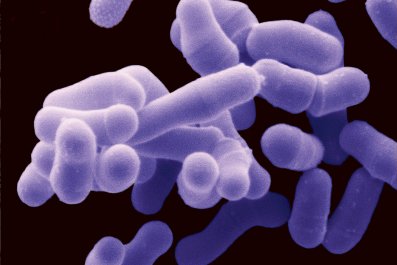

Humans are at constant war against bacteria, and the increasing prevalence of drug-resistant strains has fueled fears that one day soon we may lose the fight completely. Researchers from Hebrew University of Jerusalem may help us once again gain the upper hand: Michael Brandwein and his mentor, Doron Steinberg, have developed a technology capable (to extend the battlefield metaphor) of cutting the lines of communication between bacteria—and therefore rendering them ineffective.

In nature, most bacteria are associated in biofilms, unique living environments that harbor the microorganisms and encourage them to grow—and attack other living things. Biofilms, which cling to both organic and nonorganic surfaces, are better known to you and me as the slime often seen on recently fresh fruits and drainage pipes. To stop biofilms from forming, Brandwein has created a sprayable polymer containing a small but powerful molecule named "TZD." When applied to food packaging, the spray prevents bacteria from communicating with each other. "They don't know to grow and form a biofilm. It keeps them static instead of killing," Brandwein says. "One bacterium isn't able to do anything; they need each other to coordinate their attack." Without biofilms, food has a longer shelf life and is far less likely to cause illness in consumers.

Food packaging is only one of many uses developers see for this anti-biofilm polymer. "Biofilms are basically everywhere, mostly causing problems," explains Steinberg. His team is working on a coating for urinary catheters and an oral anti-cavity anti-plaque product. The team is also developing a way to keep biofilms from growing on the bottom of ships. Here "it is an economic problem, not a health one," he says, as biofilms can slow down the ships.

The best part is that this approach helps buck the trend of overusing antibiotics. Unlike the case with drugs, the spray's potency is not at the mercy of evolution. "Bacteria need to communicate in order to be effective and cause disease; no bacteria is going to want to develop a mechanism to stop them from communicating," says Brandwein. As for being an alternative to antibiotics, it may be too soon to speculate, but according to Brandwein, "it shows promise that this is where it's headed."