Negotiators in Vienna trying to persuade Iran to give up its nuclear arms program are at an impasse and seem about to end with nothing resolved. That raises an important question for the West and for Iran's neighbors: Will a delay in the diplomacy advance Iran's mad dash to make a nuclear bomb?

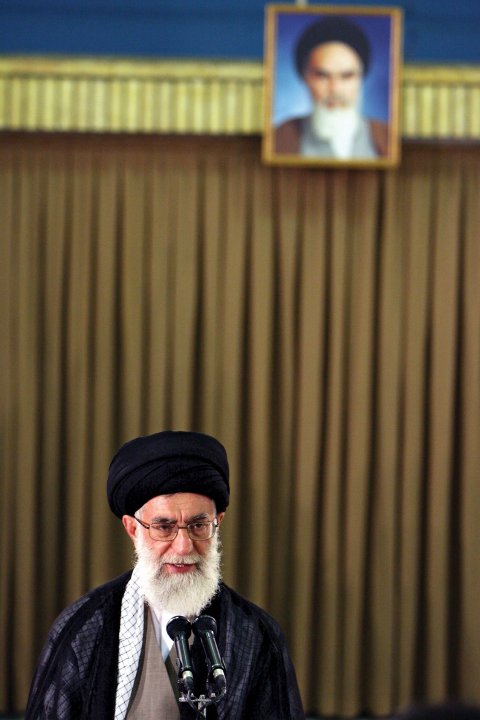

The world's top powers seem set to announce they have failed to reach an agreement with Tehran over its nuclear program by their self-imposed July 20 deadline and will soon announce that they intend to extend the talks for up to six months. Meanwhile, recent statements by Iran's supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, who is in charge of his country's nuclear program, suggest that Iran is reluctant to accept major limits on what it can and cannot do.

Over the weekend of July 5, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry arrived in Vienna to assess what chance there is of reaching a deal. He was joined by the foreign ministers of France, Britain and Germany, as well as representatives of China and Russia. (The five powers with permanent seats on the United Nations Security Council and Germany are known collectively as the P5+1.) Diplomats have been meeting with their Iranian counterparts in Vienna on and off for six months, trying to nail down a comprehensive agreement.

The absence at the weekend of the Russian and Chinese foreign ministers suggested a rift among the five powers, leaving Vienna watchers to wonder whether Kerry's arrival may indicate the opening of a separate bilateral diplomatic track between the U.S. and Iran. "There has been tangible progress on key issues," Kerry told reporters Tuesday, adding, "However there are very real gaps on other key issues."

According to a "joint plan of action" that the six powers signed with Iran in January, Iran will freeze parts of its nuclear program in exchange for the lifting of some of the economic sanctions imposed on it by the six powers. According to that pact, the two sides were to reach a final settlement in six months, with the option of a six-month extension.

Gary Samore, who was President Barack Obama's top adviser on nuclear proliferation from 2009 to 2013, said earlier this month that while the two sides are still far apart, neither wants to break the deal reached in January. "Therefore," he concluded, "an extension is likely."

On Tuesday, the Senate's foreign relations committee chairman, Robert Menendez (D-NJ), said that the U.S. "will need a deal that doesn't just freeze the clock on Iran's nuclear weapons programs, but a deal to demonstrable and verifiable action by Iran over years that in fact turns back the clock and makes the world a safer place."

One of the goals of the six powers is to prevent Iran from maintaining enough uranium-enriching centrifuges to produce the necessary fuel to quickly manufacture a nuclear bomb at the time of its choosing. But in his statement, Khamenei made clear that no such limits are acceptable to him.

"Their aim," Khamenei said on his website, referring to the P5+1 negotiators, "is 10,000 centrifuges of the older type that we already have," but "our officials say we need 190,000. Perhaps not today, but in two to five years, that is the country's absolute need."

According to Samore, while there has been some progress in recent talks on that "core issue"—how many centrifuges Iran can keep and of what type—"neither side appears to make any significant concession. Iran wants to have the ability to produce nuclear weapons on short notice, while the six world powers are not prepared to accept Iran as a nuclear threshold state," he said.

"Both sides are very constrained by domestic politics," added Samore, now with the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University. "President Obama can't sell a nuclear deal to Congress if it allows Iran to retain a credible nuclear weapons option. And President Rouhani cannot sell a nuclear deal to Supreme Leader Khamenei if it requires Iran to give up its nuclear weapons option."

Khamenei's statement—which caught Western diplomats in Vienna by surprise—showed that the two sides are even further apart than previously thought. Iran's supreme leader may have deliberately distanced himself publicly from his negotiators in Vienna to secure the support of his conservative political base.

Unlike the unelected Khamenei, the political future of Hassan Rouhani and his foreign minister, Javad Zarif, who leads the Iranian team in Vienna, depends on a successful outcome at the Vienna talks. They have promised that by talking to the West, Iran will gain much-needed relief from the sanctions that are crippling its economy. But that relief may prove elusive. Even critics of the January interim agreement agree that the proposed easing of sanctions has been severely limited. Nevertheless, two new studies suggest Iran's economy rebounded in 2014.

Meanwhile, Obama, who also has a lot at stake in ensuring a successful outcome in Vienna, faces not only mounting domestic pressure but deep skepticism from America's strongest allies in the Middle East. The Sunni Arab states, led by Saudi Arabia, and Israel have publicly expressed their disbelief that talks alone can halt Iran's advance toward a bomb.

Obama visited Riyadh in March in an apparently unsuccessful attempt to convince the Saudis that diplomacy was the right course. And on July 10, when speaking with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu about the deteriorating situation in Gaza, Obama also briefed him about the Vienna talks. Obama "reiterated that the United States will not accept any agreement that does not ensure that Iran's nuclear program is for exclusively peaceful purposes," said a White House statement summarizing the phone call.

The chief American negotiator in Vienna, Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs Wendy Sherman, has spent a great deal of time recently on Capitol Hill and in Jerusalem trying to counter criticism of the talks. One of her talking points has been that even if Iran maintains some nuclear capabilities, strong international inspection will be built into any agreement to ensure that Iran cannot become a military nuclear power.

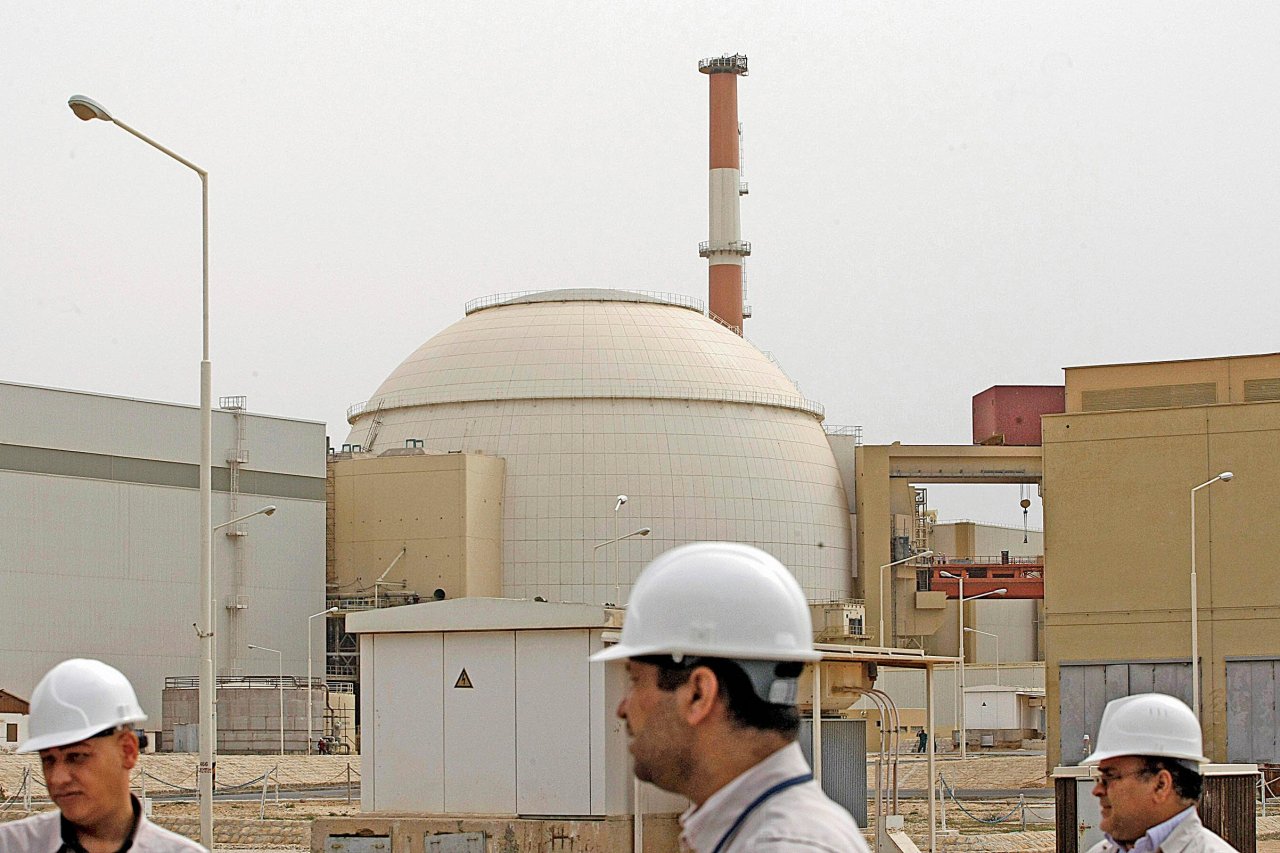

Critics note, however, that while inspectors of the Vienna-based International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) may be able to monitor openly declared nuclear facilities, Iran has a long history of hiding elements of its nuclear program. Iran did not acknowledge its introduction of a new generation of centrifuges, known as P2, until it became public in 2004. Also, Iran only admitted to building a deeply dug enrichment facility at Qom in 2009 after it was discovered by Western intelligence agencies.

"So the question is, Is everything now on the table?" says former IAEA deputy chief Olli Heinonen, now at the Belfer Center. "Has Iran declared everything? Or is there still something the international community doesn't know?" Until Iran accounts for all its past activities, he said, "I think the concerns will not go away."

Iran's habit of cheating was the basis for the six Security Council resolutions that imposed sanctions on the country. "The whole case against Iran hinged on these violations" of its obligations under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, says Emily Landau, who heads the arms control program at the Institute for National Security Studies, a Tel Aviv University think tank.

The provisional Vienna agreement in January already allows Iran to maintain its low-level uranium enrichment capabilities, even though the U.N. Security Council resolutions called for the suspension of all enrichment, Landau notes. "The interim agreement now has a life of its own, and that in itself changes the dynamics of the talks," she said.

If a "bad deal" is reached, she adds, both sides will have an incentive to prop it up, so the West will likely "look away" if Iran violates any of its strictures. Meanwhile, she said, an extension of the Vienna timetable will significantly change how the talks are conducted.

A growing fear of those closely watching the Vienna talks is that a six-month extension would allow Iran to further advance its nuclear program while the West's attention is directed toward the violence in Ukraine, Syria and Iraq and drifts further away from the dangers of nuclear weapons proliferation that Iran poses. Kicking this can down the road could make the world a far more dangerous place.