According to nearly nine out of 10 Russians, 2014 has been a great year for their country. In the wake of the annexation of the Crimea in March, Russians have been riding high on a wave of patriotism, nostalgia and triumphalism. President Vladimir Putin's approval ratings have climbed to a whopping 86%, even as Russian State TV whips up almost Soviet levels of xenophobia and hatred of the United States. In the meantime Russia's security forces are having a field day rolling back the internet and civil society. The Duma, backed by the Russian Orthodox Church, has been busy churning out ultra-conservative legislation on everything from banning bad language in films and plays to regulating women's high-heeled shoes – which in the opinion of some Duma members are bad for fertility.

But what comes next? As the famously sober Putin perhaps doesn't know, after every party comes a hangover. On the face of it, the US and EU's limited sanctions on more than 100 Putin cronies and 20 companies associated with them haven't done much direct harm. The Kremlin has also shrugged off the Group of Eight's suspension of Russia's membership – in fact, it may even have helped to boost Putin's popularity.

"The feeling of isolation has driven the population to believe that no one in the West loves us," says Alexei Grazhdankin, deputy head of the Moscow-based Levada polling group. "So there's nothing left to do but rely on the current leadership." But in truth, the real cost of Crimea could be the economic prosperity which has been the cornerstone of Putin's 14-year hold on power.

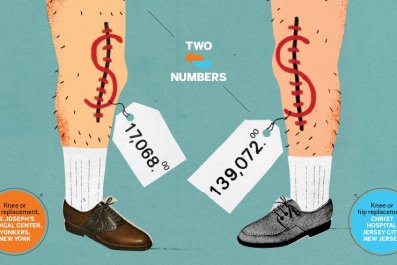

First and foremost, sanctions have scared foreign direct investors and, much more damagingly, international capital from coming to Russia. Since the annexation of Crimea, Russian companies have found it all but impossible to raise money abroad. The first six months of the year saw syndicated loans for Russian commodities producers plummet 82% to $3.5 billion compared to the same period in 2013. Bond sales by Russian companies also fell through the floor, from $19 billion for March to May last year to less than $2 billion this year. As a result, Russian banks and companies have turned to Sberbank, VTB and other domestic lenders – and ultimately Russia's Central Bank itself – to meet their combined $191 billion of foreign debt payments due this year. Putin's trusted economic aide Elvira Nabiullina, now chairman of the Central Bank, has had to double financing for commercial lenders to more than $142 billion in April this year alone.

The Kremlin's response? To blame meddling foreigners and claim that Russia can proudly go it alone. "Both the authorities and the public have interpreted every serious crisis in the world's major economies in the last 30 years as the result of foreign influences, not as a result of domestic policy," according to Vladislav Inozemtsev, a professor of economics and director of the Moscow-based Center for Post-Industrial Studies. "Russian authorities in recent years have been so successful in convincing its citizens that all evil comes from the outside that they may have become convinced of it themselves."

Yet at the same time, Russians with cash are sending it offshore in unprecedented quantities. "The business class [is] terrified about the potential further expansion of sanctions," says Professor Mark Galeotti of New York University. "But it's not something they can yet publicly articulate – or at least they don't feel comfortable doing so." Instead, they're voting with their pocket books. According to the Central Bank, capital flight from Russia hit $75 billion in the first half of the year – more than twice 2013 levels – as investors and ordinary Russians ditched the ruble en masse. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have estimated total capital flight this year will top $100 billion.

True, after a decade and a half of sky-high energy prices, Russia has deep pockets: its sovereign Reserve Fund and the National Wealth Fund stand at $87 billion each. But already the post-Crimea cash crunch is forcing the Kremlin to dig into those pockets. Last month Russia's finance minister announced that part of the State Pension Fund would be invested in infrastructure projects in Crimea – including a $4.3 billion bridge over the Kerch Strait to link the peninsula to Russia proper – and the Duma voted to allow Welfare Fund to cover losses at the state-owned VEB Bank over the Sochi Olympics.

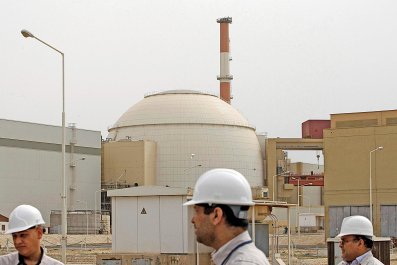

But Putin's – and Russia's – problems go much deeper than just cash-flow. Putin's reaction to an economic slowdown has been to boost state monopolies in the oil and gas sectors – patriotically dubbed "national champions" – at the expense of entrepreneurship. For all Putin's talk of modernising the economy, Russia remains, at base, a petro-state with nuclear weapons. Export duties on oil and gas account for 49.4% of the Kremlin's federal revenues. Since Putin came to power in 1999 state enterprises' share of the economy have risen from 30% to over 50%, according to a recent study by BNP Paribas. At the same time the swollen bureaucracy and security apparatus sent Russia plunging down Transparency International's corruption rankings from 82nd in 2000 to 127th today – joint with Pakistan and Nicaragua. The current crisis will only deepen that reliance on natural resources.

"The measures the president is proposing will certainly limit competition and freeze modernisation," Alexei Kudrin, a Putin adviser who served as Russia's Finance Minister for more than a decade, told Bloomberg recently. "They will lead to an increase in market regulation and protectionism."

Already, the hidden costs of Crimea are starting to hit Russia where it hurts the most – in the oil and gas sector. In June UK-based HSBC and Lloyds withdrew from a $2 billion trade finance deal between BP and Rosneft, Russia's largest oil producer, whose CEO Igor Sechin, has been blacklisted by the US for his role in Crimea's annexation. Financing for Gazprom's ambitious $38 billion South Stream project, designed to pipe Russian gas to the Balkans along the floor of the Black Sea, has also run into difficulty – as well as political opposition from the EU which has asked Bulgaria to suspend work on their section of the pipeline on the grounds that Gazprom's control of the pipes violates EU regulations. Ukrainian Prime Minister Arseniy Yatseniuk has lobbied vigorously for Brussels to declare the entire project illegal. "South Stream aims to increase Europe's dependence on [Russian] energy, remove Ukraine as a transit country and increase Gazprom's influence in Europe," Yatseniuk said recently. "We call on the EU to block South Stream altogether."

Annexing Crimea has certainly made Russia poorer. But has it at least made it safer? Many commentators – for instance Ukrainian TV's Savik Shuster, who called Putin "Europe's new Hitler" – have presented Putin's Crimea adventure as an exercise in imperial ambition and confidence. But the evidence points the opposite way – that Putin invaded Crimea out of fear and defensiveness, to keep Sevastopol out of Nato's hands and recover at least some influence in Kiev after the utter failure of Viktor Yanukovych to win support for his pro-Russian policies. Yet the end result of the Crimean annexation and of the low-intensity insurgency that Russia is quietly fuelling has been to push Ukraine closer to Nato and the EU. For sure, Sevastopol will now never be a Nato base. But Russia has grudgingly acknowledged the legitimacy of Petro Poroshenko's election as president of Ukraine, and has been unable to prevent him from signing an association agreement with Brussels. Ukraine is now set on an inexorably westward path (though even Poroshenko makes clear that doesn't include Nato membership). As far as Ukraine goes, Russia has reached a kind of bloody stalemate: the mouse lost its tail, but ended up escaping westwards, ultimately, to a place of greater safety.

Which is more than can be said for Russia. Among the patriotic giddiness, there are signs that Putin's praetorians are beginning to attack each other in the quest for power and money. It's a replay of security-service clan wars that have periodically surfaced as police and spooks compete for ever larger chunks of Russia's economy.

In June Major-General Boris Kolesnikov, deputy chief of the Interior Ministry's directorate for commercial crimes and anti-corruption apparently managed to push past two police guards and leap to his death out of a sixth floor window. He and his boss had been charged with entrapment, bribe-taking and racketeering. But according to Mark Galeotti, an expert on Russia's security apparatus, Kolesnikov's department "is not only a potentially powerful political asset – whoever controls economic crime investigations is especially useful to the Kremlin – but also a lucrative source of revenue" because police who uncovered evidence of corruption demanded large bribes for their silence – or used the information to steal multi-million dollar businesses.

Putin will doubtless rein in his feuding spooks. But he faces a far more fundamental problem: the economic cost of Crimea threatens the social contract that has been the base of his power. Russians so far have been happy to surrender liberty in exchange for prosperity. But as the country slides towards recession – with the IMF predicting economic growth of less than 1% – Russia is more isolated and economically precarious than at any previous point in Putin's tenure.

"The first alarm signals will sound when it will be too late to react," predicts Inozemtsev. "We will probably see a repetition of the dramatic events of the late 1980s – of course, this may not happen for a while." For the time being, Russia's cash reserves and the high price of commodities will buoy up Putin's illusion of power. But the triumphal year of 2014 is more likely to go down in history as the point where Putin's patriotic dream collided with harsh economic reality.