Between the 75th anniversary of the start of the Second World War and the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, we examine Germany's profound lessons for the developed world in the second of our Newsweek Essays. The author, Stephen Green, was chairman of the world's second largest bank, HSBC, and served as the UK's minister for trade and investment until 2013.

What do you call the country that sits at the heart of Europe, which is its biggest and strongest economy, and which increasingly calls the tune in the European Union? Not its leader. You can't translate that word into German without making Germans wince – it still conjures up the nightmare of the Führer. Not the hegemon of Europe – a word sometimes hurled at Germany by Mediterranean politicians, who rail against what they see as its puritanical demands for eurozone austerity. Hegemony – the indirect rule exercised by one city-state over another in Greek antiquity – hardly does justice to two key hallmarks of the modern Germany: its consensualism, and its deep commitment to its own integration within the "ever-closer union" envisaged for the EU by its treaties.

A better image for the new Germany in the new Europe is that of a reluctant Meister.

Meister. The word conveys a sense of respect due to experienced excellence, which knows the secrets of success and leads by example. It has its roots in the world of commerce: the Meister has served one of those famous German apprenticeships and is the honoured master of the craft. But also in culture: it is the Meister who conjures up the music from the orchestra. Now Germany is also the Weltmeister – the world champion – of the world's favourite sport.

Yet its discomfort with leadership is as obvious as the reality of its dominance. Until recently, the contrast with British and French willingness to use hard power in foreign affairs was stark. Now, the difference is less striking – not because Germany has become readier to throw its weight around. It hasn't, as the crisis in the Ukraine shows. But Britain and France have grown less sure of themselves. Germany, meanwhile, has become the reluctant Meister of the new Europe.

This was certainly not foreseeable in May 1945.

It is easy now to forget just what a total catastrophe had occurred. The moral bankruptcy was complete. The devastation was so widespread that the challenge of creating a functioning society was mountainous. More than 150 cities lay largely in ruins; transport systems, power and water supplies were barely working; the currency was worthless; millions of people were displaced; and mass starvation was a real threat in the vicious winters that followed. It seemed all too obvious then that Stunde Null – zero hour, as it was called – was the end of all that had been. It was not at all obvious that it might be the beginning of something new.

Indeed, past experience pointed to something very different. Looking back, the Germans had learned to see themselves as victims. Victims of the dreadful Thirty Years War in the 17th century – by far the worst war in Europe until the 20th century. Victims too of French aggression under Louis XIV half a century later; and victims yet again of the French under Napoleon. All this might have been distant in time, but had been etched in folk memory. Victims, finally, of the vindictive settlement imposed on them in the Treaty of Versailles at the end of the First World War.

And now the experience of total defeat had provided reason enough for a resurgence of this victim psychology. There is probably no such thing as a morally clean war, and there were inevitably uncomfortable questions to be asked on all sides about the Second World War – even though it undoubtedly had to be fought against an undoubted evil.

First: the Allied bombing campaign. The use of this new tool of war as a means of spreading terror and causing social breakdown was, of course, begun by Nazi Germany (Guernica, Warsaw, Rotterdam, Coventry, London, Stalingrad). The Allies began to respond in kind with increasing might and ferocity – particularly from July 1943 (the first major attack, which created a firestorm in Hamburg). Neither the German nor the Allied use of bombing can be remotely interpreted simply as legitimate targeting of productive infrastructure. The attack on Dresden (February 1945) is infamous. The attacks on Pforzheim (February 1945 – which produced the highest casualty rate of all), Würzburg and Magdeburg (March 1945) or Halberstadt and Potsdam (April 1945) are just other and later examples of what would be considered war crimes if they were carried out today.

Then there was the behaviour of the Allies as they invaded German lands from late 1944 onwards. The rape of hundreds of thousands of women by the Red Army was an atavistic rampage that the authorities did little to control. French behaviour in the Black Forest town of Freudenstadt was hardly better. Both had been occupied by Germany, of course; both had built up deep reserves of hatred. But what kind of a vengeance was this? Again, there is no monopoly of guilt.

And thirdly: the displacements and deportations. The torpedoing of the "Wilhelm Gustloff" in January 1945, which cost the lives of several thousand refugees from Königsberg, was the worst maritime disaster ever. It has become iconic in the German mind. In the end, more than 16 million Germans were expelled from the east, under merciless conditions. At least two million died after the end of the war, as resentments and hatreds that had built up over the years came pouring out. These deaths lie at the door, not just of the Russians, but of Poles, Czechs and others. Once again, the evil perpetrated by Germans may explain, but cannot justify, the response. Once again, there is no monopoly of guilt.

So yes, there should have been plenty of reason to fear a renewed sense of victimhood – with all that this might mean for the future. All human history cried out that victimisation provokes retaliation and revenge. Hitler lived and breathed this principle: he envisaged that underground resistance fighters ("werewolves") would carry on the fight after the fall of Berlin, and that even if it took a few generations, Germany would get its own back, especially against the Slavs.

Yet something different and strange happened. Somehow, a law of human nature was abrogated. It is as if the extreme and unique collapse freed the country from a fundamental human reflex and enabled it to find an unpredicted renewal and redemption. The result: a new economics, a new politics, a new psychology. We have perhaps become too familiar with it; and though the Germans often seem to recognise it least of all, the fact is that by any standards, the modern Germany is an unpredicted and extraordinary story of transformation.

To begin with the economics: the start of Germany's post-war economic boom begins in the depths of the exceptionally cold winter of 1946-47. Food was being hoarded by farmers, cigarettes and chocolate were the only trusted medium of exchange, and a human disaster was in the making. The turning point that got the economic motor going at last was the launch of the Marshall Plan and the currency reform which introduced the Deutschmark. The former made huge funds available for reconstruction: the latter provided the basis for a sound monetary policy that would underpin a strong savings rate and long-term investment. The contrast with conditions after the First World War is stark: then, the new Weimar Republic had been saddled with war reparations, and its middle classes were bankrupted by hyperinflation. Now, the emerging west German polity – which in 1949 became the Federal Republic – was launched with an impetus which created the basis for the Wirtschaftswunder, or economic miracle, of the 1950s and 1960s.

Throughout its first decade the economy grew at an average of 8% – twice as fast any other major economy in Europe. This performance was sufficiently strong to enable the Federal Republic to successfully absorb the enormous influx of Germans expelled from the east – an increase almost overnight of over 20% in its total population.

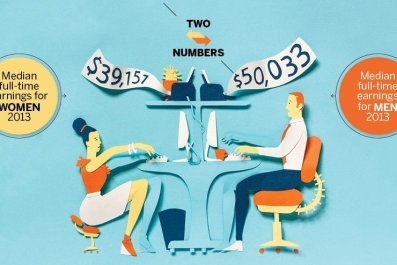

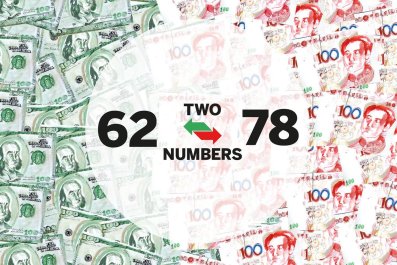

German expansion was powered first by reconstruction and then by exports, especially of manufactured goods. In fact, its performance was so strong that by the time of reunification, Germany had become the largest exporter in the world – a position that it did not lose until 2010: even now it is still the second largest after China and has much the strongest export market of any major developed economy.

Germany has become the European partner of choice of the developing world. 'Vorsprung durch Technik' – the advertising slogan of Audi – came to summarise the essence of what the country had to offer to emerging markets hungry for German capital goods and premium cars. Perhaps the clearest evidence of the standing of German industry on the world stage is the fact that the Chinese make no secret of treating Germany as their main strategic priority in Europe, to the point of holding regular joint top-level government meetings – something they have granted to no other developed country. By any measure the German economy has travelled a long way from the rubble of 1945.

But the new politics have been at least as important as the new economics. When the Federal Republic was established, there was nothing in past experience to indicate that it would succeed. The country had known nothing but the unspeakable Third Reich, the unstable and floundering Weimar Republic, the bastard democracy of Bismarck's Second Reich, and absolute rulers before that.

Yet, in the following decades, the Federal Republic went on to demonstrate its robustness beyond any question. It produced a succession of stable governments from the first moment when Konrad Adenauer was elected Chancellor by a majority of one vote (famously, he voted for himself). Adenauer dominated the political life of the Republic until 1963, and for several years after that the Christian Democratic Union benefited from the halo effect, even though its position was weakening. So when the close 1969 election resulted in a coalition of the Social Democratic party and the liberal Free Democrats – with the SPD leader Willy Brandt taking the chancellorship for the first time – this was a watershed. If one of the hallmarks of a healthy democracy is the ability for power to change hands constitutionally and peacefully, then this was the time when the Federal Republic passed that test.

Overall, the colour of government has changed since then along a spectrum between right of centre and left of centre in response to shifts in the electoral sands, in a way which is almost a classic sign of mature democracy. Change has taken place at a frequency high enough to be evidence of responsiveness to underlying popular demand, and yet low enough to allow for stability. Since 1949, Germany (first West Germany and then the unified country) has had eight chancellors; over the same period, the United States has had 12 presidents and the United Kingdom has had 14 prime ministers – and Italy has had more than 60 governments.

Meanwhile, over the decades of Germany's rise to prosperity as a mature democracy, there has been a parallel journey of integration by this new Germany into a new Europe. In the first two decades, Adenauer's West Germany anchored itself in a Western Europe which was itself a US sphere of influence. Then, under Willy Brandt from 1969 onwards, this Germany moved to recognise the other Germany – the German Democratic Republic – and to build a relationship with the Soviet sphere which accepted realities in Eastern Europe. Twenty years later, on Helmut Kohl's watch, came the unexpected and historic window of opportunity; the Federal Republic absorbed the failing GDR, following which the next two decades saw the admission to an expanding European Union of the rest of the former Soviet empire in Europe. And now there is a fourth phase – which is still unfinished business – whose dominating German figure (and European leader) is Angela Merkel: the consolidation of the eurozone as the core of the European Union.

So this is a story not just of an economic Weltmeister but of a political transformation that has been every bit as dramatic.

But there is still more.

Because out of the abyss came not just economic prowess, not just a robust new democracy, but a new psychology.

One sign of the psychology is revealed in the commemoration of Germany's war dead. On a memorial to the dead of the First World War in Berlin is a list of those who had fallen "in the struggle against a world of enemies". After the Second World War, such a sentiment was inconceivable. The mood since then is better captured by the memorial to four brothers killed on the Russian front: "their sacrifice is our warning." And there is no clearer indication of the traumatised rejection of nationalist aggression than the gulf between the social standing of the old Wehrmacht and of today's Bundeswehr.

Read our first Newsweek Essay, Emile Simpson's examination of the way smart phones have drastically altered the dynamics of modern warfare

This is perhaps the most remarkable fact of all about the new Germany. Not that this change was easy. Nor that it happened overnight. It required painful and drawn-out confrontation with the sins of the past. Terrible things had been done. Even now, seven decades later, the sheer scale and methodical thoroughness of the genocide can take our breath away. At Treblinka, there was no overnight accommodation for its victims: the trains arrived in the morning, and their passengers were dead by lunchtime.

Facing the facts was not, however, simply a matter of tracking down those directly guilty of crimes against humanity. It was also a wider confrontation. Whatever the limitations of the trials in West Germany in bringing perpetrators to justice, they certainly established a firm foundation of facts. They thus begged an obvious question for all those who had been adult, responsible citizens of the Third Reich. What had they done or not done? As a stone thrown into a lake sends ripples outwards, so – particularly from the late 1960s onwards – the question began to be asked more and more insistently.

The decline of subservience among those who were born from the 1940s onwards was, of course, a phenomenon of the whole of the western world. The anti-establishment mood that came to the boil in 1968 had many underlying causes: the Vietnam war, the American civil-rights movement, the tensions of mutual assured destruction, distrust of the faceless power of multinational business, dissatisfaction at the crass materialism of post-war society, the loss of older metaphysical certainties, a vocal left-wing idealism which defied the evidence of Soviet realities. And so on. But in West Germany, the restiveness had an added, and peculiarly German, twist: externally, the old Adenauerian pro-Americanism had lost its practical or moral imperative in the minds of many of the young. Internally, they wanted an answer to the question about the Third Reich: what did you do and what did you know, Daddy (and Mummy), during those years?

Then came The Holocaust. This American TV series about a fictional Jewish German middle class family and its destruction was screened in Germany in 1979. Done with Hollywood panache and a star-studded cast, it brought home to West Germans, as nothing else had before, the human dimensions of what had been done. Perhaps half the population watched it: an unknown number of East Germans saw it too, illicitly on West German television.

The word itself – holocaust – entered the vocabulary as the descriptor for the genocide of the Jews. There could be no more silence about it, no more gainsaying its centrality in the case for widespread German war guilt. A few extremists might continue to deny its reality, or to downplay its significance. But these met for the most part with outrage or ridicule; and in any event – for the avoidance of any possible doubt – the denial of the Holocaust was made a criminal offence. The public mood changed: from widespread avoidance to widespread confrontation with the facts – and thus to widespread recognition and expression of shame and guilt. That shame, that guilt, is a big part of the reason for the reluctance of the Meister. For all its success, Germany bears a distinctive burden.

German angst follows a venerable German tradition of agonised thought about the meaning of things that goes back several hundred years. In the wake of the Holocaust, Germans have agonised: is it safe – is it appropriate – to have any sense of history or purpose or destiny? And if not, does that threaten a loss of identity? So the angst – the fear of the abyss – remains.

Still, what they agonise about is gradually shifting from the past to the future, to issues that raise their heads everywhere in the new Europe of which Germany is now the centre.

For this Europe is now in long-term relative decline, both politically and economically. Europe is no longer the energetic, ambitious and aggressive continent whose peoples set out over the oceans to plunder, trade, and colonise. It is no longer the continent whose technical brilliance the Chinese emperor Qianlong so notoriously spurned when Lord Macartney sought to open commercial dealings with China in 1793. And it is no longer the frontline of the Cold War. It has retreated from being the centre of the world to being what it had been before the 15th century – a corner of the Eurasian landmass. It remains fertile, populous and wealthy, but it is profoundly uncertain about its identity and its future.

Europe's response to the new reality has been underwhelming. It has been hobbled, first, by the complexity of a Union which now has 28 member states and will have more than 30 within the next 20 years, as the remaining countries of southeast Europe join. There is, secondly, widespread though inchoate disaffection amongst its citizens, who show little sign of any real European loyalty, and who want to be assured of a predictable continuity that is not in fact available.

So is the new European Germany part of a Europe which has in fact no common European future? Are there such fundamental differences of culture and world view that the formation of a coherent European identity has no chance of success? The answer – at least in the German mind – surely has to be: no. For the converse is absurd. Plainly, the concept of Europe is more than just a geographical designation, and the Europeans have things in common that are not in the end overwhelmed by their differences, important though they undoubtedly are. Even the British know that they are different from the Americans. And no one could be under any illusion about the differences between the cultures of Europe and of Asia.

But making a reality of this European vision will prove the sternest test yet for the reluctant new Meister.

Over the past six decades the project has evolved not according to a clear blueprint but in a general direction on which there has not always been complete consensus, and with a considerable measure of improvisation. The future will see more of the same. Somehow, the evolution of the Union is like the construction of one of those great cathedrals of medieval Europe: those who laid the foundation stones knew they would not live to see the completed building, and also knew that the design would evolve as the generations went by. Some of those cathedrals collapsed because they were just too ambitious. Some remained incomplete for hundreds of years. Others were never completed at all. Many of them came close to bankrupting the cities which undertook their construction. Yet many also became structures which were perhaps beyond even the boldest imaginations of those who started laying their foundations.

This reminds us of something about the European project. The Europeans have already been at it for 60 years or so: it has evolved over the years and plainly there is a long way to go. We will not see its completion or its final form in our lifetimes. So will this work? Will Europe be able to become a flexible, cohesive and strong economic and cultural competitor and counterpart to those new Asian giants?

The German answer is clear: building this cathedral is worth the risk and the struggle. Europeans do have a common identity, hard though it may be to define, and even if they only know it by contrast with other cultures. Germans would further argue that Europe has an urgent need – which it can meet much better together than separately – to ensure that it has an economy with enough scale and competitiveness to enable European mind and management to be successful in the global marketplace. So yes, it is worth the struggle.

The implications are, of course, profound. The Union faces the challenge of keeping the plates spinning as the eurozone – which Germany sees as the core of the Union, to which it is existentially committed – is stabilised and consolidated, and as efforts continue to drive implementation of the single market forward. Amongst the main member states, this has deeply unsettling implications for the French, who have historically disliked integrationist ambitions unless reflecting their own world view and built on the premise of French leadership. As for the British, who dislike grand schemes and have a longstanding fear of continental entanglements, they are facing an uncomfortable clarity of choice which they have managed to fudge for half a century.

But for Germany, whose size and centrality had always been such a risk to itself and to others, the implications are easier to accept.

Ironically, they appear on the face of it to put in play the very identity of Germany at just the point in history when it has reached a stable geographic identity and is at peace with its neighbours (so completely that conflict with them is now unthinkable) for the first time. But the whole lesson of German history over a thousand years at the core of the Holy Roman Empire is that its identity is tied only loosely to its polity. Germany is a land where over a long history people have seen themselves as involved in layered identities: the all-important home community or Heimat, the region, and at the same time the German identity which is defined by their culture and their language.

So the prospect of gradual coalescence into a wider framework and adding a European layer to their identity will feel like rediscovering a past which has not, after all, been wholly obliterated. It is much less psychologically daunting than for France. In fact, at one level, it may even be something of a relief, given that the whole experience of Stunde Null has left a deep aversion to any aggressive assertion of national identity. Germans will find this journey much easier than the British or the French.

For what Germans know is that identity is always a composite. It can have many elements: geography, history, culture, language, common interests, and the way societies govern themselves. No single element is necessary to it (the Jews throughout most of their history had no geographic identity, and the Swiss have no language in common). And no single element is sufficient for it (language alone does not ensure a common identity amongst English or Spanish speakers). Crucially, too, identities based on these various elements can overlap. In some cases this is a comfortable mix: in many cases, however, it is a source of potential or actual tension (as shown above all by Jewish experience down the centuries, and now increasingly by Muslim experiences too). For better or worse, it is striking how familiar this complexity is to the German psyche.

This is not to say that for Germany the question of identity will be trouble-free. The country has the third largest number of immigrants in the world – after the US and Russia. Immigrants represent about the same proportion of the population as in France and Britain, but a lower proportion of immigrants in Germany has taken citizenship than in either of the other two. This is, in part, because of a German citizenship law which makes this more difficult, by rarely permitting German citizens to hold other citizenships (unlike both the British and the French). This restrictiveness, which impacts especially Germany's large and well-established Turkish community, sits oddly with that German readiness to live with multiplex, layered identities. At its root, of course, is that deep-seated and long-standing sense that the German identity is embedded in the history, culture and language of a people – an identity which took this form at least partly in the absence for so long of any political unity. In other words, the plasticity of the German identity has its limits. It is better at accepting multiple layers of geographical identity than it is at accepting the impact of newcomers to the German culture (something that the French and the British, for all their differences, both find easier to do). Yet this is inevitable – and the more so, the more the roads of Europe lead to Berlin. So the German journey of self-discovery is not complete yet.

This German journey may be unique and extraordinary. But it has telling lessons for others.

For one thing, 20th-century Germany is not the only example of a country whose relationship with neighbours has been damaged by a sense of past victimisation. Take just one (very large and increasingly influential) example: China has some clear parallels with the emerging power that was the Bismarckian Second Reich. China has a distinct sense of having been victimised and patronised by the West and then brutalised by Japan during the terrible 150 years up to that moment in 1949 when Mao announced that the people of China had at last stood up. And now, just as the Second Reich did in the 19th century, it is taking its rightful place on the world stage.

Or take another particularly poignant example – this time of a small but determined and technologically gifted country: Israel has inherited an all too understandable sense of victimhood because of what happened in Europe and in the face of sentiment in some Arab quarters that it should be wiped off the map. It faces the classic risk that aggressive defensiveness (combined with expansionary settlement policies) aggravates the very hostility it is responding to. Again, this has uncanny echoes in the story of late 19th-century Germany. Again, it would be provocative nonsense to push the parallel too far. But one thing is for certain: Israel has yet to find peace with its neighbours.

And then finally: Germany has looked itself in the mirror and grappled relentlessly with the evils of its past. In doing so, it has been its own most severe judge, and often finds itself shamefully wanting. Yet there was no alternative to the self-torture – given what had been done – and by any reasonable standards this has been a remarkably thorough exorcism. Others have been much less honest with themselves – the Japanese and the Russians, conspicuously. This distorts their self-understanding and contaminates their relationships with others to this day. And there are others too: what, for example, about the failure of the British truly to come to terms with the sins of imperialism or, perhaps above all, with their Irish debacle? To ask this is not to equate one evil with another. But it is to suggest that past wrongs need to be acknowledged and atoned for, if they are not to bedevil the present. And this is surely the profoundest lesson the Germans have for the world.