As Nigel Farage embarks on his second pint of bitter, I read him a paragraph from Hunter Thompson's Rolling Stone obituary of Richard Nixon. "Some of my best friends," Thompson wrote, "have hated Nixon all their lives. My mother hates Nixon. My son hates Nixon. I hate Nixon, and this hatred has brought us together. Nixon laughed when I told him this. 'Don't worry,' he said. 'I too am a family man, and we feel the same way about you.'"

This kind of collective detestation, I tell Farage, closely reflects the attitudes expressed by my friends when I mentioned I was coming to meet the United Kingdom Independence party (Ukip) leader.

If history suggests that the ability to inspire hatred can be a perverse indicator of greatness in a politician, then who knows what heights Nigel Farage might scale? How many of us could really be driven to fury by such figures as Ed Miliband, David Cameron, or poor bewildered Nick Clegg? These are men who, I suggest to Farage, might have collaborated to develop a homogenised image you could brand as SBW: Smart Boy Wanted.

"They are appalling people, truly appalling," Farage says, of his fellow party leaders. "Every one of them is as dull as bloody ditchwater. These men are thoroughly hopeless."

"By what definition?"

"I judge everybody on the Farage Test. Number one, would I employ them? Number two, would I go for a drink with them?"

I am one of many to have satisfied that second requirement. We have adjourned to the Alexandra Hotel in Chatham, Kent, where Farage is unwinding after an afternoon of canvassing on behalf of the most recent defector from the Conservatives, Mark Reckless. According to a Survation poll published last Sunday, Reckless holds a nine point lead in this Rochester constituency.

The day didn't begin quite so well. Ukip activists can be somewhat wary of journalists. When I first arrived I approached one group and asked where I might find Farage, at which point one or two gave me the kind of look you see on the faces of locals at the village inn in a Dracula film, when a foreigner calls in and asks for directions to the castle.

But the Ukip leader's habitual ebullience appears to have been shifted into overdrive by the welcome he has received in the Medway towns. Walking at his side as he toured the streets, I'd expected him to be greeted, at least occasionally, with a salvo of abuse. Instead he was received – everywhere – with an enthusiasm verging on euphoria. Here in the pub, our conversation is interrupted every few minutes by admirers.

A name like Nigel Farage, were it to appear in a historical novel, might indicate a tendency to foppish indolence and swagger. But you don't need to talk to the politician for long to realise that the perception of him as a clown is seriously mistaken. Historically, the popular press has focussed on his history of vehicular misfortune, both terrestrial (he was almost killed as a young man when he staggered in front of a car, while drunk in Orpington) and airborne: in May 2010, while attempting a "fly-past" in a light aircraft, his Ukip banner became entangled in the tail-fin. The plane fell to earth from 11 metres, breaking his sternum. Nautical catastrophe has so far eluded him, but Farage is still only 50 and a keen sea angler.

It's undeniable that, in his battle to embody such qualities as fidelity and temperance, he has suffered the occasional reverse. Eight years ago, Farage established an improbable entente with a 25-year-old Latvian at a pub in Biggin Hill, Kent. She told the News of the World (falsely, insists the Ukip leader) that they made love seven times and that she performed "sex acts with ice cubes" which left the MEP "snoring like a horse".

Such stories, like his fondness for Rothmans and tireless conviviality on licensed premises, don't seem to have damaged his relationship with the electorate. A woman approaches Farage, who is wearing his trademark blazer and tie. Heavily tattooed and in her late twenties, she doesn't look like a natural Ukip supporter. She shakes his hand.

"How do you feel," he asks, "about the other parties?"

"Wankers," she replies.

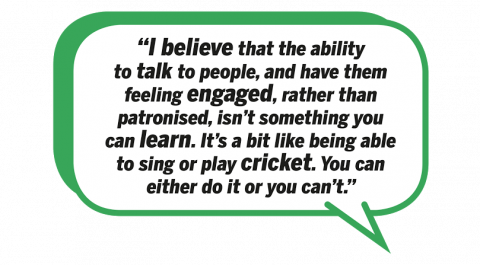

Nigel Farage has a rare ability to communicate, both in formal debate, on television and in person. This extraordinary capacity to connect represents, I suggest, a kind of genius, and renders him, from his enemies' perspective, a very dangerous animal indeed.

"I do believe," Farage tells me, responding to that last phrase, "that other politicians perceive me in that way. Oddly enough David Blunkett said the very same thing to me, not long ago."

"How do you manage it?"

"I believe that the ability to talk to people, and have them feeling engaged, rather than patronised, isn't something you can learn. It's a bit like being able to sing or play cricket. You can either do it," he explains, "or you can't."

We have met once before, almost three years ago. On that occasion, Farage, never one to leave the views of an interviewer unchallenged, swiftly established that we differ on every significant issue, with the exception of his fierce objection to the lack of democracy at the heart of the European Union. That organisation was recently described by the maverick economist Max Keiser as, "somewhere that poses as an elite club, but actually is a leper colony whose members spend their time looking to see who has got the most fingers left."

For all that, I find Farage impossible to dislike, mainly because, in marked contrast with other party leaders, there is, if I can employ a Northernism, no "side" to him. As the filmmaker Mark Durkin concluded, in his outstanding recent TV documentary Nigel Farage: Who Are You?, the more you speak to the Ukip leader, the more you realise the futility of searching for the hidden man: there just isn't one. He is what he is.

When we last collided, in early 2012, the notion that Farage might play a pivotal role in the 2015 election seemed fanciful in the extreme. I remember saying, back then, that listening to him express hopes about achieving real political power felt like travelling up the motorway with a seven-year-old tugging at your sleeve, pestering you to let them drive. What if you agreed? Where would you wind up? In a cell at Strangeways prison? Safely parked near a pub in Carlisle? Or crawling from the wreckage, having crossed some stranger's lawn and crashed through the doors of their . . . . "How was it," I ask the Ukip leader, "that you told me you pronounce the place where you keep your car?" "Gárage," he replies. "Like Fárage."

"Things have moved on a bit, haven't they?"

"Since you and I last met," he replies, "the whole of Ukip has changed. We established ourselves by saying clearly what we were against. Back then at a Ukip meeting, you could touch the G spot of an audience just by saying how appalling some Brussels commissioner was. What people are interested in now is: what are we going to do? With our seats on councils, and our members of parliament."

What my friends are asking, I tell him, is how we're going to keep him out.

"Why?"

"They hate you."

"Oh. Do they know why?"

I explain that they attribute to Farage a degree of racism that, in the time I've spent with him, has never been expressed either in thought or action.

"I refute and resent that."

"So you've been misrepresented?"

"We started the European election campaign," Farage replies, "with a tiddling percentage of people thinking Ukip was a racist party. We finished with nearly a third of the country believing we were racist. That hatred was whipped up by elements of the print media. Our people were getting their teeth punched out. Foul things happened. And" he adds, "it wasn't fair."

"How did that affect you personally?"

"It got to me, to be frank with you. It left me with a slight grudge against the print media. It upset me. Ukip believe that immigration can be an extremely positive thing. But it has to be controlled."

At this point we're interrupted by Sylvia, a woman of middle Eastern appearance.

"I love you," she tells Farage. "I don't speak very good English. I am Armenian. I am in the UK since 2007. In few years English people will be out. Who will take over? Muslims. Muslims," she adds, "are like . . . " As she ponders the analogy, I can feel Farage adopting brace position. "Scorpions," she says.

"Well," he replies, "Your homeland is a very troubled part of the world."

"Keep going," Sylvia says.

Farage grew up in Orpington, the son of a City trader. He left Dulwich College after completing his A levels, and worked as a broker before taking charge of Ukip in 2006. Clare Hayes, a nurse who attended him after he was knocked down, became his first wife. He has four children: two sons with Clare, both now grown-up, and two daughters with his current wife, Kirsten Mehr, a German national he married in 1999.

Months after recovering from his traffic accident, Farage was diagnosed with cancer in his left testicle. In 2004, I remind him, a woman reporter wrote a profile that began: "I am quite relieved that Nigel Farage has only one testicle."

"That," he says, "was offensive beyond belief. Can you imagine a male journalist ridiculing a woman who has had a breast removed?"

His impressive record as a performer on broadcast media suffered something of a setback earlier this year when James O'Brien of LBC radio pointed up the contradiction between Farage's having married a German, and a statement he had made to the effect that he became uncomfortable when he heard rail passengers speaking in foreign languages.

It's the kind of sentiment, I tell him, that I last heard expressed by my grandparents' generation, and they were raised by Victorians.

"What I said was that I got on a train at Charing Cross. It was a stopping service, to Kent, and it wasn't till we'd passed Grove Park [Lewisham, South London] that I heard English spoken. I was reflecting an unease felt in many parts of the country."

It's easy to forget that, historically, opposition to the EU, on the grounds of its lack of thrift, democracy and the unending Kafkaesque struggle to sign off on its own accounts, has been articulated by politicians from all parties, most powerfully by the late Tony Benn.

Benn, Farage agrees, was "consistently very good on Europe."

"And that's what makes it such a shame that you come out with things like your Charing Cross remark. What you need," I tell Farage, "is to draw from a broader base. Take your blazer. Every time I see you I'm looking behind you for your caddy."

"I like golf," says Farage. "And if I got too guarded I would stop being myself."

The handful of activists I met in Rochester were a mixed bunch. One canvasser launched into a heart-felt speech in defence of benefit claimants unfairly stigmatised by recent legislation. He was a member of Militant in Liverpool, in the early 1980s. His kind of background is atypical, but not unique.

"Do you concede that there are Ukip members that you should have expelled far earlier than you did? Mr Bongo Bongo Land, for instance." (Godfrey Bloom, who used this offensive phrase, among others, belatedly excluded a year ago).

"Over the past two years," Farage replies, "I have been ruthless in that respect. I really have."

"How many have you kicked out?"

"Loads." A pause. "Well . . . not loads."

"Hundreds?"

"Dozens. I have rooted out a lot of, er . . . "

"A lot of what?"

"Religious people that try to take over, racists, and the genuinely nutty."

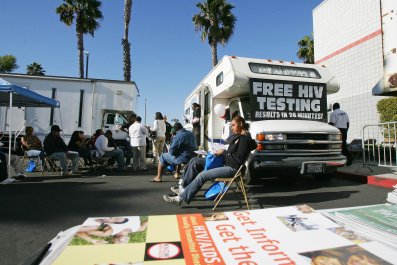

"What worries many people," I tell him, "is that the current government, unable to curtail EU immigration, seem to be victimising would-be migrants from elsewhere. I think most people who know Harare, say, would feel that any Zimbabwean seeking to come to Britain should be given every encouragement. But Zimbabweans come, to put it bluntly, with the wrong skills, in the wrong colour skin and possibly, given the HIV rates there, in the wrong state of health."

"They are discriminated against because we have an open door into Europe. Today," he adds, "if you're an Indian engineer, say, your chances of admission are limited. Ukip want to control the quantity and quality of people who come."

"Quality? How do you define quality people?"

"It's simple. That Latvian convicted murderer shouldn't have been allowed here."

"So quality means people without a homicide conviction?"

"Yes. And people who do not have HIV, to be frank. That's a good start. And people with a skill."

"What are those words inscribed under the Statue of Liberty? 'Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses . . . ' What you're saying is: 'Bring me your electricians, your merchant bankers and your guys without HIV'."

"There are 190 countries in the world," Farage claims, "that operate like that."

"Does that make it right?"

"That," he says, "is what Britain should do. I have never said that we should not take refugees. We have a proud record of accepting refugees, and that must be continued."

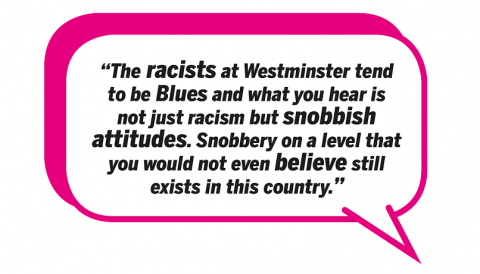

"Ever run into any racists at Westminster?"

"Christ, yes."

"And what party did they belong to?"

"They tend to be Blues. And what you hear is not just racism but snobbish attitudes. Snobbery on a level that you would not even believe still exists in this country."

The question for Ukip, and Farage in particular is, if not now, when? And how far does his ambition extend?

"Do you want to be prime minister?"

"I think that is extremely unlikely. If you asked me whether, by 2020, a completely new political party could have a majority in the House of Commons, I'd say that is very possible. But there are two types of people in politics: those who want to be something, and those who want to do something. And I want to do something. I want to build a more positive and a happier society."

"An aim more easily accomplished if you are a cabinet minister?"

"Yes. Of course. What I will say is this: if things go well next spring, I would like to be Minister for Europe."

"Pardon?"

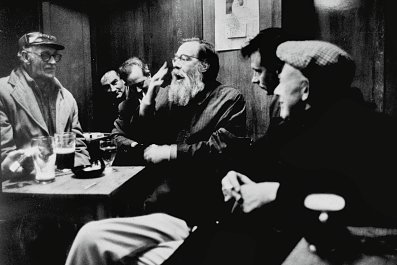

"I mean that quite seriously. I would like to be the person who goes to Brussels and says, 'We want to trade with you. We want reciprocal relationships. But this European Treaty doesn't work for us, and so we are breaking it. I would like to be remembered," he continues, "as the man who reclaimed our independence and our democracy. We used to fight for democracy. Democracy used to matter. We now treat it with contempt. We have turned our backs on values that we built up over hundreds of years, for the benefit of politicians in Europe. To me, that is heartbreaking." The traditional notion of Ukip as a bunch of demented old duffers who resemble the fishing party from the film One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, and who totter out every few years in a confused state, en route to what they believe to be the polling station, is long gone.

The likelihood is that, after the general election in May, the political landscape of the United Kingdom will have altered for ever. And, once it has, who knows what dormant beasts will find their feet, step forward, and prosper?