Bang.

A youth lies on the ground between desks and bloody textbooks. A brunette in an argyle sweater is sprawled nearby on the linoleum floor, with a red hole in her abdomen.

We are just 10 miles from Newtown, Connecticut, the site of a mass shooting of schoolchildren in 2012, and Phil Chalmers has 600 high school students riveted with a PowerPoint presentation featuring photos of murdered and maimed teens.

"First, he killed his teacher. She died with chalk and eraser in her hand, doing what she loves to do. Bang!" Next slide.

On a Tuesday in early June, America's self-proclaimed "Leading Authority on Juvenile Homicide and Juvenile Mass Murder" is telling in graphic detail the story of Barry Loukaitis—who in 1996 shot three people to death and injured another at Frontier Middle School in Moses Lake, Washington—as part of his popular anti-violence presentation. Chalmers tells his audience that Loukaitis came to Frontier looking for the kids who had teased him, so "be careful who you're bullying, because you could be bullying a potential mass murderer."

With his sandy blond crew cut and mixed martial arts T-shirts, Chalmers looks like an undercover cop posing as a gym coach, but he runs a ReMax real estate agency in Aurora, Ohio, and despite having given these presentations for 30 years, he has not been employed in either a police department or a district attorney's office, nor has he studied criminal justice in school. He never took speech training either, but after becoming a Christian as a teen, he took to the pulpit, warning church youth groups about the dangers of rock music, among other things.

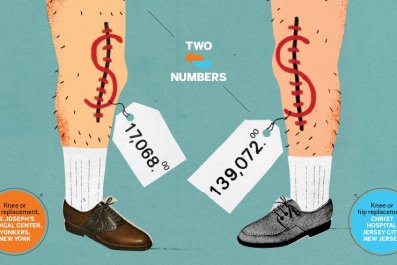

Chalmers might be the most popular motivational and anti-violence speaker on the circuit. He annually gives between 50 and 150 speeches to schools and law enforcement agencies for up to $3,500 per gig. For approximately $2,000 total, which includes a training weekend in Ohio plus a $1,495 annual fee, you can join his Sudden Impact Speaking Team. The almost 40 team members who have signed up can make speeches like Chalmers's and sell his merchandise, such as T-shirts and DVDs.

Since the 2009 publication ofInside the Mind of a Teen Killer, a book published by the HarperCollins Christian imprint Thomas Nelson in which he claims to identify the 10 reasons kids kill, as well as warning signs—claims that several experts emphatically dispute—he has also fashioned himself into what he calls a "TV personality." He has served as the consultant and on-screen expert in the Biography Channel special Killer Teens and E's Billionaire Crime Scenes.

Chalmers also says he is in talks with a "major television network" about producing an Intervention-style reality show. He would introduce would-be killers—those who meet his criteria for homicidal risk—to incarcerated teen killers. The prisoners would then talk some sense into the troubled, but not yet homicidal, kids.

"The tentative title is The Teen Killer Whisperer," Chalmers says. "It's kind of funny."

(Chalmers asked that the network not be named, and a representative for the network did not comment at press time.)

"We're also pitching a book right now called See Spot Die," he continues. "It's on the connection between animal cruelty and homicide."

Chalmers says his work has helped law enforcement avert many crimes, though he did not specify how many cases he was directly involved in. Without explaining how he gets the number, he says, "We've stopped over 200 school massacres since Columbine. Probably more."

Bullies Pulpit

In the parking lot of the Outback Steakhouse near Newtown, there's a yellow Hummer with the word "BULLYPROOF" painted on the windshield in yellow, with squiggles suggesting bullet holes.

I recognize Chalmers's truck from the home page of his website. In the photo, Chalmers stands before the square vehicle with his legs apart, hands on his hips, wearing combat boots and dog tags. Other posted photos show him grinning alongside Dog the Bounty Hunter, Chris Hansen of NBC Dateline "To Catch a Predator" fame, Jessica Simpson, and serial killer David "Son of Sam" Berkowitz.

I met with Chalmers and his second wife, Wendi, the evening before he spoke near Newtown, to learn how he became America's "Leading Authority on Juvenile Homicide and Juvenile Mass Murder." He looked just like his website picture.

"We did some sightseeing in Newtown before we got here," Phil says. "We drove by Adam Lanza's mom's house." Chalmers opens his iPhone and shows me a picture: There he is, hands on hips, in front the of the white house where the former schoolteacher lived with her murderous son. He and Wendi even ate at an Italian restaurant that Nancy Lanza frequented, they tell me.

"We asked the waiter what she was like," Phil says. "She was apparently a very generous tipper."

Chalmers then launches into his backstory. He grew up poor in a dangerous part of Cleveland. His father was an abusive alcoholic. Around age 10, things started to turn around. Phil's dad stopped drinking. The family moved to Aurora, near Ohio's Amish country. The dirty, crime-filled streets he knew as a kid were replaced by suburban roads. He says he got good grades in high school and a spot on the football team. But he smoked pot and drank too much with his pals.

"We didn't commit any crimes," he says with a pained look. "We were just doing some things we shouldn't have been doing."

After graduating from high school, Chalmers was working in his town's public works department when a buddy there suggested that he come to his church. Several months after that first service, "the lightbulb went off," Chalmers says between creamy spoonfuls of soup. "I realized the things I was involved with were very empty."

Chalmers says he started speaking to Christian church youth groups to warn them about rock music. He says he once loved rock, but believed music led him toward a "bad choice of friends. I just started speaking on things that I felt influenced kids. Then it kind of took off into talking more about destructive decisions, sex and drugs."

When he was about 20, Chalmers interviewed his first teen killer, Sean Sellers. In 1986 the Oklahoma City 16-year-old killed his mother and stepfather while they slept and later claimed he'd been possessed by demons. Chalmers first saw Sellers on Geraldo; he wrote to the prison and asked for a meeting. The facility agreed. Chalmers told a youth organization with whom he worked about the meeting. The group put him in contact with a camera crew, which filmed the interview. This became Stuck in a Nightmare, a 1990 documentary about the alleged dangers of satanism released by the now-defunct Gospel Films Inc. (Sellers was executed for the murders in 1999.)

Chalmers says he was "was hooked" and began speaking with every teen killer he could find. He claims to have now spoken to 200 juvenile murderers and studied the cases of another thousand over the years. "That's why nobody else has done this," he says of his work, adding that a project of this scope "takes 25 years."

And why him? "Basically, I could speak their language. It's kind of a gift."

Among the questions he asks those who agree to meet, write or talk to him on the phone are "Did you masturbate? Did you wet the bed? Did you have sex with your sister?"

What he learned became the basis for Inside the Mind of a Teen Killer. In the book, Chalmers argues that kids kill for 10 reasons: an abusive home life and bullying; violent entertainment and pornography; anger, depression and suicide; drug and alcohol abuse; cults and gangs; easy access to and fascination with deadly weapons; peer pressure; poverty and a criminal lifestyle; lack of spiritual guidance and appropriate discipline; and mental illness and brain injuries. He also categorizes the six types of killer youth: "the family killer, the school shooter, the crime killer, the gang/cult killer, the baby killer and the thrill killer."

While Chalmers allows that violent media alone don't make teens kill (that claim has been debunked), he believes they contribute significantly to teen criminality. "It's the No. 2 cause on my list, so it's very important," he says. "The thing that people get confused about, they'll rant and say, 'You can't blame violent video games.' I kind of agree with them, yes and no. It's not one cause, but most of these kids have three to six causes. I don't meet a lot of mass murderers who like Taylor Swift."

Satan Is Real

Chalmers's presentation at Masuk High School in Monroe, Connecticut, was secular, but there's no denying an ideological overlap between his pulpit past and his current crime beat. In both Inside the Mind of a Teen Killer and his 2001 guide to pop music for Christian parents, I Don't Listen to the Lyrics, he espouses the same apocalyptic worldview. For example, in I Don't Listen to the Lyrics, he doesn't just slam the usual suspects such as Marilyn Manson, saying that his lyrics reflect "his hate for God and Christians." Chalmers also warns that "brutal and senseless violence, illicit and perverted sex, drug and alcohol abuse, gang activity, satanic ritual—are all part of our culture today.… We're in the last days, and the enemy, Satan, is pouring his spirit out upon men on the Earth." Likewise, in Inside the Mind of a Teen Killer, he warns, "The environment surrounding our children is becoming increasingly violent and as a result, so are our children." He emphatically points out that Luke Woodham, the Pearl, Mississippi, school shooter who killed three people in 1997, was in a satanic cult.

"I call this Generation Death. They see so much violence—they're very desensitized to it," he says by way of validating his use of gory photos and apocalyptic warnings. "If we don't keep it edgy—if I just get up there and say, 'Don't bully. It's bad,' I might as well just stay in Ohio."

Chalmers's in-your-face approach has nevertheless drawn ire from parents who think it might be too violent for kids. After a recent school presentation to 11- to 14-year-olds near Omaha, Nebraska, in which photos of dead children featured prominently, a parent decried Chalmers's style as traumatic, according to the area's NBC affiliate, writing to him that "your graphic violence is its own form of bullying. This sends kids to a dark place, one they may have never gone to.… I am so disappointed at our school for allowing you in the building."

Chalmers also talks about purity in his road show, often beginning his hourlong talk by warning young girls about sexual promiscuity—and comparing them to cars. "I talk to the girls about self-esteem. You're either cheap or you're classy, a pickup truck or a Lamborghini, and they get a kick out of that," he says. "That's a favorite of kids. They'll walk out saying, 'I'm a Lamborghini!'" He insists there's a connection between dressing sexy and becoming a victim.

Chalmers's approach was also off-putting to some during his anti-rock days. At least one theologian worried that he was presenting himself as an expert in Christian ethics without formal theological training, while he ramped up the aura of authority by traveling in a flashy tour bus or R.V., with a large entourage. Tony Jones, a progressive theologian who debated Chalmers on youth leadership panels in the early 2000s, says Chalmers faxed a weekly music newsletter to paid subscribers, in which he would review new pop music and explain why it wasn't Christian.

"It was always concerning to me, back in the day, that he had the strength to listen to Eminem, but that all the people who read his newsletter did not have the strength," Jones says. "I got the impression that he was a snake oil salesman. He seemed to me like a bit of an opportunist."

After Chalmers's presentation in Connecticut, Steve Ballok, who runs a local philanthropic organization, wrote a letter to the editor in the Monroe Courier, saying it was a "misuse" of funds intended for gun safety and possibly too religious for a public school. "Along with being a self-proclaimed authority on juvenile homicide, Chalmers is also a self-promoting merchandising profiteer. His website focuses on the promotion and sale of his DVDs, books and his for fee lectures.… Watching segments of the 'True Lies' program online had me agreeing with how one critic described it as being a 'soft core version of the scared straight program.' It also had me wondering, is this the right approach for Monroe Schools? Most of this program's traction is found in southern states."

What Makes an Expert?

Some of the country's top experts on teen violence tell Newsweek that Chalmers's methodology is flawed. They contend that you can't profile juvenile teen killers the way Chalmers has, much less make blanket statements about preventing shootings.

Laurence Steinberg, a distinguished professor of psychology at Temple University who worked as director of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Adolescent Development and Juvenile Justice, says that making data-based conclusions and predictions on behavior requires a large sample, and there aren't enough teen killers for a sufficient sample group. "There may be lots of factors that kids who have committed homicide share in common," Steinberg says, but "there are probably millions of people who have those factors who haven't committed homicide."

Chalmers's views also appear at odds with FBI guidelines on school shooters. In the first chapter of an FBI risk-measurement manual called "The School Shooter: A THREAT ASSESSMENT Perspective," an introduction warns that the publication is "not a 'profile' of the school shooter or a checklist of danger signs pointing to the next adolescent who will bring lethal violence to a school. Those things do not exist.'"

Asked about this criticism, Chalmers stands by his methods and pedigree. "I'm able to test my research and it works—it's like math," he says. "A lot of people have asked me, 'What did you take in school for this?' You can't take anything in school for this. It's hard work."

"He probably would have become a cop," says Wendi, who met Chalmers at a school in Missouri where she was a principal.

Chalmers sips his soda reflectively. "The truth is, if I were to have become a cop, I wouldn't have done what I've done because I would have been too busy working as a cop."

Chalmers has his supporters, including prominent law enforcement officials and one of the country's foremost anti-violence trainers. Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, an Army Ranger who taught psychology at West Point and is internationally recognized as an expert in violent crime and aggression, says Chalmers is "without a doubt, the definitive expert on teen killers."

"He's surveyed them all, he's corresponded with them all," adds Grossman, who runs the Killology Research Group, which teaches law enforcement agencies about violence and aggression. "He really knows his stuff."

Grossman dismisses the scholarly criticism. "The academic world is very insular," he says. "Very few people in that community move outside that community."

And Chalmers is very good at relating to the public. That day in Monroe, he captivated an audience of social-media-addled young adults; nobody in the room seemed to text, tweet or post on Facebook the entire time he spoke. Kids came up to him after the presentation for hugs and posed with him for pictures. School administrators and resource officers were equally rapt. One police officer from a neighboring department came to the school from another jurisdiction just to see Chalmers—he'd heard him speak at prior trainings and has been smitten with his message ever since.

Indeed, a large part of Chalmers's appeal is that he comes across as a minister in the truest sense of the term, and that's what his audiences seem to want: He truly attends to the needs of his audience. He tells students, teachers and first responders, who likely live in constant fear of school shootings, what they want to hear—with one quick presentation, they can prevent that which is largely unpreventable.

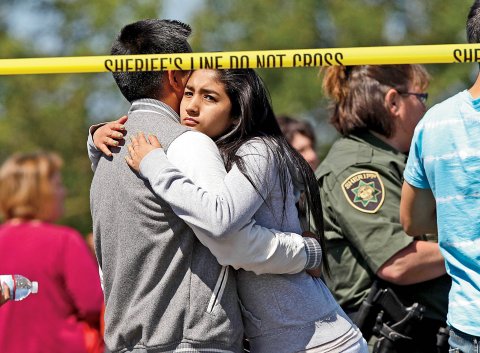

One 18-year-old sitting in the school cafeteria after Chalmers's presentation was initially skeptical. But she clicked when he started showing photos of school shootings. Like many at Masuk, this college-bound senior lives close to Newtown, where on December 14, 2012, Adam Lanza killed 26 at Sandy Hook Elementary School and then himself, after executing his mother at their home. She says adults in the area have avoided discussing Newtown with their children. So two years later, the massacre still felt like an open wound—until Chalmers showed up, she says.

"When I heard what it was about, I was like, 'We've heard this same thing over and over—lame,'" she tells me, looking up from her homework. "He showed us real pictures, [our parents] would never actually do that. I think we really needed to see it.

"This was the first time that we really talked about it in depth," she says. "It was more, like, closure."