The old railroad track, now a bike and jogging path, winds through the forest that separates Camp Lejeune from Highway 24, which caters to the thousands of Marines stationed here with cheap barbershops that will trim your high-and-tight for $5, furniture stores for the many young families on base, a couple of gun shops, a few bars and the requisite jiggle joint. None of this familiarly shabby Americana is even remotely visible from the verdant path. Trees crowd the sylvan trail like overeager children at a Fourth of July parade, their branches poking through the base's barbed wire fence. You hear far more woodpeckers and thrushes than Osprey helicopters. Spend enough time on this lush greenway or on the dunes of nearby Onslow Beach and you might forget that Camp Lejeune may be, as Dan Rather once said, "the worst example of water contamination this country has ever seen."

Camp Lejeune, in Jacksonville, North Carolina, is a toxic paradox, a place where young men and women were poisoned while in the service of their nation. They swore to defend this land, and the land made them sick. And there are hundreds of Camp Lejeunes across the country, military sites contaminated with all manner of pollutants, from chemical weapon graveyards to vast groundwater deposits of gasoline. Soldiers know they might be felled by a sniper's bullet in Baghdad or a roadside bomb in the gullies of Afghanistan. They might even expect it. But waterborne carcinogens are not an enemy whose ambush they prepare for.

That toxic enemy is far more prevalent than most American suspect, not to mention far more intractable. That the Department of Defense is the world's worst polluter is a refrain one often hears from environmentalists, who have long-standing, unsurprising gripes with the military-industrial complex. But politics aside, the greenies have a convincing point. Dive into the numbers, as I did, and the Pentagon starts to make Koch Industries look like an organic farm.

In size alone, the Department of Defense dwarfs the footprint of any corporation: 4,127 installations spread across 19 million acres of American soil. Maureen Sullivan, who heads the Pentagon's environmental programs, told me her office must contend with 39,000 contaminated sites (to be fair, a single base can have several, some as small as a single building).

Camp Lejeune is one of the Department of Defense's 141 Superfund sites; that's about 10 percent of all Superfund sites, easily topping any other polluter. And if the definition is broadened out beyond proprietary Pentagon installations, then about 900 of the 1,200 or so Superfund sites in the United States are "abandoned military facilities or facilities that produced materials and products for or otherwise supported military needs," according to a presidential panel on cancer.

"Almost every military site in this country is seriously contaminated," said John D. Dingell, a soon-to-retire Michigan congressman who served in World War II. "Lejeune is one of many."

These military sites form a sort of toxic archipelago across the land: Kelly Air Force Base in Texas, where the Air Force allegedly dumped trichloroethylene (TCE) into the soil, part of what some residents call a "toxic triangle" in south-central Texas; McClellan Air Force Base near Sacramento, California, which includes not only fuel plumes and industrial solvents but also radioactive waste; Umatilla Chemical Depot in the plains of northern Oregon, where mustard gas and VX nerve gas were stored; Rocky Mountain Arsenal, a onetime sarin stockpile just north of Denver; the Massachusetts Military Reservation on Cape Cod, poisoned by explosives and perchlorate, a rocket fuel component that is emerging as a major Pentagon pollutant. But because Camp Lejeune's abuses and betrayals are more flagrant, it has become a test case for whether the military can defend our soil without ruining it.

To those who suffered at Camp Lejeune, an ugly truth about the American military has revealed itself, a truth no amount of compensation or self-flagellation can vanquish. "I would never recommend to anyone that they go into the Marine Corps," said former Marine corporal Peter Devereaux, who has good reason to believe that his breast cancer is the result of drinking Camp Lejeune's tainted water. The Marines, he said, "are like a mafia."

As I was finishing this article, one of the Camp Lejeune activists I'd been speaking to sent me a short, sad email. "So much for our environment," the brief note said, linking to a Supreme Court ruling that was published that morning, June 9. The case, CTS Corporation v. Waldburger, called into question how long defendants in North Carolina had to sue industry for sickness or death caused by pollution. By ruling for CTS, the polluter, the Supremes indirectly but incontrovertibly complicated the efforts of those seeking compensation at Camp Lejeune. The fight, always hard, suddenly got harder.

Methyl-Ethyl Death

Among those who could never again be charmed again by Camp Lejeune's bucolic seaside surroundings is Jerry Ensminger, who today lives in nearby White Lake, North Carolina. Ensminger joined the Marines during the Vietnam War, in which his brother had been wounded. After a stint in Okinawa, he was assigned to Camp Lejeune in 1973. He and his wife lived in a housing complex on the base's northern edge. Their second daughter, Janey, was born in 1976. Photographs show a pretty girl with bangs and cheeks like apples. In one picture, she clenches her teeth and proudly shows off invisible biceps, in what looks like an imitation of her ball-busting drill instructor of a father.

But then, no more happy pictures. At the age of 6, Janey was diagnosed with leukemia. In the photographs that follow, her hair is cut short. Deposits of fat, from treatments, pad her body. You can see that she knows things no child should have to know. On September 24, 1985, Janey Ensminger died. She was 9.

There were many Janeys at Lejeune, and some didn't even make it through their first year of life. As Mike Magner writes in A Trust Betrayed, his masterfully thorough book on Camp Lejeune, the base hosted a grim dance of miscarriages, stillbirths and inexplicable postnatal deaths, especially during the 1960s and '70s: Christopher Townsend, dead at 3½ months from a legion of ailments; Michelle McLaughlin, dead at birth; Eileen Marie Stasiak, dead in the womb. Ricky Gagnoni, alive but a single month, started to bleed from his mouth as his mother fed him and died the next day. So many infants perished at Camp Lejeune that a nearby cemetery had a section mourning parents named "Baby Heaven[1] [2] ."

Finding no other answers, grieving parents turned the loaded gun of guilt upon themselves. "I blamed myself for years," a mother named Mary Freshwater would later testify. "I hated myself, I hated my body, 'cause I thought I had failed my children." Standing at a podium, unable or unwilling to hide her tears, she held up the pajamas her infant son was wearing when he died. She had never washed the vomit he'd left on them. She said that after his death, her doctors urged her and her husband to try again. They did. And their next son died, too.

"I have two graves out in Onslow Memorial Park," Freshwater said.

Those with plots at Baby Heaven now know that, as early as 1981, officials at the base were told that the millions of gallons of drinking water consumed by the base's 100,000 or so residents each day were full of what toxicologists call "methyl-ethyl death," informal shorthand for a variety of known and suspected carcinogens. But the first batch of groundwater wells was not shut down until the fall of 1984 and the winter of 1985. The base became a Superfund site in 1989, but even today, the full extent of the camp's contamination is not known. Blame that on poor record-keeping, stonewalling, arrogance or just plain ignorance. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) isn't even sure how many people have been poisoned by Camp Lejeune's bad water, though estimates suggest that it was consumed by as many as a million people.

How much the likes of Ensminger deserve in financial compensation for their grief is the most complex question of all: Suffering at once yearns for a dollar amount and resists such crass calculation. Ensminger is one of about 3,500 people involved in litigation against the Department of Defense. They thought the Marine Corps, which proudly professes to leave no man behind, would own up to its mistakes. As they pushed the Marines to reveal what they knew about Lejeune's drinking water, and when, they figured that the motto Semper Fidelis ("Always Faithful") was more than just a sales pitch.

Now, they know better.

Kevin Shipp knows better, too. As an agent of the Central Intelligence Agency, he was stationed at Camp Stanley, an Army site right near San Antonio's heavily polluted Kelly Air Force Base. (During our conversation, Shipp would not reveal exactly where he was stationed or his job there, though other outlets had previously identified both.) Shipp and his family lived at the base, which is believed to be a secret weapons storage facility, for two years starting in June 1999.

Unlike the largely unsuspecting residents of Camp Lejeune, the Shipps realized quickly that something was amiss. One of his sons told The New York Times that "the house that our family was moved into was planted on top of a lot of buried ammunition. One time, me and my little brother dug up a mustard gas shell." Their house was also teeming with mold, which made them ill. "My children were bleeding from their noses, vomiting, had severe headaches and strange rashes on the exposed areas of their skin," Shipp later wrote. "My wife became bedridden with headaches so severe, she had to be placed on morphine. … I began to have burning in my lungs…and was losing my short-term memory."

In 2002, Shipp left the CIA and sued his employer for placing him in a mold-ridden house. The case was eventually dismissed on the basis of the State Secrets Privilege.

When we spoke, Shipp, who now lives in Jacksonville, Florida, described Camp Stanley as a "toxic mess." Not only is it littered with aging munitions, but its water has been poisoned in a fashion strikingly similar to Camp Lejeune's.

"Frankly," Shipp told me, "they don't care."

Men With Mastectomy Scars

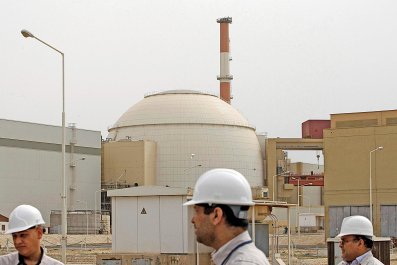

Camp Lejeune, built in 1941, is 240 square miles in area, making it the largest Marine base east of the Mississippi River, and the second largest in the nation after Camp Pendleton, near San Diego. Situated at the swampy mouth of the New River, it is an ideal training ground for the sorts of amphibious assaults that are the Marines' favored means of arriving at the war dance. From here, leathernecks shipped out to the Pacific theater of World War II, Korea and Vietnam. The Marines killed in the 1983 terrorist bombings of a barracks in Beirut had also come from Lejeune; a memorial to them sits in a wooded glade at the camp's edge.

In the decade before Camp Lejeune was built, the chemical industry saw the advent of the "safety solvents" TCE and tetrachloroethylene (PCE). These were chemical cleaning agents of the organochlorine group: TCE was a degreaser for machine parts; PCE was used in dry cleaning.

A military base is rife with machines. This sounds obvious, but it's quite striking when you see all those tanks and airplanes and amphibious vehicles that seem perfectly poised for battle, even on a humid North Carolina afternoon when overseas wars might as well be waged in another galaxy. Part of that readiness is cleanliness, which your average military mechanic would have achieved, until very recently, by washing grease-covered parts in TCE.

In 2004, a former Marine named Joseph Paliotti decided to clear his conscience. He was on the verge of perishing from cancer, and he suspected that Camp Lejeune had something to do with it. He had spent 16 years working on the base. "We'd come down there, we used to dump it: DDT, cleaning fluid, batteries, transformers, vehicles," he told his local television station. "I knew sooner or later something was gonna happen." Several days later, Paliotti died.

The cleaning of clothes might seem like a more innocuous matter, but that's only because most people don't have much of a notion of how a dry cleaning enterprise works. You surrender your clothes; they return immaculate. Magic! As it happens, the chemicals that cleanse a shirt are about as carcinogenic as those that cleanse an airplane engine.

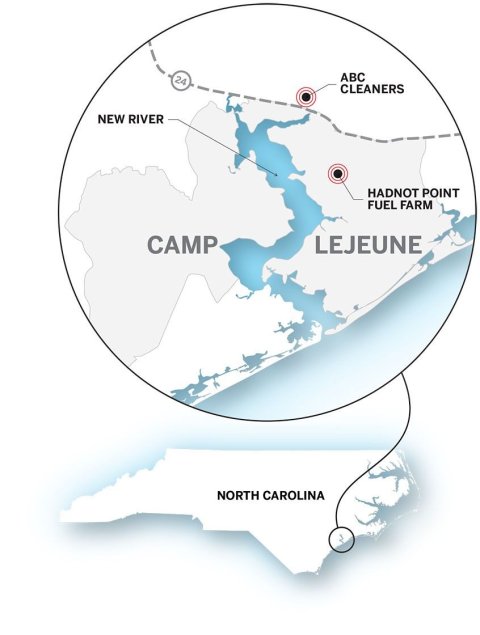

One of the places at Camp Lejeune that could care for your uniform was ABC One Hour Cleaners, which sits just a few yards from the edge of the base. The dry cleaners, which started operation in 1964 and ended on-site cleaning service in 2005, did nothing different from what thousands of other dry cleaners did around the United States: It used PCE as a cleaning solvent. Some of the PCE sludge was used to fill potholes, while much of the liquid waste ended up in the ground, just like the TCE used to clean machines across the road, behind the barbed wire.

The TCE and PCE percolated through the sandy soil of Camp Lejeune and into the shallow Castle Hayne aquifer, from which the base drew its water. Also flowing into the soil was benzene from the Hadnot Point fuel farm. A component of gasoline, benzene is an aromatic hydrocarbon. Its name does not mean that it is pleasantly pungent. Instead, the deceptively alluring adjective refers to the strong carbon-hydrogen latticework of the compound. Like other aromatic hydrocarbons, benzene is a carcinogen that readily enters the body.

An Associated Press report found that as "late as spring 1988, the underground tanks at Hadnot Point were leaking about 1,500 gallons of fuel a month—a total of more than 1.1 million gallons, by some estimates." Eventually, the leaked fuel would form an underground layer 15 feet deep, a carcinogenic band essentially covering the aquifer from which the drinking water was drawn.

Among those who drank that water was Mike Partain, who was born on base. His father was a Marine, as was his grandfather. He lived in the same housing complex where the Ensmingers conceived their daughter Janey. He joined the Navy but was discharged because of a debilitating rash that would overtake his body without explanation. Eventually, Partain ended up in Tallahassee, Florida, where he was a teacher and, later, an insurance adjuster.

Then married with four children, Partain was in good health until the age of 39. (He has since divorced; "my marriage didn't survive Lejeune," he told me.) Toxins, like terrorist sleeper cells, are patient. As he would later write for the website of Semper Fi, a documentary about Camp Lejeune, in April 2007 "my wife gave me a hug before bed one night. As she did, her hand came across a curious bump situated above my right nipple. There was no pain, but it felt very odd." Partain went for tests, which revealed an almost incredible diagnosis: breast cancer.

Male breast cancer is rare enough in the general population, especially for someone like Partain who has no history of the disease in his family. According to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, only about 7 breast cancer victims out of 1,000 are men. Yet it turned out that many other men who'd lived on Camp Lejeune had developed breast cancer: Partain told me that he knows of 85 victims. Several of these aging men, showing mastectomy scars, posed for a 2011 calendar.

Coincidences do happen, even in cancer epidemiology. What looks like obvious causation to some may be just cruel fate, but the overall infrequency of the disease, combined with its relatively high frequency among the men of Camp Lejeune, as well as the other ailments plaguing those who lived on the base, made clear that there was a connection. "This has all the characteristics of a male breast cancer cluster," the noted epidemiologist Richard Clapp said at the time. Camp Lejeune is, in fact, now widely believed to be the largest known cluster of the male variant of the disease.

"So Much Audacity"

The Superfund law, passed in 1980, did not apply to federal facilities until 1986. Once it was exposed to litigation, the Department of Defense could no longer dismiss the environmental movement as a mere leftist nuisance. The EPA did better under self-described "environmental president" George H.W. Bush than it had under Ronald Reagan. The Clinton presidency appeared to embolden the regulators, even as the centrist Democrat allowed the Superfund tax on industry to expire in 1995. The presidency of George W. Bush, however, proved a long-sought reprieve for polluters, as the wannabe Texan quickly stocked the EPA with friends of industry.

The attacks of 9/11 proved an especially ripe opportunity for the Pentagon to push back against the oversight implemented in 1986. With the EPA already weakened by the White House and the wounded country in a bellicose mood, the Pentagon asked, in 2003, for a pass on pollution. The Department of Defense figured that Americans were far more afraid of terrorists than polluters. "The manner in which certain environmental laws are being applied is seriously hampering our military training opportunities," Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld wrote in an April 2003 letter to EPA head Christine Todd Whitman.

Military officials did not anticipate the resistance they would encounter on Capitol Hill. Perhaps the most vociferous critic of the exemptions was Dingell. "Nowhere has a single set of legislative proposals had so much audacity and so little merit," thundered the aging legislator during one hearing. "I would note that the Defense Department is supposed to defend the nation, not to defile it."

Despite an industry-friendly White House on its side, the Pentagon failed to earn the exemptions from environmental laws. Just as important, its overreach brought national attention to the then little-known problem of military pollution, with Camp Lejeune coming to serve as an example of what happened when the Department of Defense was left to police itself.

Sullivan, the Pentagon's chief environmental officer, said that to clean up all of the Pentagon's pollution would cost American taxpayers $27 billion. Nevertheless, she is upbeat about the challenges before her, noting that the Department of Defense has done all it could to meet new regulations. Its shortcomings, she said, resulted from a widespread ignorance about the danger of certain chemicals, which was hardly restricted to the Pentagon. "We all grew," she told me, "at the same time."

Others are skeptical of the Pentagon's efforts to come clean. One report by the religiously nonpartisan U.S. Government Accountability Office deemed "daunting" the Pentagon's "task of cleaning up thousands of military bases and other installations across the country." It concluded that "identifying and investigating these hazards will take decades, and cleanup will cost many billions of dollars." The GAO has also found that regulators lack the muscle to make the Pentagon clean up its many messes.

"A World Trade Center in Slow Motion"

Today, Camp Lejeune is a tidy base of red-brick buildings and thick groves of pine. Occasionally, one sees vistas of the New River, which opens into a bright blue bowl of a bay. Marines can rent cabins on a beach that recalls untrammeled stretches of Cape Cod. The base is home to a rare variety of woodpecker, as well as the Venus flytrap. The place looks ordinary, even pretty in places, if you can get past the punishing Southern heat. It is like a body whose wounds have healed, though the scars are still visible if you know where to look: the yellow poles of observation wells, empty lots behind barbed wire, groves in which dump sites hide. But most people aren't looking.

We pass an unexceptional building on the side of the road. Here, the base once stored the toxic pesticide DDT, made infamous by Rachel Carson's Silent Spring. Later, the same building became a day care center, with kids playing in ground soaked with an incontrovertible poison. I told the environmental officials who led me around the base that I was reminded of something that Ernest Hemingway once wrote: "All things truly wicked start from an innocence." I don't think they knew if this was supposed to be condemnation or exculpation. I don't know, either.

The ignorance argument falls loud and flat when it comes to TCE, which could have been classified as a known carcinogen much earlier than 2011, which was when the EPA finally released its long-awaited determination of the solvent's manifold dangers. According to a two-part Los Angeles Times series on trichloroethylene, the EPA realized in the 1990s that TCE was "as much as 40 times more likely to cause cancer than [the agency] had previously believed." Its efforts to classify TCE as a carcinogen were largely hindered by the Pentagon, which produced experts confidently assuring that TCE's danger was overblown. Those attempts at assuaging concerns failed, but the delay was costly, while the contamination remains vast and the cleanup has been slow. David Ozonoff, an epidemiologist at Boston University, called the nation's TCE problem "a World Trade Center in slow motion."

The public affairs and environmental officials who took me around Camp Lejeune were young, informed and sunny in disposition, not quite the clenched-anus Dick Cheney minions one expects of the nefarious military-industrial complex. They told me, proudly, that the water at the base was now probably the cleanest in the nation. One hears a similar refrain about both Woburn, Massachusetts, and Toms River, New Jersey, the infamous cancer clusters where water was also tainted with TCE. What they don't say is that today's pristine water has been paid for by past generations, many times over.

Yet several dozen sites remain, each benzene plume, munitions dump and TCE-laden lot its own private battlefield. It will be decades before the base is fully clean, though past neglect appears to have been replaced by penitent diligence. Solar thermal panels have already been installed on 2,000 homes, improbably making Camp Lejeune one of the largest residential communities in the nation to use solar energy. Even more improbable, earlier this year Camp Lejeune won an environmental restoration award from the Pentagon, beating out bases across the various services. Of course, that's partly because there was so much here to restore.

"They're Slick"

In 2012, advocates like Jerry Ensminger and Mike Partain won a victory when President Barack Obama signed the Honoring America's Veterans and Caring for Camp Lejeune Families Act, which is supposed to ensure that those sickened by Lejeune water get medical treatment from the Department of Veteran Affairs. The law is also known as the Janey Ensminger Act, a nod to the father who turned his howling grief into righteous anger. In the Oval Office, Ensminger stood next to the president and looked over his shoulder, as if to make sure the bill was properly signed.

Ensminger said working on Camp Lejeune has been like "pulling teeth." He wasn't exaggerating all that much. Earlier this spring, Obama's Department of Justice filed an amicus curiae brief to the Supreme Court in CTS Corporation v. Waldburger, in which 25 Asheville, North Carolina, residents were suing an electronic firm for contaminating their well water. The brief was in favor the polluter, not the alleged victims. That seemed to put the administration at odds with its position on the treatment of victims of toxic exposure.

When the Supreme Court ruled in favor of CTS in June, it essentially said that North Carolina's 10-year statute of repose trumps the Superfund law's statute of limitations. A statute of repose is much friendlier to business, while a statute of limitations favors those, like Ensminger, who might want to sue a potential polluter, since it gives them much more time to discover the result of their illness (which could take far more than a single decade to manifest). Some observers noted that the Supreme Court ruling could make it difficult for the Camp Lejeune lawsuits to proceed.

"It doesn't matter," Ensminger said a couple of days before the Supreme Court decision. "I'm not quitting." In the hours after the ruling, he and his lawyers quickly identified a seeming loophole in the majority opinion that they were eager to exploit, while North Carolina legislators rushed to pass legislation that would preserve the legal claims of both CTS and Camp Lejeune victims. (North Carolina Governor Pat McCrory signed the bill in late June.)

"You gotta watch these people like a hawk, man," Ensminger told me of the Marines. "They're slick." The armed forces took his daughter. They took so many other lives, too, without firing a single shot.