The wordsorganic farm typically conjure visions of abundant facial hair, leather jewelry and bug-infested vegetables. But Urban Organics blows that image right out of its tilapia-filled water. The indoor aquaponics farm in a former brewery not too far from where the Mississippi cuts through downtown St. Paul, Minnesota, is almost laboratory-clean, and Dave Haider, who acts as head farmer, looks like Richie Cunningham from the 1970s sitcom Happy Days.

It's a huge, airy space, completely climate-controlled, filled with racks of vegetables that reach up to the ceiling. There's no dirt—plant roots are suspended in water that flows through the racks like a gentle river. On the far wall past the vegetables, large, circular, windowed tanks of fish reside on raised platforms four feet off the ground. The platforms look like big decks, and pipes connect the fish tanks to the racks of plants. Bugs? Not a one—but if workers do find one with their Integrated Pest Management system, it's dealt with sans pesticide, in compliance with organic guidelines from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Haider and co-founders Fred Haberman, Chris Ames and Kristen Koontz Haider ask visitors to clean their feet at the door so as not to track in anything unsavory.

Aquaponics combines plant cultivation and fish farming: Fruits and vegetables are grown in water reservoirs that also house fish. The fish waste fertilizes the plants, and they, in turn, clean and filter the water. This symbiosis is an ideal example of the type of closed-loop, waste-free sustainability championed by green advocates: There are virtually no unusable byproducts, and there's little you need to add to the system to keep it going.

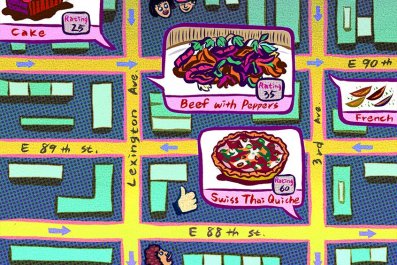

Humans have known for centuries that this works. Ancient civilizations (in Central America and Southeast Asia, for example) did a rudimentary version of it, planting crops on floating river islands and utilizing the waste of wild, local fish to fertilize them. The system is still used today in various iterations: by home hobbyists; some restaurants, such as Moyo in South Africa; and even by other urban farms, like London's Grow Up, Green Acre Aquaponics in Florida and FarmedHere in Chicago.

But it has never been done quite like this. To succeed as a large-scale commercial venture, the Urban Organics team had to solve what had been an intractable problem: filtration. If waste collects in the fish tanks, disease blooms and fish die. If the water doesn't have the right chemical balance, veggies won't flourish. Aquaponics enthusiasts have developed filtration methods that work at the hobby level but don't necessarily work when enlarged to a commercial-sized project. Haider, who worked as a landscaper for nine years, was charged with tinkering with that puzzle. Luckily, midway through the experiment, Pentair came calling.

Pentair Inc., a massive global company, does a lot of things, but one of its main subsidiaries is Pentair Aquatic Ecosystems. Pentair is headquartered in St. Paul's twin city, Minneapolis, and it heard about what Urban Organics was doing and worked with Haider to create a bespoke filtration system. Pentair CEO Randall Hogan says the company is discussing ways to apply this new technology to commercial aquaponics that can be both profitable and sustainable in other parts of the U.S., as well as the Middle East, Latin America, Asia and Scandinavia.

At Urban Organics, tilapia swim in five round, 3,500-gallon tanks, which are built up off the floor in order to "gravity feed" their waste into the high-tech, two-tiered filtration system. If the fish tanks were on the ground (at the same level as the filtration tanks), the water would have to be pumped out. But because they're off the ground, wastewater can simply be drained out of the bottom. According to Pentair's vice president of technology, Phil Rolchigo, gravity feeding reduces the number of pumps needed, thus reducing the energy used.

The first step of the filtration system pulls out solid waste, and the next converts ammonia in the water into nitrites via friendly bacteria and tiny plastic paddlewheels. With only two atoms of oxygen, nitrites are not yet ready for prime time, as far as plant food goes. They need to be nudged into nitrates (via a different friendly bacteria), which have three atoms of oxygen and make great fertilizer. Once that's done, a pump brings the water to the veggies, which are not in soil but instead sit in blue rafts with their roots dangling below, soaking up that nutrient-rich cocktail. The water then flows through further filtration, which catches any leaves and other flotsam, and is finally returned to the tanks by the other two pumps. The pumps automatically speed up or slow down as needed, ensuring they work no harder than necessary—further reducing energy output and cost.

It is a closed-loop system that needs only 2 percent of the water used in traditional agriculture. There are virtually no wasted resources.

There are other advantages, too. The plants receive 16 hours of light a day from large fluorescent fixtures 12 months of the year, making it possible to produce locally grown organic vegetables in the dead of winter (and in Minnesota, that's from October to May). And they grow so fast that production offsets the energy costs of the building—which are only 40 percent of the energy used in the same square footage of Class A (premium office space that commands high rent) to begin with.

It's 35 days from seed to first harvest, about half the time of a plant grown outdoors, and the edible parts of each plant are harvested twice a week and sold through a local chain of grocery stores. The fish take up to a year to reach maturity, and they are sold to the same local markets. Keeping things local is an important, carbon footprint–reducing element of the process.

The Urban Organics team calls it "reimagining farming," and feels its experiment, if successful, could ease the world's energy, food and water crises. The system is fully sustainable and tightly controlled and isn't reliant on soil quality or the weather. As a result, they always know exactly when they'll have products for their customers.

"Food deserts are business deserts; they're job deserts," Haberman says. "What we're trying to do here is prove the economic viability of aquaponics in an area that needs urban renewal. When that happens, jobs are created directly and indirectly, and the culture of food in a particular community begins to change for the better." A food desert, according to the USDA, is an urban neighborhood or rural town "without access to fresh, healthy and affordable food. Instead of supermarkets and grocery stores, these communities may have no food access or are served only by fast food restaurants and convenience stores that offer few healthy, affordable food options." Most everyone agrees that when the local gas station is the only place to buy food, something needs to change.

The old Hamm's brewery that houses Urban Organics used to employ much of east St. Paul, including Haider's great-grandfather. It closed in 1997, and the surrounding neighborhood turned to blight in the years it sat empty. One of the brewery's buildings was perfect for what Urban Organics needed: thick walls and floors that hold both heat and cold well, and plenty of space. It also didn't hurt that the city of St. Paul ponied up $150,000 toward the purchase as part of an urban renewal initiative. St. Paul's probably pretty happy with its investment: Since the farm set up shop, three restaurants have opened in the neighborhood.

Haberman would love to see thousands of farms like Urban Organics around the globe, particularly in hunger hot spots. And experts can see the potential. "It's intriguing for urban applications, in places with sufficient capital, technology and consumer demand," says Paul Guenette, executive vice president for communications and outreach for ACDI/VOCA, an international agriculture nongovernmental organization. However, the experiment might not work everywhere; industrial-strength aquaponics is unlikely to succeed in the most severely impoverished parts of the world, says Guenette, due to weak infrastructure.

In the meantime, Urban Organics is growing its operation. It has fully utilized only the first floor of the six-story building, but the second floor is being built out, and now the small fry are raised there until they are big enough to go into the first-floor tanks. Once all six floors are operational, Urban Organics could be growing more than 700,000 pounds of produce and 150,000 pounds of fish per year, which would make it one of the largest indoor aquaponics farms in the world. Right now the farm raises tilapia, two kinds of kale, Swiss chard, cilantro and parsley, but Haider often experiments with different plants and fish. Someday soon, Minnesota groceries might be stocked, year-round, with a huge variety of Urban Organics produce and seafood—all locally grown, sustainably farmed and affordable.