Encouraged by the controversial presidency of Donald Trump, Democrats are predicting a rout in November's midterm elections. If they are fortunate, that electoral wave could be as large as the one that swept across the country in the fall of 1974, when Dems took 49 seats in the House and five in the Senate from Republicans.

Those Democrats were liberals, and they were young, like many of the candidates hoping to win a seat in Congress later this year. "I literally looked up the word Democrat in the phone book to find the local headquarters," said Bob Edgar, who came to Congress in 1974 from Pennsylvania. Back then, idealism whisked newcomers like Edgar into the U.S. Capitol. But once there, the class of '74 discovered that politics is the art of the possible, and that what is possible is often far less than what was promised. Today's hopefuls, primed for an auspicious November, may wind up learning the same lesson.

"We were a conquering army," recalled George Miller, who was elected to the House from Northern California in 1974. But Capitol Hill proved a remarkably sturdy redoubt, despite its well-chronicled flaws.

The class of '74 was known as the Watergate Babies; the election that ushered them into office took place some three months after President Richard Nixon resigned in disgrace to avoid impeachment after the sabotage efforts against his Democratic rivals during the 1972 presidential campaign. They promised to serve as a check on Nixon's successor, Gerald Ford, but also to "restore Congress to its proper constitutional rank as a co-equal branch of government," as The New York Times wrote.

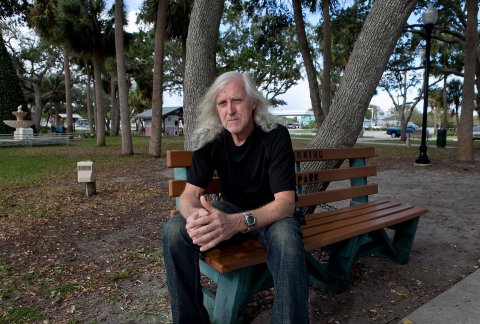

John Lawrence came to Washington with the Watergate Babies, as an aide to Representative Miller. He would remain a Miller staffer for the next three decades, before becoming chief of staff to Nancy Pelosi, the California Democrat and current minority leader. This made Lawrence "the highest-ranking staffer in the House of Representatives," as The Washington Post described him.

D.C. is a small town, and the Hill is a particularly crowded knoll where faces quickly become familiar. "I knew most of these people," Lawrence says of the men and women who came to Washington after the Democratic wave of 1974. We spoke in the Statuary Hall of the U.S. Capitol. It was a blustery winter afternoon, and Congress was trying to avoid yet another government shutdown, but he wasn't especially concerned: These marbled halls are not his workplace anymore. Lawrence, who retired in 2013, now teaches at the University of California's outpost in Washington. And he was about a month from publishing The Class of '74: Congress After Watergate and the Roots of Partisanship, his timely book on the uses and abuses of congressional power.

In 2014, Henry Waxman became the last of the class to leave the Hill. The California congressman, one of the most accomplished liberals in the House, had exhausted his political energies. "I have confidence that Congress is going to get straightened out," he told the Los Angeles Times. "They can't say no to everything." But federal lawmakers kept doing just that, even as the White House has switched from Democratic to Republican control.

For his book, Lawrence talked to Waxman and some 40 members of the class and their high-ranking aides. "Many of them really never had an opportunity to tell their story," Lawrence says. Many were also dying. And he disliked the moniker "Watergate Babies." It felt like a smear. "The pejorative characterization had always bothered me," he says.

The class of '74 came to Congress with a sense of idealism rare for anyone in Washington old enough to drive a car. But they did not ultimately usher in a glorious era of liberalism. "Sooner or later, this place gets the best of you," lamented Toby Moffett, a member of that class, to The New York Times. "You get tired. You get cynical. I think even the best of us get worn down, sidetracked, compromised to death." His weariness is remarkable only because it came after a mere three years in Congress. Jerry Ambro, a Democrat from New York, offered Lawrence a blunter assessment of his congressional classmates: "The grandiose plans never got anywhere."

The 94th Congress didn't save the Democratic Party's soul, but the idealists did enliven it. The new liberals removed three committee chairs, all of them conservative Democrats, and made chairmanships a function of caucus votes, not seniority. They gave more power to subcommittees too. In practice, this meant that younger members of Congress could bring issues of no interest to older Democrats from the South—the environmental movement, civil rights, the gender pay gap—to the fore. "Everybody got the message that you were now accountable to the caucus," Lawrence says. "This committee, or this subcommittee, was not your personal purview anymore."

In retrospect, those were significant changes. But they weren't what had been promised in the run-up to November's landslide. "Reforming the Congress was not particularly high on my list," Tom Downey, a New York Democrat who was the youngest member of the class of '74, tells me.

Downey was among those who stayed in the House, retiring in 1993 to become a lobbyist. Another member of that class, Gary Myers, a Republican, went back to Pennsylvania, to the steel mill where he'd once worked. Robert Cornell, a Democrat, returned to Wisconsin, to the Catholic Church in which he'd been raised.

Others scrambled to higher political ground. Chris Dodd of Connecticut became a U.S. senator and, in 2008, a presidential candidate. Congress rewards those who stick around. The greatest legacy of the class of '74 may not be what it accomplished but whom it minted, including Democratic leaders like Waxman and Dodd (the class was, as Lawrence acknowledges, largely composed of white men). "Wave elections provide opportunities for people to move to Congress," explains Norman Ornstein, a congressional expert at American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. "That election was a springboard."

Those who stayed experienced some success. Waxman helped pass important legislation on the environment and health care, including the Affordable Care Act, which he helped write. Dodd, meanwhile, co-sponsored the 2010 financial reform act that bears his name, and which Republicans are eager to repeal.

The class of 1974 also pioneered the art of self-promotion. Defying the norms of previous generations, they eagerly sought out the press, unwilling to play the role of silent backbenchers. Lawrence explains that many of the Democrats new to Congress had come out of the movement against the Vietnam War, as well as the civil rights and women's equality movements. These had all relied on media attention, pegged to charismatic leaders able to articulate their points, especially on television.

But the reformist spirit was largely spent playing defense. Instead of advancing new liberal policy, its members were forced to shield existing ones against an organized conservative assault. Ford was a largely ineffectual president, but so was his Democratic successor, Jimmy Carter, whose listless term Downey calls a "gigantic missed opportunity" for liberals. There weren't many opportunities after that, not during eight years of Reaganism, which—despite continuing Democratic majorities in the House—efficiently eroded the legacies of liberalism. "We were busy fighting rearguard actions to preserve elements of the New Deal and the Great Society," says Downey.

In their resistance to Ronald Reagan, Democrats employed the kind of tactics the Watergate Babies came to renounce. Jim Wright of Texas, the house speaker from 1987 until 1989, made no apologies for resorting to the very power plays the class of '74 decried. He undermined Reagan in holding his own peace talks with Nicaragua, and on the domestic front he used parliamentary tactics to such masterful effect that Dick Cheney, the future vice president, called him "a heavy-handed son of a bitch" who would "do anything he can to win at any price, including ignoring the rules."

Wright was eventually toppled by an ethics investigation, but not before proving an effective foil for Republican legislators. His foremost nemesis was a former historian from Georgia who'd come to Washington a decade before, promising Republican victories: Newt Gingrich. "If Wright ever consolidates his power," Gingrich warned in 1987, "he will be a very, very formidable man. We need to take him on early to prevent that." Seven years later, Gingrich led a Republican revolution and the GOP took control of the House, ending four decades of nearly uninterrupted Democratic control.

Gingrich ushered in a new type of politics—and the nation has never recovered. "He attacked the Congress that he wanted to lead," says Waxman, who now runs a lobbying company. "He was successful in using a very sharp edge in describing Democrats as not Americans." In 1990, a Republican organization disseminated a guide to legislators who, the publication claimed, sounded an increasingly loud refrain: "I wish I could speak like Newt." They have been speaking like him ever since, even though Gingrich—plagued by ethical troubles and dissatisfaction from fellow Republicans—has long since left the Hill to ply his rhetorical trade on Fox News.

A second Republican revolution occurred in 2010, this one powered by the Tea Party, which succeeded in undermining President Barack Obama. The Republicans who have maintained control of the House since that election (they took control of the Senate in the 2014 midterms) have routinely bickered about the most basic procedural matters. They shut down the government. They dedicated more than eight years to repealing the Affordable Care Act, but weren't able to do it. And they held exhausting hearings on the attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya, which even House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy has said were a ploy to harm the presidential prospects of Hillary Clinton.

Trump promised to bring his managerial skills to Washington, but his tweets seem to routinely scuttle legislative business, leaving House Speaker Paul Ryan and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell confused. The House Intelligence Committee's investigation into Russian electoral meddling turned into a battle of competing memoranda, one issued by Republicans, the other by Democrats. Last year's tax reform bill, its merits aside, was further evidence of how little Congress prizes cooperation—and how thoroughly it rewards partisan rancor. So it's not surprising that Congress's popularity is only 18 percent, according to Gallup; what's surprising is that it isn't lower.

Lawrence, however, remains an optimist. The nation got through Watergate. It will get through this—whatever this supremely strange moment in American politics ends up being. "The rumors of the death of democracy," he says, "are very much exaggerated."