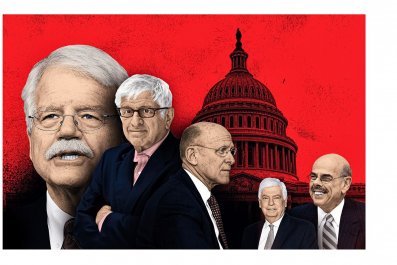

When Martin Shkreli, former CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, raised the price of Daraprim, which treats dangerous infections, from $13.50 to $750, the public was appalled.

But lost in the outrage over predatory pricing was one crucial fact: What Shkreli did was completely legal—and common. Between 2012 and 2017, for example, the price for Nitrostat, which prevents and treats chest pain, increased by 477 percent, from $15.91 to $91.76. Nothing about the medication changed during those years—not its chemical formula, not its uses and not the manufacturing process. Pfizer, which sells Nitrostat, offered no explanation for the spike.

In fact, according to a report published in March by the minority staff of the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, prices for the top 20 drugs prescribed to older Americans rose by an average of 12 percent annually during this five-year span. For seven of these drugs, the total increase was more than 100 percent. Such spikes don't necessarily translate into customers paying more at the pharmacy, but experts in health care economics say they do raise frustrating questions about the future of Medicare and prescription drugs in general. Most frustrating of all may be how impossible they are to answer.

Older Americans spend a big portion of their income on prescription medications. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 91 percent of people over age 65 take at least one drug, and one in four has difficulty paying for them. But seniors aren't alone. In 2016, Americans spent nearly $330 billion on prescriptions, about $1,000 for every citizen.

Raising the price of a brand-name drug during the life of its patent is a standard practice in the pharmaceutical industry. And the reason behind it, says Darius Lakdawalla, director of research at the Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at the University of Southern California, is well documented. Patients who take a newly approved drug are potential long-term customers, and the manufacturer wants their loyalty. "Drug companies have an incentive to price lower early in the patent cycle, then steadily increase the price over time," says Lakdawalla. The hikes continue until the so-called patent cliff, when the drug goes generic and the price plunges.

New drugs are usually priced higher than their competitors, presumably because they're better than what is already out there. But these days, something strange is happening: When a medication enters the market, companies reprice already-approved competitors to match it, even if they've been available for years.

Lakdawalla suggests a few possible explanations. The rise of pharmacy benefit managers—companies that act as middlemen, negotiating for lower prices on behalf of insurers—may be creating pressure for old drugs to keep pace, thereby earning themselves money through rebates and sales. These increasingly powerful players in the supply chain have an incentive to work with the highest-priced drugs because they come with the biggest rebates. Older, lower-priced drugs offer a smaller rebate, which makes the middlemen less interested in them. The only way to remain a player in the market is to offer the same rebate to the pharmacy benefit managers, which means raising the list price.

Alternatively, says Lakdawalla, the absence of market pressures could be creating less competition among similar products. So instead of jockeying for first place by virtue of a lower price tag, all drugs for a certain condition raise their price in concert. Many companies don't have any truly innovative drugs at the moment, so they're trying to squeeze every possible penny from patents. Lakdawalla also says the increasing cost of launching a new drug probably pushes prices up.

Other analysts point toward a simpler explanation: Companies demand more simply because they can. "Prices are set at whatever the market will bear," says Aaron Kesselheim, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard's Brigham and Women's Hospital. "That's the fundamental principle behind drug pricing in the U.S."

Pharmaceutical companies say that the increases are justified and that patients won't be denied access on account of the cost. "Our decision to change prices can be based on a range of considerations, reflecting competitive and market dynamics," says Pfizer spokesman Thomas Biegi.

Sanofi-Aventis, which makes Lantus and Lantus Solostar, both among those top seven drugs in the committee's report, insists its pricing strategies decrease patient copays and discounts for Medicare beneficiaries. And in a 2016 blog post, Brent Saunders, the CEO of Allergan, which makes Restasis—priced at $167.62 in 2012 and $321.26 in 2017, according to the committee's report—vowed to avoid predatory pricing practices. "We will take price increases no more than once per year," he wrote, "and, when we do, they will be limited to single-digit percentage increases."

Individual Medicare beneficiaries aren't the only concern, says Juliette Cubanski, associate director of the program on Medicare policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation. All medications, she says, not just those used by seniors, are subject to the rising price trend, and all taxpayers pay for Medicare. Sooner or later, the high price of a prescription drug will lead to a public health crisis. When, say, a cure for Alzheimer's disease comes along, the treatment will likely be too expensive for all those in need. "How do we decide who should get it?" she asks. "And who should pay for it?"

It's unclear how the country can avoid this looming crisis. Granting Medicare the power to negotiate drug prices—currently forbidden by federal law—might help, says Cubanski. Seniors enrolled in Medicare can choose from a large number of private plans that are free to negotiate with drug companies. Keeping the federal government out of those deals creates competition among the individual plans, which drives health care costs down. But as the single biggest insurer in the country, many experts say, Medicare could force companies to lower their prices.

Political muster to change Medicare's design, however, has been weak. President Donald Trump's proposed budget for 2019 includes no mention of this change alongside other methods for reducing drug costs. And although Trump railed against high drug prices at the start of his presidency, that talk ended in March with a closed-door meeting with several Big Pharma CEOs. The president maintains he's still committed to pushing for Medicare to have negotiating power, but any bill will likely face political pushback. "Republicans have historically opposed allowing Medicare to negotiate," says Cubanski.

Even if Medicare had such leverage, a congressional study calculated the benefit as slight at best. A better approach, says Kesselheim, would be to grant Medicare, or any insurer, the power to exclude drugs from the list of medications it covers. He cites the Department of Veterans Affairs as an example of how effective the threat of omission can be: The VA health system obtains the best drug prices among all government insurers.

Guaranteeing that doctors are educated about new drugs by neutral parties with no financial stake—not, in other words, a pharma representative—might also help. As would forced transparency. California recently passed legislation requiring drug companies to disclose any price increase of 10 percent or higher. "This may not lower out-of-pocket costs," Cubanski says, "but the public release of this information may have a shaming effect on pharmaceutical companies."

Whatever might explain, or solve, rising drug prices, it's clear they can't continue. The 12 percent average price increase per year far outpaces the current rate of economic growth in the U.S., says Gal Wettstein, a research economist at Boston Collee's Center for Retirement Research. "It's not sustainable," he adds. "We can't spend half our national income on drugs."