There are few more cautionary tales in rock than Randy Newman's "He's Dead (But He Don't Know It)," the lament of a worn-out star ("I've nothing left to say / But I'm going to say it anyway"). On Sunset Boulevard, eternal home of that mythic denier Norma Desmond, you can still pass billboards touting product by singers long past their prime. It is there, in the penthouse offices of Annie Lennox's manager, that I tell her that I cringed when I heard she was doing an album of American standards (Nostalgia, Blue Note Records). Made me think of Rod Stewart, I said.

"You're absolutely right," she said. "And he's done incredibly well in terms of his sales. But knowing that that could be the graveyard for people of my generation, it was very clear to me that I must put a lot of myself into these songs."

I thought of the graveyard line when her label hosted a lavish listening party a few weeks later at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery, which the rock journos in attendance (talk about a group in denial!) seemed to love almost as much for the free drinks as they did for being in the presence of the former Eurythmics singer. The music got a rapturous reception, and then Lennox answered questions from Rolling Stone's Anthony DeCurtis. Why the setting, he wondered? "Because these songs have outlived their composers," she said, joking that some of the writers of the songs on Nostalgia (Hoagy Carmichael, George Gershwin) might be buried there. (They're not.)

But why record at all? She's been absent from the scene for a few years, deeply involved in causes like mothers2mothers, an organization co-founded by her husband, Dr. Mitchell Besser, that works with HIV-positive pregnant women in South Africa. "I don't want to twerk," she said, "but I want to be relevant."

At 59, Lennox is luminous the day of our interview, dressed in jeans and a Mexican peasant blouse, no makeup, short silver hair instead of the orange crew cut she made famous in the 1983 "Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)" video. She talks about her passions du jour, including Israel's bombing of Gaza (in full swing when we met) and the reaction she got when she joined an anti-Israel protest in London during the last Hamas conflict, in January 2009. "I was accused of being anti-Semitic," she recalled. "Can you imagine what that feels like for me? My children are half-Jewish, my husband is Jewish." Her security told her to stay out of such demonstrations, so now she mostly posts on her Facebook page. "Half the population of Gaza is young people under the age of 15. What are they supposed to do? What do we think of them? Do they have a right to live?"

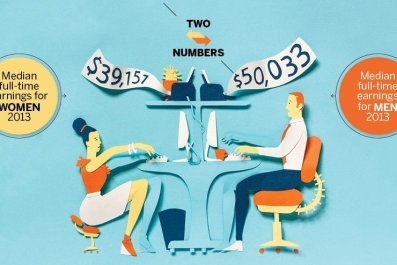

Lennox has been a tireless ambassador for many causes (Oxfam, Greenpeace, Doctors Without Borders), but as she ages and travels, the thread connecting her interests has emerged. "What has become more clear to me is that the root cause of many of these things is women's rights," she said. "I feel that the way forward for feminism is in the developing world as well as in the West."

She did not always identify herself as a feminist (this from the woman who performed "Sisters Are Doin' It for Themselves" with Aretha Franklin in 1985). "I started to realize as a woman that my gender was something I had kind of taken for granted," she said. "I've always been totally self-reliant, and while I believed in feminism, I wasn't at the front lines."

On Nostalgia, Lennox tries to bring a woman's perspective to many of the songs. Her cover of Screamin' Jay Hawkins's "I Put a Spell on You" (more blues than jazz) is in the witchy woman tradition of Nina Simone's version, though not totally derivative. As with many of the songs, it sounds like Lennox just heard them—in some cases (like "I Cover the Waterfront") because she had. She claims the inspiration for the album came to her when performing Cole Porter's "Ev'ry Time We Say Goodbye" (which she covered to great effect on the 1990 Red Hot + Blue album) with Herbie Hancock and his band at a U.N. AIDS concert in 2012. "I was rehearsing with his musicians, having some fun," she said, "just extemporizing, and I suddenly thought, Hmm, I can do this."

The list of pop singers who said to themselves, when performing with Herbie Hancock, "I can do this" is probably short—though Joni Mitchell, one of Lennox's idols, is among them. It was Mitchell whom she looked to for inspiration when she was first writing songs in the early 1970s. She had gone to the Royal Academy of Music in London at 17 but dropped out before taking her final exams. "My parents were shocked," she says. "They said, 'What are you going to do?' They thought maybe I'd be a teacher. At a certain point, things came together for me, and I thought, I want to write songs. And I want to sing the songs I've written…and Joni Mitchell was the prototype for that."

Her lucky break came, she says, when she met Dave Stewart. Even in the London scene of the mid-1970s, Stewart stood out: He wore fur coats and space helmets, he'd done a lot of drugs, been in bands and been married. "I felt I met my counterpart," said Lennox. "We kind of shaped each other. We kind of rescued each other a bit, I think." The two were romantically involved but had become more musical partners by the peak of the Eurythmics's fame; they produced dozens of international hits, gave women a strong (if somewhat androgynous) heroine in Lennox's public persona and sold more than 75 million albums worldwide. When I ask her if she is still in touch with her erstwhile cohort, she is reticent for the first time in our interview.

"Mmm…" she muses, and then: "Ish. Less so.… I feel like a lot of our thing is the past.… My life now, if I compare it to what it was decades ago, I'm the same person, but I'm so not that person.… Like all of us. You're not 7 years old, you're not 27 years old. But you also think, Who am I, then? When was I ever me?"

The angst that fueled her songwriting in the past is gone, she says. "I was very unhappy, for many, many years. And I think unhappiness is a great muse for artists." She can identify with Duke Ellington's "Mood Indigo," the album's closer: "It's about depression, as low as you can get," she says. "I've been there, I know what that is." But generally speaking she'd rather someone else be depressed, and just sing about it.

There's a nod to the Boswell Sisters in her cover (she discovered their close harmonies searching 1930s songs on YouTube), and it goes out like a New Orleans funeral march. Those bands always begin with a dirge, but they're happy when they're leaving the graveyard—and think you should be too—because they're the ones still dancing.