"Meet me in front of Cuchifritos on 116th Street in Spanish Harlem," texts Von Diaz. I arrive a few minutes early, and I'm pretty sure I'm in the wrong place. The window display in this takeout spot is filled with trays of fried chicken, fried plantains, fried balls of masa stuffed with spiced meat and fried bacalao (codfish fritters). This is Puerto Rican food, and frito (or "fried") is the operative word here.

I'm supposed to be meeting Diaz to talk about nueva (or new style) Puerto Rican cuisine, and this place looks about as old-style as you can get. "Don't freak out," Diaz tells me as we enter. "I just thought we'd start here and sample some traditional fried food."

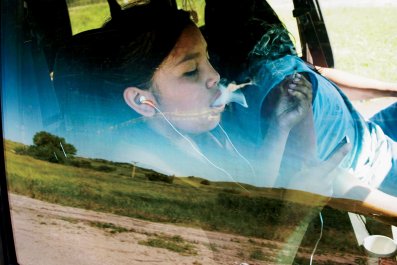

Diaz, 32, a Puerto Rican journalist who grew up in Atlanta, is obsessed with her native cuisine. Much like the story Julie Powell wrote about cooking her way through Julia Child's Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Diaz is working her way through a Puerto Rican classic. Cocina Criolla, by Carmen Valldejuli, a kind of Puerto Rican Joy of Cooking, is a thick cookbook that, according to Diaz, "every Puerto Rican owns." Looking for a way to help her understand Puerto Rican culture and her own identity, Diaz starting cooking from "the bible" several months ago. It's a sentimental project: following the well-worn, stain-splattered pages of her grandmother's copy of Cocina.

"Memories of my grandmother in her kitchen, peeling yucca in her flip-flops with her hair in rollers, came flooding back as I held the book in my hands, charmed by its ugly front cover with bad drawings of tropical fruit," writes Diaz in a multimedia blog series on the site Feet in 2 Worlds.

Diaz's grandmother, whom she calls Tata, is now living in Utah and battling Alzheimer's. Diaz misses her cooking and her stories, but as she fries surillitos (cigar-shaped fritters) and braises cow tongue, she is comforted by the memories of her childhood visits with her grandmother in Puerto Rico.

When I told Puerto Rican-born chef Carmen Gonzalez about Diaz's Julie/Julia/Von/Carmen experiment, she laughed. "Wow, I sure hope she has some friends who are carpenters, so they can make her doorway wider! That girl is going to gain some serious weight!" Gonzalez, who made her reputation on the television show Top Chef Masters and through her restaurants in Miami, New York and Portland, Maine, says, "I love that book. I grew up with it. We all did. But man, is that unhealthy food."

Diaz had no intention of changing jean sizes, so she decided to attack the book with a new focus. Her goal? Make Puerto Rican classics with a lighter, fresher and healthier touch.

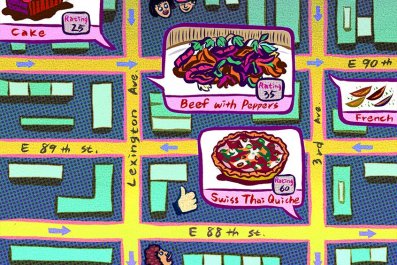

After we taste the fried stuff, we move on to a local bodega to shop for fresh chicken, chorizo, cilantro, avocados, mangoes and lemons. Diaz has invited me into her minuscule (but highly organized and efficient) kitchen in the Spanish Harlem apartment she shares with her partner, Marin. She puts on mellow Latin music, and we set out to work.

The first dish is pollo en agridulce, or sweet and sour chicken. In Valldejuli's original recipe, a whole chicken is smeared with a dried oregano/garlic paste and then browned in half a stick of butter. Diaz uses fresh oregano and fresh garlic and olive oil to make the paste, which she rubs under the chicken's skin. She decides to brown the bird using only two tablespoons of butter and a touch of olive oil. The chicken in the pot is surrounded by fresh chorizo sausage, brown sugar and a splash of vinegar. It braises on the stovetop for over an hour.

While the chicken simmers (and the apartment fills with a scent that is at once familiar and exotic), Diaz gets started on the ponque, or pound cake. That's "pound cake" as in one pound of butter. As it bakes, she makes a mango and orange coulis with fresh lemon zest. It is definitely not Puerto Rican, but Diaz feels the cake, and the meal, needs fresh fruit.

"Even though many have said that Puerto Rican cuisine lacks variety, that it's too fattening, I think it just hasn't been properly explored," explains Diaz. "Like most other cuisines developed in low-income areas—take Southern soul food, for example—popular dishes reflect what people have access to and can afford. In much the same way, Puerto Rican food really benefits from subtle augments, withdrawing some of the fat and brightening up the flavors with fresher ingredients. It's not really a matter of fusion. It's just good common sense."

A few hours later, we dive into the chicken. Instead of serving it with traditional (and heavy) rice and beans, Diaz brings to the table a green salad topped with avocado and hearts of palm. The chicken is bursting with the rich, delicious flavors of garlic, fresh herbs and spicy sausage, but it's also quite light. To end the meal, Diaz passes a plate of the pound cake — a moist, buttery cake that feels light and fresh when served with the smooth orange-colored mango sauce.

"I've used this project as an excuse to bring people together," she explains. "For those who didn't grow up around large Caribbean immigrant communities, the flavors are entirely new. And I haven't made a meal yet—with the exception of the beef tongue, which is, arguably, an acquired taste—that my friends didn't go gaga for."