Updated | On January 26, during the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Oleg Deripaska, a Russian aluminum tycoon with close links to his country's government, threw a party at a luxury chalet. The champagne flowed, music pumped from the speakers, and the guests feasted on caviar. The night's star performer was Enrique Iglesias, the famous pop singer. At some point, according to photos of the event, Deripaska, 50, took to the dance floor in an open-necked shirt.

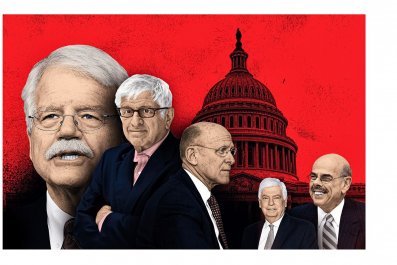

Fast-forward three months, and Deripaska probably isn't dancing. On April 6, the United States placed him on a sanctions list that included six other Kremlin-connected oligarchs, as well as numerous Russian officials and companies. The tough new sanctions prohibit American citizens from doing business with them and freeze any assets they have in the United States. Citizens of other countries who deal with the Russians on the list could also face sanctions from Washington.

American lawmakers introduced the measures in the aftermath of Russian meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election and other "malign activity," including the Kremlin's military campaigns in Syria and Ukraine. "Russian oligarchs and elites…will no longer be insulated from the consequences of their government's destabilizing activities," the U.S. Treasury Department said in a statement.

The United States has previously slapped visa bans on Russian tycoons and officials, as well as frozen their assets. But these are the first sanctions with Moscow's economic interests as the primary target. "Sanctions are no longer an instrument of altering Russian foreign policy," says Alexander Baunov, an analyst at the Carnegie Moscow Center think tank. "The new sanctions are a means of punishing Russia to the full [for its actions]."

Deripaska's inclusion on the U.S. list wasn't surprising. For years, he worked with Paul Manafort, President Donald Trump's former campaign manager, who has been charged in special counsel Robert Mueller's investigation into alleged Kremlin interference in the election. Russian opposition figures have accused Deripaska of passing on information about the Trump campaign from Manafort to Sergei Prikhodko, a Russian government official, while yachting off the coast of Norway in August 2016. Deripaska denies the allegations, and he describes the U.S. decision to sanction him as "groundless, ridiculous and absurd." (Manafort did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication. Prikhodko has denied the allegations).

There's no denying the impact, however. Deripaska's Rusal aluminum giant lost over half of its value when the markets opened for trading April 9, and his personal fortune tumbled from $5.4 billion to $3.7 billion in just 48 hours as investors worldwide distanced themselves from his businesses.

Deripaska wasn't the only Russian businessman to take a financial beating.

The country's media dubbed April 9 Black Monday after the country's 50 richest men lost more than $12 billion among them, according to Forbes. Many of them, like Vladimir Potanin, a metals tycoon who saw his net worth fall by $1.5 billion, weren't even on the list. Of those that were, Viktor Vekselberg, a billionaire investor who attended Trump's inauguration, and Suleiman Kerimov, who owns Russia's largest gold producer, Polyus, lost a combined total of almost $2 billion.

Investors also offloaded shares in Russian companies due to fears that Washington is planning further sanctions against Moscow over its backing of the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria, as well as allegations that President Vladimir Putin ordered the attempted assassination of a Russian double agent in southern England. The U.S. sanctions affected Russia's national currency too; the ruble's value dropped by almost 10 percent in just six days, its steepest decline since 1999, before recovering slightly.

Russian officials and state media had mocked previous U.S. sanctions against Moscow as weak and ineffective. This time around, no one is laughing. "The United States has taken a decisive step towards Russia's economic isolation," says Kirill Tremasov, an analyst who headed the Russian Economy Ministry's forecasting department until last year. "[This] opens a new stage in relations with Western countries. We are in a new reality."

Alexei Navalny, the opposition figurehead, welcomed the sanctions, which also targeted Kirill Shamalov, a billionaire who married one of Putin's daughters in 2013. "These people steal our money and doom our country to poverty," he wrote in an online post.

Moscow has pledged a "tough response" to the U.S. sanctions. But it's unclear what steps it can take without harming the economy. Analysts are already warning that ordinary Russians could suffer, as a weakened ruble means steep increases in prices for imported food, clothes and medicine. And based on Putin's past behavior, citizens should worry. In 2014, he responded to Western sanctions related to the Kremlin's seizure of Crimea by prohibiting the import of foodstuffs from the United States and Europe. The decision drove up domestic prices and angered members of Russia's middle class, who had to make do without Italian cheese and Spanish ham, among other delicacies. Washington's measures have already ruined Russians' summer plans by making it more expensive for them to go abroad: Travel agents have reported a 40 percent decline in the number of holiday bookings for foreign destinations.

This time, Russia's parliament is proposing a retaliatory ban on the import of an even wider range of American goods—including alcohol, medicines and tobacco—and suggested legalizing the pirating of American intellectual property, as well as a possible ban on titanium sales to Boeing. Analysts warn, however, that such moves could trigger a new round of even tougher U.S. sanctions. Other Russian officials have spoken in favor of targeting American companies that operate in Russia, such as McDonald's, Ford and Pepsi. But these multinationals employ tens of thousands of Russians and use domestically produced goods. "Russia needs to work out if the benefits of any response outweigh the costs, given the potential impact on Russian business and the Russian consumer," says Andrew Risk, a Moscow-based adviser to GPW, a British political risk consultancy.

The Kremlin also needs to keep the business elite happy, analysts say. Russia's government has pledged financial assistance for companies that employ large numbers of people, such as Deripaska's Rusal, which has 62,000 employees on its payroll. Officials are also reportedly drawing up plans to relieve pressures on sanctioned companies by creating special offshore zones inside Russia that would provide them with special tax and regulatory benefits.

But handing out tax breaks to government-linked billionaires risks exacerbating social tensions. Millions of Russians are living in poverty, and the government says there is "no money" to raise the minimum wage, which is the equivalent of $179 a month. "Instead of using money from the [national] budget for something else, it will be used to help Deripaska," said Alexei Venediktov, the head of the opposition-friendly Ekho Moskvy radio station, during an on-air discussion. "[But] the budget is your taxes."

Despite their massive financial losses, Russia's richest businessmen—at least publicly— remain loyal to Putin. "They will all demonstrate their patriotism and demand compensation…for their suffering at the hands of Russia's enemies," says Yekaterina Schulmann, a prominent political analyst. In private, however, frustration over the Kremlin's costly confrontation with the United States and its allies is likely to grow.

"People within Putin's inner circle, as well as within the slightly wider circle of the political and business elite, have seen their fortunes decimated, and they no longer have access to international capital markets," says Vladimir Ashurkov, a London-based Russian opposition figure and former top banker. "They can see that this is a result of Russia's new assertiveness abroad. They would prefer this to end."

Putin, of course, has no problem cracking down on Russia's business elite should disgruntlement turn into dissent. In 2005, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, an oil tycoon, was jailed on hotly disputed fraud charges after challenging Putin over high-level corruption. At other times, analysts say, the Russian leader has made examples of high-profile tycoons to keep the rest scared and compliant. That was reportedly the case in 2014, during an economic downturn, when Vladimir Yevtushenkov, a multibillionaire businessman, was arrested on money laundering charges that were later dropped.

Opposition figures like Ashurkov have few illusions about international sanctions helping to spur change within his country. "If Putin decides to pursue a less aggressive foreign policy but become more tyrannical inside Russia, the West will turn a blind eye, and the sanctions will be softened or even canceled," he says. "They don't care about what goes on in Russia."

This story has been updated to reflect a version of this story that appears in the May 5, 2018 edition of the magazine.