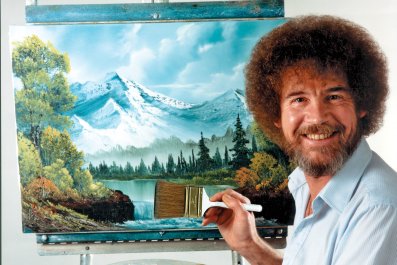

Watching Timothy Spall as the artist William Turner stabbing the canvas with his brush or spitting on to the paint to loosen it, is to witness the physical investment of two artists. This is not just the portrait of an artist but of a compulsive, obsessive painter "investing" the work with his very essence. This is painting as a holistic expression, a fusion of the intellectual and the visceral complete with false starts, frustrations and last-minute additions. But it is also a testament to an actor's extraordinary commitment to his role.

Mike Leigh's Mr Turner, opens next month, having already won the Best Actor prize for Spall at the Cannes Film Festival as well as the best reviews of his distinguished career. The two and a half years he devoted to learning to paint like Turner have evidently paid off.

"One thing you can't do is turn up on set without doing your homework," says Spall. "But there is no doubt that acting has become more sophisticated. We are leaning towards expectations of verisimilitude."

Spall is not alone among actors who are prepared to invest huge amounts of time and energy into submerging themselves in a role for the sake of "verisimilitude". Daniel Day-Lewis is the most obvious example, though he is by no means the only one. We are in an age of heightened observation and demand a greater commitment from actors who are required to go a great deal further in creating believable characters. Faking it is so last year.

Leaving Leigh's singular filmmaking processes aside, the shift from pure technique to total immersion has been accelerating ever more rapidly.

The question is: what is driving this extreme commitment? Actors, directors or the audience? Clearly, directors like actors to be prepared for their roles as it means they don't have to waste time discussing "motive" on set. And the search is always on for actors who are "right" for the role from top to toe. But it is also a mark of the sea-change in the business of acting. Modern audiences seem to require perfect replications of reality, paintings that look like photographs. The gulf between old-school technique and post-method immersion is growing ever wider.

When method actor Dustin Hoffman stayed awake for three nights to replicate exhaustion during the filming of Marathon Man, his co-star Laurence Olivier – a theatrical knight of the old school – remarked, "Try acting, dear boy. It's much easier."

There was a time when actors created characters from the ground up. More than one actor has claimed to start with the shoes. This approach is a legacy from the days of repertory theatre, when actors would be cast in a variety of roles and prided themselves on their ability to switch from old men to juvenile leads and from Agatha Christie to William Congreve in less than a week.

"In the old days you went straight from drama school to rep," says Spall. "You had to come up with characters very quickly, often playing people you might not be right for. It was a fast track to versatility. But it was also a fast track to being a ham."

The rise of psychoanalysis and the need for a "subtext" has pushed the research levels deeper. When Stanislavski wrote An Actor Prepares while working with Chekhov at the Moscow Art Theatre in the 1900s, he can hardly have imagined the long-term impact his book would have on the profession.

Stanislavksy's "method" – which requires an actor to locate emotional and psychological elements within himself that accorded with those of the character he is playing and "use" them in the role – was taken up by Americans like Lee Strasberg and subsequently Stella Adler and Sanford Meisner to create what is now known as The Method School. Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando, Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Dustin Hoffman all adhere to the method, even if they torqued Stanislavski's teachings into their own systems.

Instead of working from the outside and drilling into themselves to locate a character, actors begin from the inside and work their way out. But it is a process that has psychological as well as physical consequences. There are inherent dangers in this approach if taken too far, resulting in potential distortion of the persona and – in extreme cases – schizophrenia and total detachment from reality.

Daniel Day-Lewis has admitted that his intensive and lengthy preparations for roles has often made him impossible to live with. As Hawkeye in The Last of the Mohicans, he ate only food that he had himself killed – having first learnt to hunt, trap and skin wild animals. As the paraplegic writer Christy Brown in My Left Foot, he insisted on being carried everywhere and spoon-fed between takes to maintain the essence of his role. A temporary separation from his own personality necessitates a temporary isolation from his normal life, including his family. Christian Bale's extreme dieting and exercise regimes for his various roles – losing 28kg to play the skeletal figure of The Machinist by existing on nothing but coffee, water and an apple a day for four months – is pushing his body to limits of human endurance. When Robert De Niro gained weight for the ageing, overweight Jake LaMotta in the later stages of Raging Bull, filming had to stop when he began to experience breathing difficulties.

The immersive style brings its rewards, as many have found. Day-Lewis has won three Oscars. And there are peripheral benefits to immersive research. Aside from painting, Spall has learnt to play the piano, drive a minicab like a professional and, as a result of intense homework for the role of Albert Pierrepoint, Britain's last hangman, he claims he could perform an execution with confidence. "Yes," he says. "I could have hanged somebody after that. I wouldn't want to. But I could have."

This expectation of reality has arisen as a result of television and film, says John Bashford, Vice Principal and Head of Acting at London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art. "It is the lens, without a doubt. Our training delivers a good grounding in truth but we don't have time for fully immersive techniques."

But the requirement for authenticity is in danger of going too far. Matthew McConaughey lost 23kg for his role as an Aids victim in Dallas Buyers Club by "chewing a lot of ice". Robert De Niro spent $5,000 having his teeth ground down and deformed by a dentist for his role as psychopath Max Cady in Cape Fear.

Bashford has doubts about some of these extreme physical makeovers. "It is an area that is fraught with danger. Hollywood is obsessed with body image and each artist has his own way of forging character. I'd probably go slightly potty if I had to engage in those extremes."

The inherent dangers of personality fragmentation and anxieties are the stock in trade of Dr Desmond Biddulph, a psychiatrist who specialises in conditions presented by those engaged in the performing arts.

"A lot of actors only feel real when they are taking a part," he says. "They don't feel confident as themselves. Whenever they are engaged in a role their anxieties disappear."

There is worse to come. He refers to a condition called "conversion hysteria" in which actors can bring about physical alteration – positive and negative – as a result of their roles. He cites an actress in soap opera EastEnders whose character is suffering from breast cancer and who has lately confessed to feeling "quite ill" as a result.

Although he believes that acting is a normal human function that allows us to accommodate and adjust to various situations, there are specific dangers for actors. "The problem occurs when actors go too far and create a total self-abnegation of their own persona to forge a character. It's no longer acting."

Moreover, the increasing search for the "real" takes something away from the audience, he believes. "You lose the participation aspect between actor and audience as you no longer have to exercise your imagination. It's all a bit too real."

Clearly, the forensic nature of film and television necessitates a more rigorous approach to naturalistic detail, a finer thread in the weave of character. Timothy Spall believes that the vogue for reality television, docudramas and soap operas has led to an increased intimacy between viewer and performer. "It is easier to see the technique now," he says. "And it looks wooden."

But, he adds, there are also dangers in pursuing veracity through naturalism. "A lot of actors think that doing nothing is naturalistic when all they are doing is . . . nothing."

The current obsession with character saturation is accompanied by the danger of psychological fragmentation. At its best, actors evolve into living caricatures of their most famous roles, like Edward Fox or Robert Hardy. At its worst it can result in severe psychological trauma which – in the cases of Philip Seymour Hoffman and Heath Ledger – can have fatal results.

Much depends on the role and the nature of the absorption. After two and a half years of practice, Spall is now a more proficient painter than he was; Daniel Day-Lewis famously had a nervous breakdown when he "saw" the ghost of his own father while playing Hamlet. It is, as Spall remarks, "horses for courses".

"Humankind cannot bear very much reality" wrote T S Eliot. Maybe Olivier had a point. It is time to return to "acting". It is not necessarily easier but it is, undoubtedly, less dangerous.