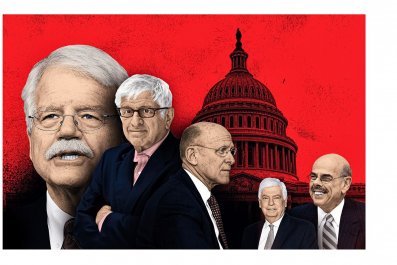

Three decades ago, Konstanty Gebert broke the law. Constantly. He took part in anti-government protests. He wrote for underground newspapers. And he helped organize a secret university that taught subjects forbidden by the state.

But since the fall of Poland's Communist government in 1989, Gebert says, he's tried to respect the rule of law that Poles fought so hard for. That is, until earlier this year, when Poland's ruling far-right Law and Justice Party (PiS) made it illegal to blame the country for Nazi atrocities during World War II. Gebert felt he had to speak out. So in March, days after the law went into effect, the 64-year-old Jewish journalist made such a claim in an article for his Warsaw-based newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza. "Many members of the Polish nation," he wrote, "bear co-responsibility for some Nazi crimes committed by the Third Reich."

For now, Gebert remains a free man, but as a result of his article, he faces a three-year prison term or a sizable fine. "I'm still waiting," he tells Newsweek. "The prosecutor's office has published a press release saying that there have been 44 complaints based on the new law and they are examining them. I hope I am on the list."

Warsaw has argued that the law protects the country's history by outlawing claims that Poles were involved in Nazi death camps such as Auschwitz, which is near the town of Oswiecim. Between 1939 and 1945, Poland suffered a brutal occupation by the Nazis, who killed up to 3 million Polish Jews and 2.5 million ethnic Poles. Yet every year, Polish Deputy Foreign Minister Bartosz Cichocki says, the country's embassies overseas record more than 1,500 instances in which people blame Poland, not Germany, for Nazi atrocities. This includes everything from references to "Polish" death camps, to allegations that Warsaw collaborated with Adolf Hitler during World War II. "We [have] witnessed a wave of articles, opinions and commentaries which prove that many [people] have no basic knowledge about the history of Poland," he says. "The situation we have somehow [is] that when people think of the Holocaust…there are only Jewish victims and Polish perpetrators."

But critics of the bill say it's a broad, vaguely worded assault on free speech, designed by the PiS to muzzle critics and stifle historical debate. "It is a general bludgeon blow that is supposed to be hanging over the heads of people who want to discuss the Shoah," says Gebert (using the Hebrew word for the Holocaust), "to make sure that the government can hit them any time that it considers it politically expedient."

Many Poles resisted the Third Reich, and Israel's Yad Vashem Holocaust Center recognized more than 6,000 of them as "members of the righteous" for sheltering or helping Jews to escape the Nazis. For Poles, the country's anti-fascist resistance during World War II is a source of pride and national identity. "Poland never created a government that collaborated with the Third Reich and never formed an SS division," Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki argued in Foreign Policy magazine in March. "My close family rescued Jews. [In] the darkest hour Polish-Jewish bonds proved to be stronger than the unimaginable brutality of the Nazi German occupation."

But over the course of almost three decades—especially since the government released archives after the fall of Communism in 1989—new scholarship has highlighted a darker issue: collaboration. In 2001, Jan Gross, an American-Polish historian, sparked a nationwide debate when he published Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland, which examined the 1941 murder of 340 Polish Jews who were locked in a burning barn by local villagers. In 2006, Gross published a second book, Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland After Auschwitz, which documented violence against Jews in the years following liberation from the Nazis.

The allegations went further. In 2013, another Polish historian, Jan Grabowski, published Hunt for the Jews: Betrayal and Murder in German-Occupied Poland. His book meticulously analyzed records in a single rural district of Nazi-occupied Poland, Dabrowa Tarnowska, and showed that the vast majority of Jews who hid from the Nazis were betrayed—and in some cases murdered—by their Polish neighbors.

Both historians say this violence did not end in 1945. A year later, in the village of Kielce, Polish police, soldiers and civilians killed over 40 Jews who had survived the Nazis. "This eruption of anti-Jewish violence [was] not an isolated outburst of hate," Grabowski writes, "but rather a declining continuation of a wartime practice, familiar to people across the occupied land."

For historians like Grabowski, coming to terms with Polish collaboration in crimes during the Nazi era is important not only for Poland but for the world. "I believe that the actions of human beings are somehow universal," says Grabowski of his research into Dabrowa Tarnowska. "Your neighbor asks for your help. If you help him, you could be killed, but if you don't, he could be killed. All these horrible choices you have to face…they need to be discussed."

Many Poles, however, don't seem to agree. A 2017 survey by the Warsaw-based Polish Center for Research on Prejudice showed that more than 55 percent of Poles were "annoyed" by talk of Polish participation in crimes against Jews. "In Poland, not only the occupation and war [but the] wartime attitude to Jews has never been thought through," says Grabowski. "It has been plastered over and made to go away."

For Poland's nationalist far right, claims that the country took part in the Holocaust have fueled the argument that the country is under attack from both European and foreign forces. Like Prime Minister Viktor Orbán in Hungary, PiS founder Jaroslaw Kaczynski has battled with the European Union over demands that member states accept a quota of migrants. And just as Orbán used the history of Hungary's unfair treatment after World War I to bolster his nationalist credentials, so too has Kaczynski invoked the demons of World War II. In 2016, Poland angered its allies in Kiev by passing a resolution that accused Ukrainian collaborators of murdering 100,000 Polish civilians during World War II. That same year, Warsaw threatened to strip Gross, a professor at Princeton University, of the Order of Merit, Poland's highest honor, for writing an article in the German newspaper Die Welt saying that Poland "kill[ed] more Jews than Germans during the war." And in 2017, soon after the PiS assumed power, the government demanded that Germany pay more than $850 billion in compensation for war crimes and the destruction of Polish cities.

The official target of the Holocaust law is the use of the term "Polish death camps" to describe Auschwitz and other Nazi facilities. But critics see the argument as a straw man. Not only was the phrase almost unheard-of before 2015, but even revisionist historians do not argue that Poles set up the death camps. "If you think that [the issue of Polish death camps] is the object of the law, then you are deluding yourself," Grabowski says. "It is a question of who slanders the Polish nation.… This law is a noxious and toxic one."

Toxic or not, the bill plays well with Kaczynski's base. In April, the far-right National Movement called for Israeli President Reuven Rivlin to be investigated after he told Polish President Andrzej Duda that Polish collaboration with the Nazis "could not be ignored." With local elections at the end of 2018 and national elections the following year, the timing is not a coincidence, according to critics of the Holocaust law. "If the government retreats, it stands to lose the fascist vote—that is some 10 percent of the electorate," says Gebert. "Kaczynski needs to hug his fascists very close to his chest."

But if giving fascists some love was Kaczynski's intention, Warsaw has paid a heavy price for it internationally. Even party hard-liners have been shocked by the furor that greeted the passage of the law in January and has dogged it since. Washington has accused Poland of a brazen attack on free speech, while Israel has said the legislation is akin to Holocaust denial. Already in an ugly spat with the European Union over its reforms to the judiciary, Poland found itself with a rapidly diminishing pool of allies.

Prime Minister Morawiecki made a bad situation worse on February 17 when he told a panel discussion at the Munich Security Conference that Jews—as well as Poles and Russians—were "perpetrators" during the Holocaust.

His comments followed a question by Israeli journalist Ronen Bergman, whose family is Polish and whose mother and father survived the Holocaust. In an emotional statement, Bergman explained how his mother's family was betrayed by their neighbors during the Nazi occupation of Poland. For Bergman, Morawiecki's response demonstrated that the debate over the law is as much about the present as it is the past. "I am so full of emotion, I am almost in tears," he says, referring to the widely shared video of the exchange. "I thought [Morawiecki] would say something like I am sorry for your loss. Instead, he looked at me as if I was some kind of a nuisance. It became clear to me…that we are not just discussing history."

If the Polish prime minister's comments to Bergman were dismissive, then the backlash from nationalists was stinging. Rumors spread online that Bergman's family had handed over Jews to the Nazis. Far-right trolls trawled through and criticized his work on extremist websites. In northern Israel, in an attempt at intimidation, somebody tracked down and photographed his mother's grave. "Horrific, horrific things," Bergman said of the messages he received online. "It was an organized campaign. This was not a spontaneous outburst of nationalistic feeling. This was my first confrontation with something [like this], and it left a stain."

It would be easy to dismiss those who targeted Bergman in the wake of his comments in Munich as a fringe minority of trolls, hiding behind online anonymity. But statistics collated by the Polish Center for Research on Prejudice suggest that anti-Semitism is not only widespread in Poland but growing. A survey carried out by the organization in 2017 found that between 2008 and 2013, the number of Poles who believed that Jews perform ritual murder rose from 12 to 24 percent. Meanwhile, 85 percent of respondents said they had never met anyone Jewish in Poland.

That's an unsurprising statistic, given that two-thirds of the 300,000 Polish Jews who survived the Holocaust emigrated to Israel after the war. Another 20,000 left Poland in 1968, when the Communist government launched an "anti-Zionist" campaign targeting its critics within the Polish intelligentsia. According to the country's last census, in 2012, just 8,000 people defined themselves as Jewish.

Poland's government, which has strived for closer relations with Israel, denies that anti-Semitism is on the rise. Cichocki, the Polish deputy foreign minister, claims it's unfair to accuse the country of anti-Jewish hatred when neo-Nazis are marching in the streets of U.S. cities and Jews are being attacked and murdered in Europe. "Poland is a safe haven for Jews," he says.

Cichocki also argues that the bill is equivalent to legislation that criminalizes Holocaust denial in 16 European nations, as well as Israel. And, he points out, Warsaw's government has funded research, exhibitions and museums that document the more controversial aspects of World War II. These include the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, which opened in 2013 on the site of the former Warsaw ghetto. "We are not afraid of the darkest pages of our history," he says. "This law is not penalizing people who say that…Poles or groups of Poles participated in German atrocities. Nobody is limiting freedom of speech in Poland."

In the face of U.S. and Israeli condemnation, Poland's Ministry of Justice has yet to prosecute anyone for violating the Holocaust law. In March, Duda referred the bill to Poland's constitutional court, which has yet to issue a ruling. Critics see the move as an attempt to distance the government from what is an increasingly toxic political issue.

Indeed, some say Kaczynski may be hoping that the court—which is packed with party loyalists—will recommend changes to the law, making it more palatable to Israel and the U.S., without angering his nationalist base. The PiS is seeking a two-thirds majority in parliament in 2019, meaning he cannot afford to be seen as weak by the far right.

It's a delicate balancing act, analysts say, and even if Kaczynski ultimately decides it is worth Poland becoming an international pariah in return for a major win next year, Gebert is optimistic. There has been considerable opposition to the bill at home and abroad, including open letters, protests and statements from religious and political groups.

During the March 1968 anti-Zionist campaign, he recalls, Poland's Jews had no allies. It marked a formative moment for him, and not only because he received his first beating by riot police. It was when his generation realized that the Communist system could not reform, that it needed to be overthrown. And they would have to do it alone.

Fifty years later, that's changed. "The fundamental difference is that this time…we are not alone," he says. "There is an internal debate within Polish civil society about the kind of country we want to have. The opposition stands with us. There have been public condemnation of this law, solidarity with the Jews, demonstrations."

Perhaps that is why Gebert feels not just confident but comfortable with breaking the law. "It was not an easy decision," he says, "but I am breaking it to find out what it says."