In late August of last year, as bureaucrats in Colorado and Washington state were busy setting up legal marijuana markets, the U.S. Justice Department issued a memorandum to federal prosecutors across the country. The document, whose subject line—"Guidance Regarding Marijuana Enforcement"—was a study in understatement, announced a major change in federal drug policy. The feds would allow Colorado and Washington to go forward with full legalization—the result of statewide referendums in 2012—even though marijuana remained illegal under federal law.

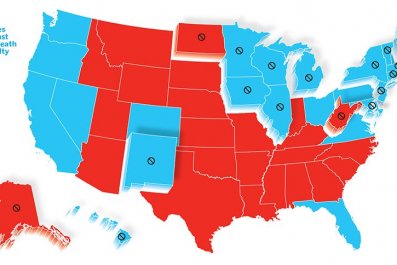

The so-called Cole Memorandum—named for the deputy attorney general who issued it—contained one glaring omission, however. It spoke only to "states and local governments" and failed to mention the oldest self-governing political bodies in the United States—Indian tribes. Tribal governments decide what the law is on the 326 Indian reservations that border more than 25 U.S. states, from New York to California.

In August 2013, tribal legalization may have seemed like just an interesting hypothetical. But by the start of this year, it had become a real possibility that the next government to legalize marijuana in the United States might be tribal. In January, the economic development committee of the Oglala Lakota Tribal Council approved a proposal to put to a popular vote whether to legalize marijuana on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, in southwestern South Dakota. The proposal has yet to be approved by the full tribal council. But should it succeed, it may open a new and complicated chapter in the national marijuana debate and have significance well beyond the 30,000 or so Oglala Lakota living on Pine Ridge.

For one, it could set off a cascade of similar efforts. "I know other tribes are watching us to see how this turns out," said Garfield Steele, an Oglala Lakota tribal councilman who supports legalization.

In fact, at least two dozen other tribes are "at different points with respect to internal decision-making processes about whether to pursue a change in tribal marijuana laws," according to Troy Eid, who chaired the Indian Law and Order Commission, an advisory board created by Congress to address criminal justice in Indian country. "And the first time a tribe purports to do this, there will be even more interest from other tribes."

That raises the prospect of a coast-to-coast patchwork of not only 50 states but 326 reservations with divergent marijuana laws—a prospect that could push Congress to clarify the murky legal status of marijuana in the U.S. sooner rather than later.

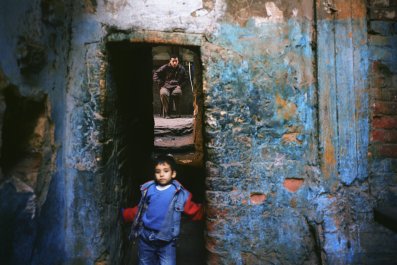

It's not hard to understand why a tribe like the Oglala Lakota would be interested in following Colorado and Washington. In January and February, Colorado collected over $6 million in tax revenue from recreational and medicinal marijuana markets. Pine Ridge is a sprawl of rolling Western wheatgrass prairie, ponderosa pine-fringed sand hills and wind-sculpted Badlands formations spread across a deeply rural corner of the fifth least populous state in the union. By far the largest employers are the federal and tribal governments. In Shannon County, which makes up the bulk of the reservation, over 47 percent of the population lives in poverty, according to the Census Bureau. That's the third-highest poverty rate in the country. In short, the tribe could use any economic boost it can get.

The votes in Washington and Colorado "showed us how the economic part of it—of recreational use—could help us," said Larry Eagle Bull, the Oglala Lakota tribal councilman who introduced the marijuana measure. "We want to get in on it while we can actually benefit."

If tribal governments have to wait for Congress to legalize marijuana, states would be free to pursue new avenues of revenue while tribes get "placed behind the eight ball," said Brandon Ecoffey, managing editor of Native Sun News and a member of the Oglala Lakota tribe. In a recen op-ed he envisioned tribal entrepreneurs establishing "campgrounds, coffee shops and automobile repair shops. Artisans will finally be able to sell their products at market value to the pot tourists that will travel from across the world."

"It's a job creator," Ecoffey told me. "For a tribe on a reservation like Pine Ridge—it's desolate, in the middle of nowhere—there aren't a lot of options for us. We have to think outside the box."

On a Friday in mid-March, I visited Big Bat's, a combination gas station–convenience store–fast-food restaurant that functions as a kind of village square for the reservation's largest town. Inside, Pauline Mills, a wizened woman in her mid-50s selling homemade earrings, said she would welcome increased tourism driven by marijuana sales.

A 20-minute drive away, at Wounded Knee—the site of an 1890 massacre of Lakota men, women and children by American soldiers—a young man named Daniel Blue Bird was selling dream catchers and bracelets to tourists near the hilltop mass grave that holds the massacre victims. Blue Bird sells his wares from a plywood-and-sheet-metal kiosk nearby or, on cold days, out of an SUV. He said increased tourism might allow him to set up a permanent shop. "That'd make a big difference. It'd be a lot better for me," he said, looking out at his kiosk, a small structure dwarfed by an expanse of dimpled prairie and yawning slate sky.

Others are skeptical of the economic viability of a marijuana market on Pine Ridge. "I don't think they'll be able to create a market, not a big one anyway," said Matthew Fletcher, a law professor at Michigan State University and editor of Turtle Talk, a prominent blog on Indian law and policy. "First, there's no money on the reservation. It can't sustain a market with just the local population, so you would need people to come in. But, secondly, a tribe that allows it to be free and easy to get marijuana is asking for trouble—a lot of political pushback and perhaps legal and prosecutorial pushback."

The campgrounds and coffee shops would have a hard time turning a profit, Fletcher said. "There's no money in that sort of thing. The economy is too small, unless you have a Coachella Festival there every couple of months or something."

Even with a large enough marijuana market, it's not clear that the Justice Department will extend to tribes the courtesy the Cole Memorandum extended to states.

"The Justice Department has yet to say how and under what circumstances it will regulate marijuana on Indian reservations," said Eid, who was the U.S. attorney for Colorado from 2006 to 2009. "Tribal leaders have been concerned about being singled out for enforcement. For a state to say wholesale it won't follow federal law—that's a pretty big move. You have to go back to the Civil War or the end of Prohibition. But tribes typically have small populations, even if their lands are large geographically, and they don't have the kind of political clout states have. There is a lot of fear over what the feds might do to make an example out of tribes if they get it wrong."

On Pine Ridge, supporters of legalization bristled at the notion that states might get to play by different rules than tribes. "Historically, Indians were always treated differently," Steele said. "But we're a sovereign nation. I understand federal law does apply here, but if you're going to hold us to it, you're going to hold every state to it."

Even if the Cole Memorandum is applied to the tribe, tribal officials would still need to implement the "strong and effective regulatory and enforcement systems" required by the memorandum to prevent, for example, sale to minors or "diversion"—the smuggling of marijuana to states where it remains illegal. "Tribes will have to come up with sophisticated regulatory mechanisms—that's the linchpin," Fletcher said.

Limited resources and geography pose barriers to creating those mechanisms on Pine Ridge. The tribe's budget allows for only 51 tribal police officers to cover an area almost three times the size of Rhode Island. Open country and dozens of roads cross reservation borders into South Dakota and Nebraska, where marijuana remains illegal.

The referendum would legalize marijuana only after the tribal council created an enforcement scheme. "It's not going to be the Wild West here," Eagle Bull said. "There will be regulations.… We'll get people to come here, or we'll travel to Denver to find out how they're doing it, what works best, what problems they have so we don't develop them."

Although the tribe voted last year to end over a century of near-continuous prohibition on the reservation, it has yet to develop regulations needed to formally legalize alcohol. Just south of the reservation, when I visited in March, somebody had modified a spray-painted tag that read "Legalize Alcohol" to read "Legalize Peji," a Lakota word used as slang for marijuana.

Supporters say that if the tribal council approves the referendum, it will pass handily. "I think it'll be a lot easier than the alcohol issue," said Steele. "I had traditional people against alcohol, but those same individuals are in favor of marijuana.… I haven't heard of any story where an individual overdosed on marijuana or died in a car accident on marijuana."

A predictor may be a 2010 ballot initiative to legalize medical marijuana in South Dakota. In Shannon County, the vote was almost 70 percent in favor of legalization. (Eagle Bull's referendum would include a medical-only option as well as a recreational option.) While Steele is less optimistic, Eagle Bull is confident that the tribal council will approve the referendum, after it delayed consideration in March.

"The fight was over gambling on the reservation, and that passed," Eagle Bull said. "This is just another step in the fight for our sovereignty. Plus, the U.S. is rethinking marijuana. It's the right time for us to try this."