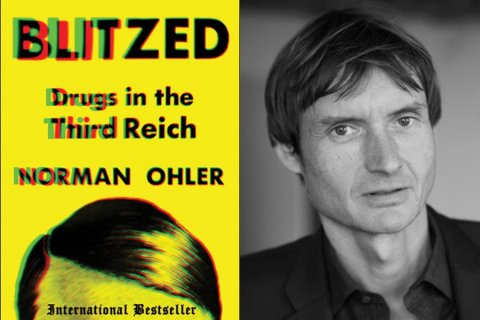

When Norman Ohler was just a kid, he and his grandfather were playing the board game Mensch ärgere Dich nicht, similar to Parcheesi. He and his classmates had just had one of their early-and-often lessons on the Third Reich, which perhaps even then included horrible footage filmed by American troops while liberating Buchenwald. Ohler wanted to know what his grandfather's role was in Nazi Germany. So he asked. His grandfather disappeared for a few moments into the yellow house he'd built after the war on the edge of the small town Ohler grew up in. He returned to hand Ohler an envelope containing his Nazi party membership booklet and a swastika pin. He didn't say much, and Ohler says he was too young to know what to make of this odd "inheritance."

But he was aware that sometimes, when there was a problem in the democratic West Germany of the 1980s, his maternal grandfather would say that "under Hitler, this never would have happened," or that "under Hitler, everything was in order." Ohler's grandfather portrayed the Nazis as "clean-cut." Ohler would later discover that many Nazis, including Adolf Hitler, weren't as clean-cut as his grandfather remembered.

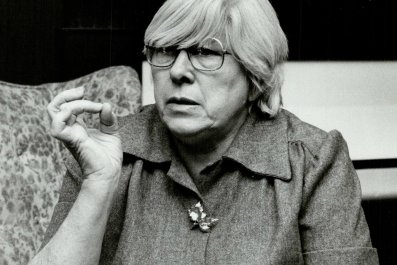

His most recent book was released in the U.S. on Tuesday with the title Blitzed: Drugs in the Third Reich and translation by Shaun Whiteside. It was a bestseller in its native Germany—published under the title Der totale Rausch (The total intoxication) in September 2015—and a Guardian Bookshop best-seller in the U.K. Publication rights for the work have been sold to 26 countries outside Germany, including Brazil, China, Israel, Japan and several in Europe. Ohler's first nonfiction book argues—in more than two dozen different languages—that under the Nazi regime, German civilians were high, their soldiers were high, and their führer was high.

Becoming a Writer

Ohler started becoming a writer as a young man thanks indirectly to his grandfather, he tells Newsweek, sitting in front of a webcam in his apartment in Berlin for a Skype call. It turned out that his grandfather had been a railway engineer. "At one point during the war, he had been working in a small but not unimportant railway station in the east in occupied Czechoslovakia," Ohler explains. There was a story his grandfather told him about the time he saw a train full of Jewish prisoners en route to the nearby Theresienstadt concentration camp. "He saw this train, and he decided not to do anything," Ohler says. "He said he was afraid of what would happen to him because the SS was guarding this train. Even though he realized that there was something wrong... As he said, this was against the regulations concerning the German railway system, to keep prisoners like that in...a cattle train." That's how Ohler learned his grandfather "didn't actively send people to death, but he was, you could say, like a wheel in the system. And certainly not in the resistance or not doing anything against it to stop it."

His grandfather's nostalgia for the "order" of Germany's darkest era—which Ohler says was common in 1980s West Germany—made him angry. As a teenager, he began hating Germany. He adopted leftist views and "looked for ways to resist right-wing developments," he says. "[There's] a slogan we have in Germany. It's also a cliché in a way too, but it's like, we have to do everything we can so that something like this doesn't happen again." He decided that what he could do was to become a writer and journalist "to uncover bad things in society and help the democratic process."

Ohler started spending less time playing tennis and more time immersed in politics and literature. He took courses in philosophy and cultural sciences at Humboldt University in Berlin and attended the Hamburg School of Journalism, publishing stories in German magazines such as Der Spiegel and Die Zeit. Today, he identifies as a novelist. He wrote Die Quotenmaschine (The quota machine), a hypertext novel about a mute detective, when he moved to New York in 1993; Mitte (Center) about ghosts and gentrification, when he was back in Berlin; and then Stadt des Goldes, published in translation as Ponte City, when he spent time in Johannesburg. He's also written for film and spent time in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem and Ramallah, where he interviewed Yasser Arafat about a month before the Palestinian leader's death.

"It's kind of a coincidence that I would actually come back to write about the so-called Third Reich," he says, before demurring. "Or maybe it wasn't at all." He'd once begun writing a novella inspired by his relationship with his grandfather, but abandoned the project. Nazi Germany, he admits, "is hard to write something about."

Discovering Drugs

Blitzed almost became Ohler's fourth novel. He stumbled on the topic of drugs in Nazi Germany through his connection to Berlin's thriving music scene and its connection to illicit substances. His friend, the DJ Alex Krämer, is a "pretty crazy guy. And a history buff too. And a drug buff. He really knows his drugs," says Ohler, who has not been shy about sharing with the press that he too experimented with drugs in his 20s. Krämer told him that Nazis took "loads of drugs" and recounted a story about some folks he met who had broken into a pharmacy in a former East German neighborhood and found an old stash of Pervitin, methamphetamine pills popular during Nazi times. When Krämer tried them, he got really high. "Then he realized that back in the Nazi days, people were actually using strong drugs." They were "pure and potent."

Ohler started developing characters and visiting archives so he could get the underlying facts about Nazi drug use right. "But what I found in the archives made me change my mind about the genre of the book I wanted to write," he says. "Because I thought this material is too," he pauses, searching for the right description, "brisant, as we say in German, is too hot to water it down in a fictional work." The word he struggled to find translates literally as "explosive," and in that sense, his book doesn't disappoint. Mix Nazis and drugs, and the result is brisant. Boom.

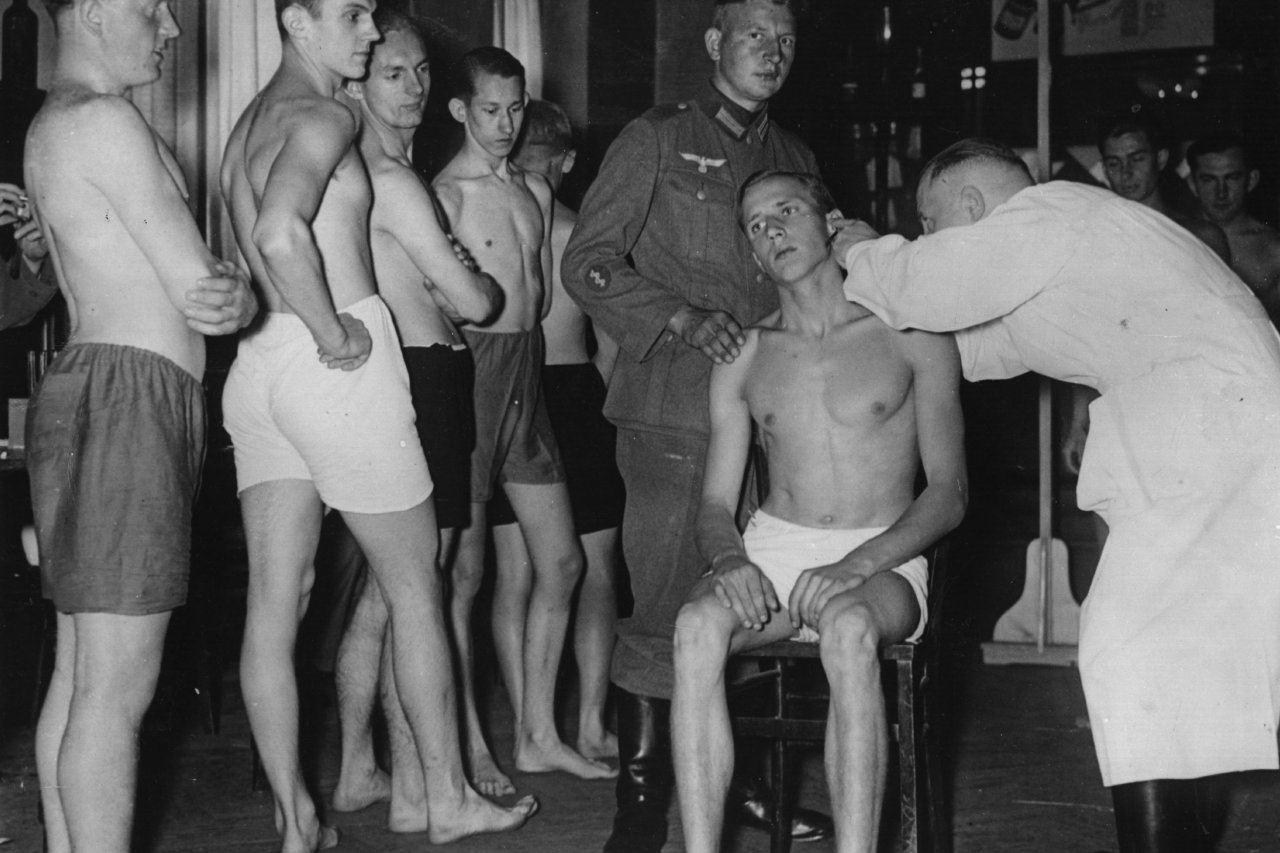

With guidance from well-known German historian Hans Mommsen (who has since passed away), Ohler continued his research, interviewing experts and visiting archives in Berlin, Koblenz, Munich, Sachsenhausen, Dachau, Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. He wanted to write about all aspects of drug use and incorporates into Blitzed sections on the history of pharmaceutical development in Germany back to the 1800s, the experimentation and excesses of the interwar Weimar Republic, the prevalence of Pervitin in German society after the drug was introduced into the market, research on and consumption of the drug in the context of the newly rearmed military, the importance of meth in keeping troops awake and energized during the early blitzkriegs, and the frantic efforts to invent a wonder drug as defeat became inevitable, including an experiment by the navy that had concentration camp prisoners march for hours on end to test the effects of new concoctions.

The longest chunk of the book focuses on Hitler and his relationship with Theodor Morell, who was appointed by the dictator as his personal physician in 1936 and accompanied him ever more closely almost until the end of his life. Morell, the rotund, balding man whom Ohler calls "the fat doctor," began by injecting Hitler with various vitamins, but in time added animal hormones and finally stronger substances, including a drug called Eukodal, whose active ingredient is the opioid oxycodone, Ohler explains. He describes another doctor who visited after Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg tried to assassinate Hitler with an exploding briefcase in 1944 and treated his burst eardrums with cocaine.

Ohler relishes the contradictions in his story, like the dissonance between the image of Hitler as a health-conscious teetotaler who worked indefatigably on behalf of his nation and the "bent, halting figure" he became, one a visitor described as "pale" with "unkempt" hair and "withered skin." He's fascinated by the image of "clean-cut" Nazis his grandfather went on about in stark contrast to a reality in which drugs helped fuel the war effort.

He describes the "strict, ideologically underpinned anti-drug policy with propagandistic pomp and draconian punishments" as "a vehicle for the exclusion and suppression, even the destruction, of marginal groups and minorities." The Nazis drug policies, he argues, were deeply linked to anti-Semitism. Their "war on drugs," he tells Newsweek, is a "highly problematic concept" that didn't disappear with the Third Reich, pointing to the image of African immigrants in more recent years in Germany and to U.S. "war on drugs" policies that disproportionately targeted African-Americans. Having watched Ava DuVernay's Oscar-nominated documentary 13th midway through reading Blitzed, Ohler's comparison felt relevant. The parallels are not exact but are nevertheless difficult to ignore.

Fact and Fiction

The book's jacket proudly sports praise from Ian Kershaw—a British historian focusing on 20th-century Germany and a prominent biographer of Adolf Hitler—who called Blitzed "very good and extremely interesting...a serious piece of scholarship, very well researched."

But other historians took issue with Ohler's methods and conclusions. Nikolaus Wachsmann, a professor of history at Birkbeck College, University of London, and author of KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps, started out with a gentle critique in his piece for the Financial Times, saying Ohler "overstates his case," and then got more severe, saying Ohler "[eschews] nuance for headlines" and "appears to mix fact and fiction." He ended his assessment harshly, saying that Ohler's "diligent research...is buried beneath the breathless prose," and poking fun at his writing style by asking whether Anglophone readers will "experience a big buzz, or a bad trip?"

Likewise, Richard J. Evans, historian and author, most recently, of The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815-1914, wrote in a piece for The Guardian that Ohler makes "sweeping generalizations" that are "wildly implausible," pointing to comments like one about the "doping mentality [that] spread into every corner of the Reich." Though he too conceded that the author "diligently researched in the German federal archives and other relevant collections," he called the book "crass" and "morally and politically dangerous," interpreting it as relieving Hitler and his supporters of ultimate responsibility for their actions.

Ohler points out a few careless inaccuracies in the review—Evans mentions, for example, "the Führer's...continual methamphetamine abuse," even though Ohler writes that Hitler only used that particular substance once. He insists that his work is not meant to excuse leaders of and participants in the "most horrible crimes committed by mankind," or to replace any other narratives of that time, only a chance to "read through whole narrative again from the crazy drug angle." In a passage that Evans views as a perfunctory "disclaimer," Ohler concludes that Hitler "remained sane until the end" and was "fully in command of himself: this was the true Hitler." The drug consumption, he writes, "does not diminish his monstrous guilt." He tells Newsweek, "It would be a different picture if Hitler would have been a sane, rational, good-hearted leader and through the drugs became a crazy man that killed millions of people. That's obviously not the case."

What Wachsmann snidely called "breathless prose" is Ohler's attempt to reach a broad audience. He says that he had read German history books that were "horribly boring," and wanted to bring his sensibilities as a novelist to the task. "I tried to combine academic research with the style of writing that I appreciate," he says. "I really didn't want to write a boring book."

He didn't, though some of his precision and personality seem to have been lost in the English translation. Still, his goal came with obstacles. "It's kind of a tightrope walk sometimes. Because through a very fluid style you might convince readers of a certain argument and probably in a nonfiction book you have to really stick to the material," Ohler says. "In a way, I think every nonfiction book is fiction," he adds. "You always wander off from the material you have, and you create a narrative." He writes about his perspective on nonfiction in a preface that was omitted from the English-language edition, depriving readers of a grain of salt Ohler originally offered. Blitzed is rooted in fact. The spot where he took the most "creative license," Ohler says, is when he allowed himself to assume Hermann Göring, a regular user of morphine, was in fact high during a specific conversation with Hitler about Dunkirk. Precisely how much more "wandering off" Ohler did isn't clear, but even accounting for some hyperbole, the book achieves something nearly impossible: It makes readers look at this well-trodden period in a new way and does it in a readable, inviting format. It also doesn't preclude future scholarship by professional historians to elaborate on the role of drugs in Nazi Germany.

Ohler's grandfather probably wouldn't have liked the counter-narrative to his memories of "order" under Hitler, but for a grandson who rebelled against that kind of thinking, it was "quite thrilling."