Few government policies today are as controversial as Obamacare, but love it or hate it, the overall impact may not be as big as you think.

Take a main goal of Obamacare: to decrease the number of uninsured Americans—or as the Obama administration puts it, to provide affordable insurance to all Americans. According to early estimates, 8 million Americans have signed up on the exchanges. That sounds like a lot, but it's unclear just how many of them were previously uninsured. Rand Corp., a nonprofit global policy think tank, estimates that up to three-fourths of the exchange customers, as many as 6 million, previously had insurance. Yet it is thought that millions more Americans have health insurance now, thanks to the expansion of Medicaid and coverage of more 20-somethings through their parents' plans. RAND calculates that 9 million formerly uninsured Americans now have health insurance because of Obamacare.

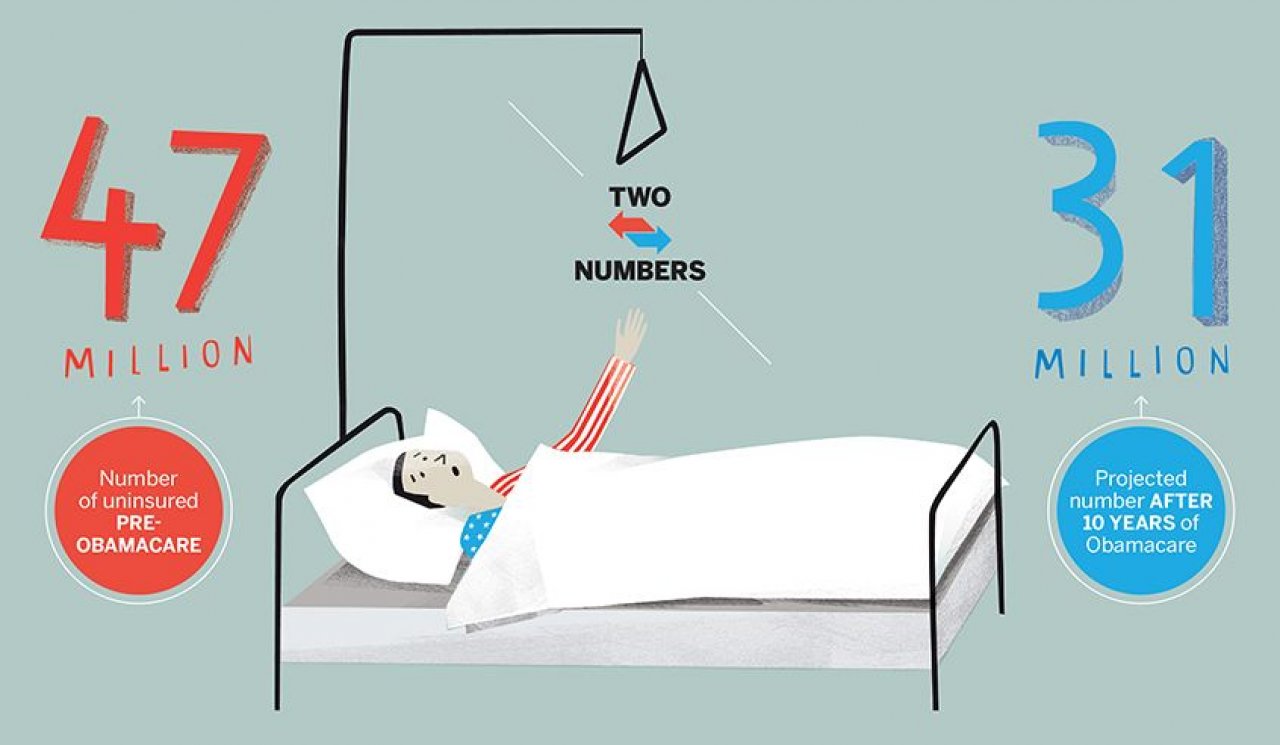

Nine million more Americans with coverage is a real accomplishment. But that reduces the problem by only 20 percent. What's more, things won't be much better over time. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that after 10 years of Obamacare, 31 million people in the U.S. will still lack health insurance.

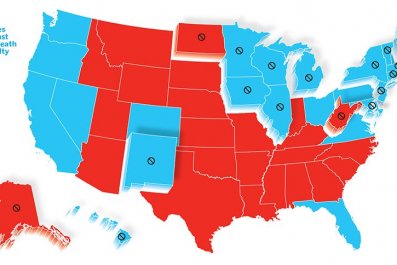

Out of those 31 million uninsured, the CBO posits that one-third may be in the country illegally. The rest might be ineligible for Medicaid because they live in a state that has chosen not to expand coverage or choose not to enroll in Medicaid. Some of the rest simply decide for whatever reason not to obtain health insurance.

But if around 10 percent of the population remains uninsured despite Obamacare, that means the U.S. still faces a substantial coverage gap. The Obama administration can take credit for progress toward the president's goals, but every other wealthy nation in the world solved this problem a long time ago. Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand and all of Europe provide health insurance to all. Yet for now, the United States seems content to shrink the problem rather than solve it.