In a room at the United Nations overlooking New York's East River, at a table as long as a tennis court, around 70 of the best minds in artificial intelligence recently ate a sea bass dinner and could not, for the life of them, agree on the coming impact of AI and robots.

This is perhaps the most vexing challenge of AI. There's a great deal of agreement around the notion that humans are creating a genie unlike any that's poofed out of a bottle so far—yet no consensus on what that genie will ultimately do for us. Or to us.

Will AI robots gobble all our jobs and render us their pets? Tesla CEO Elon Musk, perhaps the most admired entrepreneur of the decade, thinks so. He just announced his new company, Neuralink, which will explore adding AI-programmed chips to human brains so people don't become little more than pesky annoyances to new generations of thinking machines.

RELATED: How a 94-year-old genious may save the planet

A few days before that U.N. meeting, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin waved away worries that AI-driven robots will steal our work and pride. "It's not even on our radar screen," he told the press. When asked when we'll feel the intellectual heat from robots, he answered: "Fifty to 100 more years."

Forecasting the Future

At the U.N. forum, organized by AI investor Mark Minevich to generate discussions that might help world leaders plan for AI, Chetan Dube, CEO of IPsoft, stood and said AI will have 10 times the impact of any technology in history in one-fifth the time. He threw around figures in the hundreds of trillions of dollars when talking about AI's effect on the global economy. The gathered AI chiefs from companies such as Facebook, Google, IBM, Airbnb and Samsung nodded their heads.

Is such lightning change good? Who knows? Even IPsoft's stated mission sounds like a double-edged ax. The company's website says it wants "to power the world with intelligent systems, eliminate routine work and free human talent to focus on creating value through innovation." That no doubt sounds awesome to a CEO. To a huge chunk of the population, though, it could come across as happy-speak for a pink slip. Apparently, if you're getting paid a regular wage to do "routine work," you're about to get "freed" from that tedious job of yours, and then you had better "innovate" if you want to, you know, "eat."

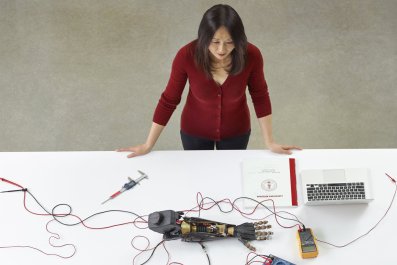

The folks from IBM talked about how its Watson AI will help doctors sift through much more information when diagnosing patients, and it will constantly learn from all the data, so its thinking will improve. But won't the AI start to do a better job than doctors and make the humans unnecessary? No, of course not, the IBMers said. The AI will improve the doctors, so they can help us all be healthier.

Hedge fund guys said robot trading systems will make better investing decisions faster, improving returns. They didn't seem too worried about their careers, even though some hedge funds guided solely by AI are already outperforming human hedge fund managers. Yann LeCun, Facebook's AI chief and one of the most respected AI practitioners, says AI will be used to discover and help eliminate biases and bring people together—yet for now, AI gets accused of uncovering our individual biases and serving up content that confirms and hardens them, thereby making half the country mad at the other half.

Grete Faremo, executive director of the United Nations Office for Project Services, beseeched technologists to slow down a bit and make sure the stuff they're inventing solves the world's great problems without making new ones. But another speaker, Ullas Naik of Streamlined Ventures, hinted at how quantum computing will soon greatly speed up development of thinking machines. He believes quantum computing is closer than most people think, and in case you don't know, a quantum computer will be so freakishly powerful, it will make any computer today seem as old-fashioned as an Amish buggy.

Put all this together, and AI might be the most wonderful technology we've yet created, helping humans get to a higher plane—if it doesn't turn against humans, Terminator style. Though most likely, it will land somewhere in between.

Same Old Innovation?

Here's a question worth considering: Is this AI tsunami really that different from the changes we've already weathered? Every generation has felt that technology was changing too much too fast. It's not always possible to calibrate what we're going through while we're going through it.

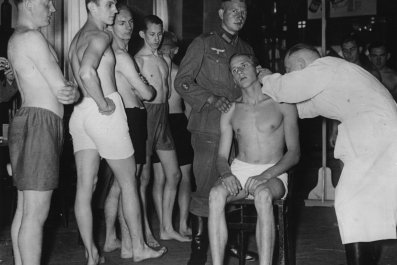

In January 1965, Newsweek ran a cover story titled "The Challenge of Automation." It talked about automation killing jobs. In those days, "automation" often meant electro-mechanical contraptions on the order of your home dishwasher, or in some cases the era's newfangled machines called computers. "In New York City alone," the story said, "because of automatic elevators, there are 5,000 fewer elevator operators than there were in 1960." Tragic in the day, maybe, but somehow society has managed without those elevator operators.

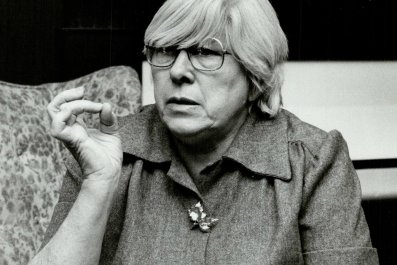

That 1965 story asked what effect the elimination of jobs would have on society. "Social thinkers also speak of man's 'need to work' for his own well-being, and some even suggest that uncertainty over jobs can lead to more illness, real or imagined." Sounds like the same discussion we're having today about paying everyone a universal basic income so we can get by in a post-job economy, and whether we'd go nuts without the sense of purpose work provides.

Just like now, back then no one knew how automation was going to turn out. "If America can adjust to this change, it will indeed become a place where the livin' is easy—with abundance for all and such space-age gadgetry as portable translators…and home phone-computer tie-ins that allow a housewife to shop, pay bills and bank without ever leaving her home." The experts of the day got the technology right, but whiffed on the "livin' is easy" part.

So for every pronouncement that AI is different—that the changes it will drive are coming at us faster and harder than anything in history—it's also worth wondering if we're seeing a rerun. For all we know, 50 years ago a group of technologists might have got together at the U.N. and expressed pretty much the same hopes and concerns as the AI group.

Except that was 1965. They would've talked over tuna casserole. At least the sea bass served at the U.N. confab represents progress.