What have humans done to deserve dogs? They greet us when we come home, comfort us when we're sad and generally act as loyal companions.

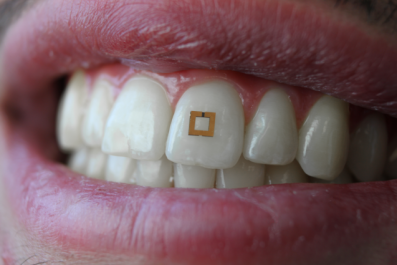

Now, researchers are investigating whether tumors in dogs may help treat tumors in humans. (Talk about loyalty.) In early April, the Jackson Laboratory, which breeds and sells research mice to universities and drug companies, began collecting samples of canine tumors. Cells from these tumors implanted into mice could help test new drugs and improve our understanding about how cancer develops and progresses. A veterinary surgical center in Connecticut that treats dogs diagnosed with cancer is providing the initial samples. But the plan is to collect many more.

The new research involves a long-used method for studying human tumors: implanting them in mice. Normally, the introduction of cancer would trigger an attack by the mouse's immune system. The mice at the Jackson Laboratory are different: Either they have no immune system or have received a stem cell transplant to make their immune systems more like those of humans. When a small piece of a person's tumor is implanted into these mice, those cells can grow in a way that is more realistic than what's possible in a petri dish. "It is the closest we have to a human tumor," says Dr. Edison Liu, CEO of Jackson, "other than a human."

Dog tumors may be the next runner-up, on account of the genetic underpinnings of the disease. Although cancer results from many factors, genes play an integral role, and sometimes an inherited mutation can increase a person's risk. Other times, a healthy gene may change, leading to the abnormal cell growth—the defining feature of cancer.

The genetic makeup of a tumor can also determine which drugs work against it. Having a broad and diverse array of genetic profiles increases the chances of finding the right way to attack each disease. This thinking is particularly relevant for rare cancers and rare mutations. Drawing from a larger pool means more genetic mutations to research.

And using tumors from dogs is a nearly ideal way to widen that pool. They're exposed to many of the same environmental factors that might trigger cancer in their owners, notes Dr. Christopher Fulkerson, a veterinary medical oncologist at Purdue University. Some bone, brain and bladder cancers are far more common in dogs than they are in people, making samples easier to find.

In many cases, the cells in a dog's cancer look and act the same as they would in a human. They can even carry the same underlying genetic mutations. For example, in both human and dogs with chronic myelogenous leukemia, two genes called BCR and ABL are fused in a very familiar way.

Read more: Why cats' tumors aren't so useful for human cancer research

Despite the pieces of real tumors growing inside them, these mouse models of human tumors aren't perfect. In a 2017 Nature Genetics paper, one group of researchers cautioned that the genes of human tumor samples might change once they're in mice, potentially making the results of some experiments less relevant. The same could happen with implanted dog tumors.

Not all canine cancers will be particularly helpful for human-focused research. For some types, the similarities between human and dog diseases will be significant. But when they aren't, cautions Dr. Jaime Modiano, a comparative oncology specialist at the University of Minnesota, the differences could have serious implications for drug development.

But even when the research doesn't advance knowledge of human malignancies, it could still help improve the treatment of dogs diagnosed with cancer. That's the least we can do for our faithful friends.