On November 18, 2001, astronomy student Lena Okajima was braving frigid temperatures in the mountains close to Tokyo. It was her first time witnessing the annual Leonid meteor shower, and what she saw that night—thousands of shooting stars streaking across the clear winter sky—captivated her, charting her path for the next decade.

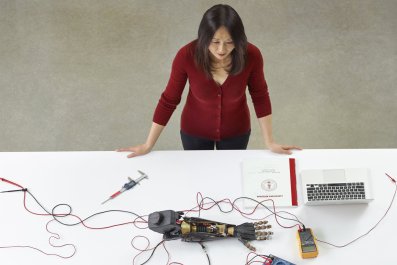

In 2011, she founded Ale Co., which is dedicated to bringing artificial shooting stars to the masses. "There are a lot of people who enjoy seeing shooting stars, but often you have to go up in the mountains and freeze yourself to actually see anything," says Rie Yamamoto, Ale's global strategy director. "With our stars, you'll be able to go to a restaurant or rooftop bar and enjoy it with a beer in hand."

"We want to create a new culture of enjoying shooting stars," says Okajima, who through her ambitious Sky Canvas Project aims to hold the world's first artificial meteor show, in early 2019. The "stars" will come in an array of different colors, burn brighter and last up to 10 times longer (close to three seconds), as compared with naturally produced shooting stars.

To create the artificial shooting stars, Ale will launch a microsatellite into orbit early next year, approximately 310 miles above Earth. The company has secured a spot on a rocket to carry the payload into space, but it cannot reveal additional details because it has signed a nondisclosure agreement. The satellite will contain up to 300 marble-sized pellets, which when released will fall toward Earth, burning up in the atmosphere to produce a dazzling display of light visible across distances of over 120 miles on the ground. The pellets are made from various elements such as lithium, potassium and copper, says Okajima, and varying their composition can result in stars of different colors.

While the concept has never been tested, aerospace engineer Hugh Lewis of England's University of Southampton says it's a feasible idea, "based on pretty well understood physics. The key challenge will be to release [the pellets] at the right altitude and the right time, because it's very, very difficult to predict the timing of re-entry and at what point they'll start to burn up."

It's a task that Okajima and her team have been tackling for the past six months, with some success. She says they're now able to discharge pellets at the desired speed and angle—factors crucial to precise re-entry—within an accuracy of 1 percent of target values.

However, Lewis is worried about introducing additional objects into Earth's already cluttered orbit. "It's not a sustainable activity that you would want to encourage just for amusement."

Okajima says her project will not just entertain but also contribute to greater scientific understanding of what the Earth's upper atmosphere is like and how objects such as decommissioned satellites can safely re-enter it.

Still, Ale's main focus is to "paint the night sky with shooting stars." Its debut show is slated for early 2019 in Hiroshima. If all goes well, the company hopes to bid for a place to "perform" in the opening or closing ceremony of Tokyo's 2020 Olympics.

"For now, space development is for governments, big companies or the superrich," says Okajima. "But we hope our shooting stars can be enjoyed by everyone."