In the cosmic equivalent of a hole-in-one, the Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro) last week guided Mangalyaan, a 1365kg space vessel 680 million kilometres away from Earth and successfully placed it in orbit around Mars.

In the global history of missions to Mars only 21 out of 51 have succeeded, and India is the only country to have made it on its first attempt (between 1999 and 2012, both China and Japan launched failed attempts to send spacecrafts to Mars). Apart from the bragging rights of being among only one of four space agencies (and the only Asian one) to get so near to Mars, the exercise cost a mere $73m – less than "the cost of the Hollywood movie Gravity," as the Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, quipped.

The successful launch was a much-needed PR success for a country that, since the advent of a new government in May, is trying to market itself as the go-to destination for industrial investment. Notwithstanding the mission's six-month quest to spot and speculate on the mysterious methane in Mars, a panoply of Indian companies from space parvenus to veteran manufacturing companies – already seem to have sniffed an opportunity to mould India into the next hub for space industry-led outsourcing, after software, accounts and BPOs.

Susmita Mohanty, CEO of Earth2Orbit, a budding private space company in India, is unequivocal that India stands on the cusp of an enormous opportunity that it simply cannot afford to waste. "Mars Orbital Mission's (MOM) success is huge, not just for India but for all mankind," says Mohanty. "In my lifetime, I want to see space travel become affordable – similar to what happened with commercial aviation in the last century."

The opportunity that she alludes to is the current state of the global space industry. In the United States, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa) has over the past two decades reformulated its approach to space travel. It will concentrate only on developing (and not launching) space capsules to ferry humans to the nearby asteroids, the moon and eventually Mars and has outsourced to private companies the task of building space launchers and organising crew and cargo trips to the International Space Station (ISS).

India is poised to take advantage of the changes in focus for a number of reasons. Critical to Isro's success on the Mars mission was a redoubtable launch vehicle, called the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle, which was built from scratch and relentlessly tweaked over three decades (partly because of hobbling technology embargoes following India's nuclear tests in 1974). It has now become a carrier of choice, even internationally, for carrying light satellites (less than 1,500kg) for a range of telecommunication and scientific space missions.

To reduce its costs and save time, Isro doesn't make multiple prototypes or conduct numerous field tests, but instead relies on software simulation – unsurprisingly, given India's traditional strength in information technology and software services – to anticipate what could go wrong and test the parameters of its vehicles.

"The Russians rely much more on ground tests and the Americans slightly less so. We have our own philosophy," says K S Radhakrishnan, chairman of Isro. "Flight tests are expensive and moreover there is no consistent success-failure pattern vis-a-vis an agency's testing philosophy."

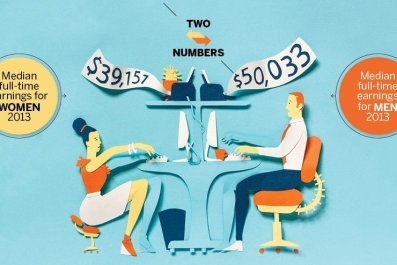

Mangalyaan was economical because Indian scientists get paid roughly a fifth of the salaries of their counterparts in space agencies in Europe and the United States. Low costs are reflected in the entire ecosystem of manufacturers that include nearly 400 Indian private companies making different parts of the rockets and satellites. The industry has also relied on sustained support from the government since the 1960s when India, under its first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, consciously embarked on a policy to support expensive high science such as nuclear and space programmes over primary education and low-tech manufacturing.

"That was the strategy which was adopted in those times for better or worse, but undeniably the Mars mission's success is a result of all those decades of planning. Now there is chance to reap the fruit of those investments," says Rajeswari Gopalan, a space and security studies expert with the Observer Research Foundation, a New Delhi-based think tank.

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, an American non-profit organisation, nearly 50 countries have their own satellites. Other than for military purposes, they are used to manage burgeoning mobile-phone subscriber bases and satellite television networks. On the other hand, only nine countries and a consortium of European nations are capable of launching these satellites. Given this imbalance of supply and demand, even new entrants can undercut established players and take over markets rapidly.

For instance, the 2014 report of the US Satellite Industry Association and moonandback.com, a US website that tracks activity in the space sector, suggests that the US has lost its pre-eminence as the satellite launcher of the world after Nasa retired its shuttle programme in 2011.

Ariannnespace, the French agency that used to launch all satellites developed in Europe, has launched 50–60% of the commercial satellites in the world after 2011. On the other hand, when accounting for the total number of space vehicle launch events, which includes satellites as well as launches to the ISS, space tourism, and missions that are conducted both under government and commercial contracts, Russia has now emerged as the world leader in space launches.

"They are significant competitors, but India has certain advantages that it can reliably and strategically use to build a case for greater market presence," says S M Vaidya, executive vice president of Godrej & Boyce, a 117-year-old company that made portions of the multi-stage engines used to propel the MOM. "For one, we enjoy more cordial relations with several countries across Asia and the world and have more transparent policies. Secondly, India is blessed with having launching facilities that are close to the equator and therefore significantly cuts fuel costs for launches," says Vaidya.

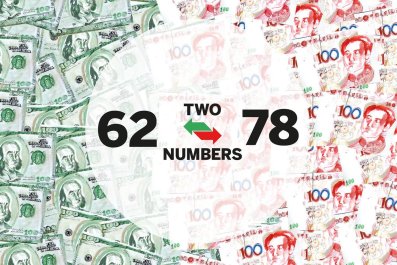

India can offer "a low cost, single-window package that can be used to substantially offer lower costs than its competitors," says Ajey Lele, a New Delhi-based expert on space and defence strategy and author of Mission Mars: India's Quest for the Red Planet. Though Isro doesn't disclose the cost of its launches, Lele – in an article for Space Review – estimates that Isro has offered launches at 75% of the prices charged by other agencies.

Nearly all of Isro's space missions are currently for launching Indian satellites, and the agency carries international satellites only if there is space left over on its launch vehicles. Since 2012 it has begun to launch space missions that are predominantly for commercial space missions and this June, for the first time since the advent of India's space programmes, Isro directed a completely commercial mission where all satellites on board were foreign – from France, Germany, Canada and Singapore. "Apart from the Mars mission, that's another reason why this is a significant year because we have shown that we can significantly contribute to important science as well as be a destination for commercial missions," says Vaidya.

However, "for India to participate and be competitive in the $300bn-plus global space economy, India must adopt an extroverted space policy, promote related exports and empower Indian companies to reach beyond serving domestic needs to compete internationally. We also need to get rid of our "IT (information technology) blinders" and see "space" as the next big frontier," adds Mohanty.

Before that, India needs to convince the world that it can launch heavy satellites. The successful PSLV cannot carry satellites and other payloads greater than 1600kg, whereas the communication satellites launched by the Russian, Chinese and European agencies weigh 2-6 tonnes. According to industry reports, more than 80% of the revenues from satellite launches come from heavy satellites and though India has spent more than two decades developing a class of rockets called the Geostationary Satellite Launch Vehicles (GSLV) it still can't reliably depend on them. To realise a reliable GSLV, India must develop a stable cryogenic engine and since 2001, when India launched a GSLV for the first time, it has had an abysmal 26% success rate.

In January this year, Isro successfully launched a heavy communications satellite on the GSLV after four consecutive failures. "This was still a developmental flight and once it goes through a couple of flights more and can reliably convince customers, it would mark India's entry into the big league," says Lele.

Private industries in the US, Russia and Europe rely on a mix of defence, aerospace, aviation and space-related manufacturing. India, being the world's largest arms importer and woefully lacking a viable defence and aerospace industry, needs to market its space product and provide more incentives for manufacturers to make Isro's efforts generate more revenue. Isro's plans over the next 10 years include landing a vehicle on the moon aboard the GSLV by 2016, sending Indian astronauts outside the confines of Earth's orbit and, at the same time, maintaining the organisation's national mandate to remain relevant to the needs of India where poverty is still rampant.

"That's been the core of Isro's mandate. We have to continue providing education to India's remotest villages, tell fisherman using satellite imagery where they can find the best catch and help our weather agencies predict cyclones and droughts," says Radhakrishnan, "and at the same time, not lose sight of the stars."