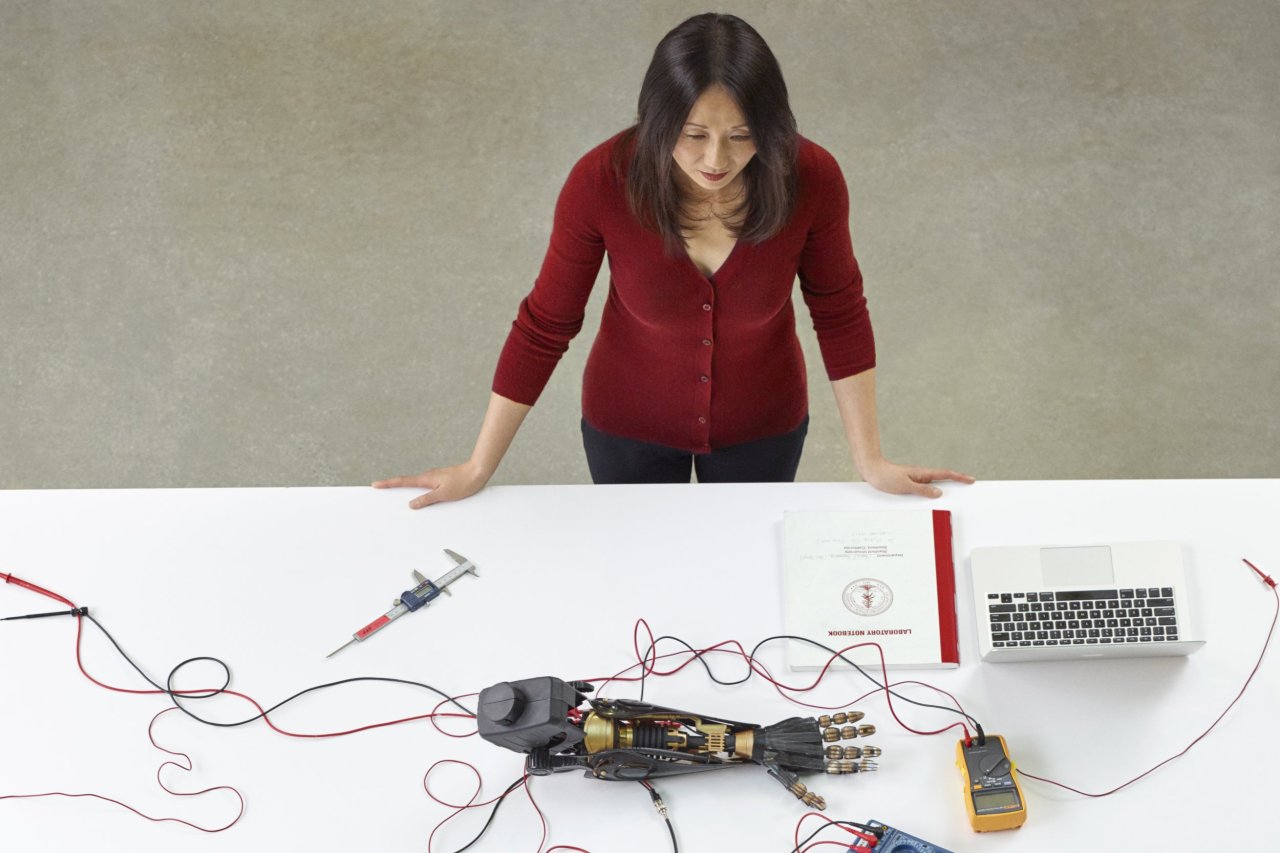

It's a good bet that in the not-too-distant future, most humans will be at least part cyborg, and Zhenan Bao, a professor of chemical engineering at Stanford University, wants to make sure she has skin in the game. Bao is working to develop an artificial epidermis that could improve the quality of life of amputees with prosthetic limbs and people with skin grafts, as well as make it more likely consumers won't have to take off their wearable fitness trackers.

RELATED: Breast cancer survivors trade scars for body art

"What we are trying to do is to come up with materials that can mimic the properties of human skin," says Bao. That includes making the synthetic skin stretchable, flexible, self-repairing and, eventually, biodegradable. The biggest challenge is to create a material that can feel. "When sensing touch, our skin will fire electrical pulses and send through the nerve system to our brain and allow our brain to understand whether it's pain or a hot object or cold object. Our electronic materials and devices also need to be able to do that." The skin she's testing is able to expand when heated, which lowers its electrical conduction and creates a way for the brain to "read" the temperature on the skin's surface.

She's tested out her skin on the brains of a few mice genetically modified so the area of their brain that typically transmits the sense of touch becomes ultra-sensitive to light. She connected her electric skin to the brains of the mice and saw that the brains responded when the electric skin was stimulated by bright light.

Bao, recently named a L'Oréal-UNESCO for Women in Science laureate, began work in flexible electronics some 20 years ago. She set out to make bendable smartphones and foldable televisions, but after arriving at Stanford 10 years ago, she realized her work had other applications, as well. She says companies such as Fitbit could use her electric skin to create more reliable personal devices. Once placed on the user's skin, the wearable could measure vital signs, such as tracking heart rate, blood pressure and blood sugar to monitor a person for heart attack or diabetes.

"Even though those sensors and the wearables exist, they are very large and bulky and uncomfortable to wear," she says. "So with the electronic materials we're developing, we hope to make them as thick as tattoos—but also have the same function."