Through the glinting water of a fountain and the lusty foliage of an Indian summer, the Élysée Palace in the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré looks as elegant as ever. But the gilded gates, chestnut trees and surly police presence cannot hide the fact that amongst the changes of guard, there has been a change of genre. French politics – once remote, dour, resolutely unglamorous – has descended into a shrill farce that preoccupies the nation. In polls and in person, the French will tell you that they only care about serious things like unemployment and the economy, and that personal gossip is for the low-minded Anglo-Saxons. The hefty sales of Valérie Trierweiler's excruciatingly intimate book about life with President Francois Hollande and the circulation boost of weekly magazines that feature any politician's romance, would suggest a different story. To add to the atmosphere of absurdity and hypocrisy, privacy laws, among the strictest in Europe, mean that such magazines often end up in court under laws that were never designed to be used by politicians. Whereupon French judges award damages so low that to publish and be damned has become the mantra of the weekly press.

During a short stroll through the boulevards around France's Presidential HQ, one can see the slide from serious to slapstick. Across the Champs-Élysées, there is a bronze statue of de Gaulle striding purposefully, lanky and heroic. In his life, he gave only one interview, to Paris Match; in the pictures his wife did some knitting and he read a book. He paid part of his own electricity bill at the palace. He set the presidential archetype of old France: financially modest, personally discreet. The press kept a respectful distance from the political class and that class felt invincible.

Posters on a nearby news kiosk show the new realité: they openly mock Hollande and contain former First Lady Valerie Trierweiler's revelations and stories of betrayal from her best-selling book, Merci pour ce moment.

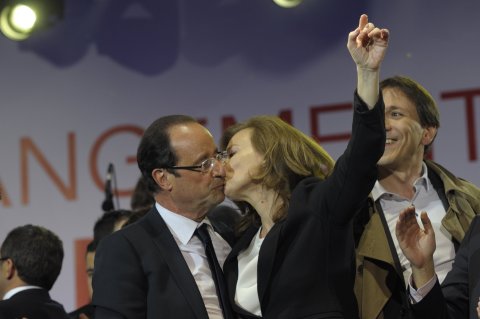

Her account is grief-stricken and furious. Since the photograph emerged of Hollande visiting actress Julie Gayet for a tryst cunningly disguised in a motorbike helmet and mac, he seems like a demonic Woody Allen. Hollande was already the "accidental president," propelled centre stage as socialist candidate in the wake of another scandal – the downfall of Dominique Strauss-Kahn amongst allegations of sexual assault on an employee in a New York hotel. (The charges were eventually dropped.) Up stepped Hollande, whose private life was just as baffling as his presidential predecessor, Nicolas Sarkozy.

The creaks had started with Cécilia Sarkozy, already a second wife on her second husband, running off with another man four months into her husband's presidency (Paris Match had already run pictures of her with her lover in New York, and the editor left). Sarkozy consoled himself with Mick Jagger's ex, the supermodel Carla Bruni. That was dramatic enough – particularly as in classic French vaudeville style – Sarkozy had met Cécilia when he'd presided over her marriage to her previous husband in his capacity as mayor. His new romance was announced at EuroDisney.

From then on, the focus became the money; the private jet lifestyle of President Bling.

So the bedroom door was already ajar, but with the bust-up of Hollande and Trierweiler, after a lot of slamming, it has been firmly flung open. Everyone has crammed in to examine the sheets. Hollande never wanted that; just as oddly as Sarkozy's posing with a wife he'd fallen out with, Hollande didn't ask any of his family at all on inauguration day. He arrived alone and got soaked when he poked his head out of a Citroën's sun roof to wave.

Luc Rosenzweig, of Causeur magazine, says "We don't have the same culture that politicians should be morally correct, but we are getting there. Sexual life used to be a taboo; money was the topic. Big money was disapproved of – even if legally and morally gained. Anglo-Saxon attitudes arrived with the Strauss-Kahn affair which changed it all."

Olivier Royant, editor of Paris Match, agrees that the relationship between France's politicians, its privacy laws, its press and its people becomes increasingly awkward as the Gallic shrug gives way to first-world openness.

The French people have traditionally considered politicians to be sacred, more intelligent than them. They put them on a pedestal. And politicians liked the idea because there are two things they like to keep private, their money and their private life.

Take Mitterand – his life was like a novel, full of secrets. Paris Match revealed the existence of his natural daughter in 1994 and it was a major scandal. A whole life in the shadows. Even then I remember someone saying, "we need to get The New York Times to say we are right to publish this".

The scandal, however, seemed to be as much about publication as about Mitterand himself who escaped condemnation. Journalist Anne-Elisabeth Moutet says "that's because he had class where Hollande has none".

"Then came the babyboomers," says Royant. "Sarkozy came in 2007 and we were in the middle of a modern story. He showed up with the wrong wife in a very bad dispute. De Gaulle and Chirac had political wives who behaved like 'good soldiers', never separating, whatever happened. Now we had these amazing love stories on the job".

"The French people rejected Sarkozy's authoritarian style but they never doubted his ability to do the job. But Hollande's credibility has been questioned. He was meant to be the easygoing, gentle one with a sense of humour."

Trierweiler's book revealed the opposite and made the self-styled Monsieur Normal look like a fraud. It is full of hideous details – such as the way he called her family "not a pretty sight" – too poor to look after their teeth.

"It was like being the courtroom of a divorcing couple," says Royant. "No one has ever seen anything like that – a first lady telling all. Physically he has changed. I saw him at a press conference two weeks ago and his body language is so uncomfortable."

France still hasn't adopted the American and British idea that a man who might lie to his wife, might lie to his country, but they don't like their politicians to look preoccupied. It's not just Hollande, either. Two of his (single) ex-ministers, hitherto only united in trying to keep open blast furnaces in Florange, were recently revealed by Paris Match to be conducting a romance.

Aurélie Filippetti, former Minister of Communications and ex-girlfriend of the rock star economist Thomas Piketty, was photographed arm in arm in San Francisco with Arnaud Montebourg, recently-ousted Minister of Industrial Renewal. This socialist, a lawyer with presidential ambitions, has such a complicated love-life, he seems to fight a one man war against the press to stop it spilling out.

Royant says: "In September there was a crisis at the heart of government and here were two of the main characters together. She quit as minister of culture saying she was following her ideas – actually she was following her love."

"The French newspapers ignored the story we published. Within 36 hours both had said they were suing us. The laws were invented to protect regular people and movie stars but are now used by politicians – Sarkozy, Hollande, Cecilia, Carla – they've all used them. We had to pay €14,000 in May for running a picture of Montebourg and the actress Elsa Zylberstein outside a restaurant."

Zylberstein, just so you know, is an ex girlfriend of Jean Dujardin, who won an Oscar for his role in The Artist. (In France there seem to be about 50 famous people who've all slept with each other, who take part in an ongoing psychodrama.) Julie Gayet asked for €80,000 euros and received €12,000 – a sum small enough to justify publication because Royant, like his fellow editors, believe public interest is more important than the desire for privacy.

To complicate matters still further, Trierweiler, of course, was a Paris Match journalist herself. Royant says they had a complicated relationship – she could no longer properly do the job but still wanted the money. She sent him "bad texts" whenever things appeared about the first couple. He knew she would write a book. "As a journalist she can't stand lies and she was always going to try to analyse what had happened. She revealed details I thought she would keep secret but she met public humiliation with public revenge. Not that it was rational," says Royant.

It seems inevitable that this theatre of absurdity and hypocrisy will be a transitional phase. Royant believes that politicians will be forced to be more open; social networks mean that people are so used to sharing that anything else will begin to look outdated and peculiar.

Journalist Anne-Elisabeth Moutet says: "The French public lie to themselves about what they're interested in. Trierweiler's book is a bestseller, though French TV stations are full of people arguing about whether she should have published it or not. I think she's the new Balzac [as in merciless depiction of contemporary life]. Politicians don't like it and complain bitterly. It's indicative of a real problem; there's a feeling of remoteness and contempt from our politicians who see themselves as royalty. Their sense of entitlement is endless, and the servility to people in power is something you wouldn't believe. It's very unpleasant."

Anything that hastens the end of such entitlement and servility has got to be a good thing. Just don't expect the French politicians – or the people – to admit it.