In 1969, Honeywell tried to sell a Kitchen Computer, which was about as practical as a home nuclear reactor. It cost $10,600, weighed 100 pounds and came, the ad said, "complete with a two-week programming course" for Donna Reed–esque housewives who would then be able to punch its buttons and read recipe combinations off a teletype machine.

Food and data have had a love-hate relationship ever since. We really want to use data to gain deep insights into cooking and eating, and so far we have mostly failed at it. But a new era of bytes about bites is upon us. "We're at this interesting inflection point in big data and food," says Justin Massa, CEO of restaurant data startup Food Genius. "It's inevitable. It's going to happen. We're building the technology now, knowing the data is going to come."

Food data will mean a lot more than searching Yelp for a restaurant that doesn't suck or installing Quirky's Egg Minder so you can check a smartphone app when you're bored in a meeting and want to see how many eggs are left in your fridge.

We're going to know things we never knew we could know. Give it a couple of years and someone opening a restaurant will be able to tap data to determine the ideal menu to attract the right demographic in that neighborhood. And if the likely customers happen to be people who love both Zürcher Geschnetzeltes and Pad See Ew, a cross-analysis of data about human taste and food chemistry could suggest a house specialty no one ever thought of before, like Swiss Thai fusion asparagus quiche—a dish that an IBM computer recently created.

Food Genius is one sign of the innovations converging on food. The company, founded in 2010, is intent on scooping up as much data as possible about what we eat. It pulls menu items from 350,000 restaurants and has a deal to suck in the entire catalog of available items each quarter from online ordering company GrubHub. The data for the first time can be used to identify subtle trends in menu items and pricing, which Food Genius sells to the likes of Kraft and Applebee's. A couple of recent insights: Pesto is way more popular in California than anywhere else, and Philadelphia ZIP code 19131 has an off-the-charts attraction to sharp cheddar on burgers—eight times greater than the U.S. as a whole.

Restaurants, for the most part, have long been data dumb. Chains gather and analyze massive amounts of their own data, but they're usually myopic, failing to see beyond their corporate boundaries. Many of the 455,000 independent restaurants in the U.S. don't collect or analyze much data. "The people we talk to are excited to just get a digital menu board," Massa says. "They're not thinking as much about what happens next."

But starting now, data collection will ramp skyward. Restaurants will get savvy about gathering data while companies like Food Genius get more sophisticated about analyzing that data and cross-referencing it with chatter on social media, census information, location data from cell phones and so on. Massa says his company is less than 18 months away from being able to suggest the perfect menu for a specific street corner.

Over the past year, IBM has introduced another element in this food data equation. Ever since its Watson computer won on Jeopardy in 2011, IBM has been looking for ways to apply that technology in the real world. One of those efforts is dubbed "computational creativity," first aimed at cooking. By crunching millions of pages of information about global recipes, ingredients, food chemistry, aromas and the psychology of taste, Watson can have more raw knowledge about food than any chef could keep in his or her noggin. The computer can then suggest dishes so unusual—such as Turkish bruschetta with Japanese eggplant—they sound like Franken-recipes. As a test, IBM paired Watson with chefs in a food truck at South by Southwest in March, and some of the dishes seemed to impress the Austin festival's crowd.

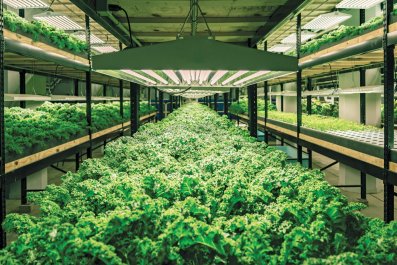

Chef Watson is still a science experiment, but computers are going to increasingly learn stuff about food that chefs never knew. A startup called PreciBake can monitor a bakery's processes and learn the details—from ingredients to oven temperature—that result in a perfect batch of croissants or cookies. The goal now is to improve efficiency at big bakeries, but PreciBake can also gather data to build models of baking. A chef could use the models to test ideas without ever turning on an oven.

Nobody is suggesting that kitchens in all the top Michelin restaurants will soon be manned by robot cooks tapping into supercomputer databases. ("Waiter, there's a flash drive in my soup!") Instead, creative chefs will get unprecedented tools.

For home cooks, food data will bring interesting new applications, such as the reverse recipe. Devices like the Egg Minder will no doubt proliferate, until your kitchen becomes smart and knows every item in your refrigerator and pantry. Then you won't have to look up a recipe and go shop for the ingredients. Your smart kitchen will tell an app—driven by Chef Watson–type data—what you've got to work with, and the app will spit out creative recipe possibilities. In my kitchen, that will probably be curried Brown 'N Serve with banana-infused Cap'n Crunch.

Massa has another vision, based on where Food Genius is heading. Today, if you feel like a good plate of chicken tikka masala, deciding how to get it can be a tedious process: You might look in your pantry to see if you can make it, look online to see if you can get it delivered or consider the nearby Indian restaurants. Massa envisions an app that would just ask what you want to eat; know what's in your smart kitchen; know all the surrounding menus and prices, plus things like current wait time for tables; and present your best options.

As big a role as food plays in our lives, we've been incredibly dumb about it. Fallible humans have been writing since 2007 that poutine is a growing trend. Food Genius data show that the heart-stopping Canadian plate of fries and cheese curd has never been on more than 1 percent of U.S. menus. Such knowledge is a start toward really understanding what we eat and why, and it beats having a 100-pound computer on your kitchen counter.