Sitting in a Hong Kong café, Oscar Lai looks like many of Hong Kong's young people: slight, bespectacled, with an earnest expression. It's only when he gets up does it become clear he's been doing more than focus on his studies recently: He's walking with a limp and is about to see a doctor about his leg and the scratches on his shoulder, which he reveals by pulling down his T-shirt. "That's where the police grabbed me and pushed me," he says.

Lai, a 20-year-old second-year university student, is one of the co-founders of Hong Kong's Scholarism movement, a grouping of mainly high school students that has played a leading role in the city's pro-democracy protests. He burst through police lines outside the Hong Kong government's headquarters last month to reclaim the city's Civic Square for the people after the government fenced off the former protest site.

The police stopped Lai in his tracks, but some 200 others succeeded, of whom over 70 were arrested, including Scholarism's co-founder Joshua Wong—which led to more protests by tens of thousands of young people the following day. When police used tear gas, the furious public reaction led to the start of a wider campaign of civil disobedience known as Occupy Central.

"We are touched by the students' actions," said Occupy's co-founder Benny Tai, a Hong Kong University professor. "We had to respond to the situation. They have encouraged us to start our own action."

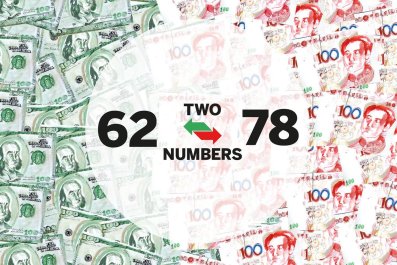

The events have come as a shock to China's leaders, who had hoped that, after 17 years of Chinese rule since the former colony was handed back by the U.K., Hong Kong's young people would have begun to heed their repeated urging to forget foreign influences and begin to "love the motherland." Above all, they hoped to avoid having to put down violently another large-scale pro-democracy protest, as they did in Beijing's Tiananmen Square in June 1989.

Paradoxically, for Lai, as for many of Hong Kong's young people, it was China's attempts to impose a patriotic National Education curriculum on the territory two years ago that helped him find his political voice. It was at that time he and his friends founded Scholarism, leading protests against the curriculum at Civic Square.

"That was the start of the awakening for our generation," he says. "At the start, we were just a handful of teenagers with a shared interest in social issues, but after the protests [which ended with the curriculum being shelved], we felt we didn't want to lose our members, so we turned our concerns to political reform."

Beijing's plan to restrict the long-promised "universal suffrage" for Hong Kong's next leadership election, in 2017, to a vote between "two or three candidates" approved by a committee appointed by Beijing—thus excluding the city's democratic campaigners—has further invigorated the student movement. Now Scholarism has more than 600 members, 80 percent of them still in high school, and many more supporters—and has galvanized the wider society: Traditional Chinese respect for educated young people has come to the fore, as it did in Beijing during the student protests of 1989.

"I really salute these young people," said Joseph Chan, professor of political science, after attending a meeting of University of Hong Kong students about further protests. "They're very courageous and very principled. They are very civil, but they are prepared to risk their safety for what they believe in.

"When I was at university in the late 1970s, only a tiny minority would have taken such action," Chan notes. "At that time, people in Hong Kong still had a refugee mentality [many having fled to the territory from the Communist revolution in mainland China], and were only just beginning to have an identity of their own. But for these young people, Hong Kong is their home, and they feel a need to defend it."

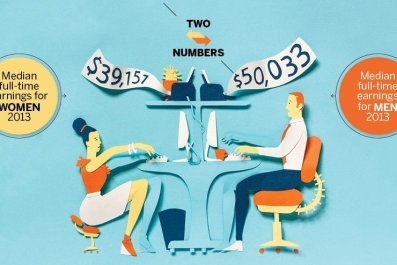

Chan says young people's social awareness has also been spurred by a sense that they face a "gloomy future." "We had social mobility. If you had a degree you could get a good job," he says. "Now there are so many more graduates, so young people don't see such bright career prospects."

"I think many young people have a sense that there is no future, that they can't move upward," Lai says. "They face a lot of pressures. Living costs are high and some go bankrupt because of the student loans they have to take out to pay their university fees."

He is clear about his own identity—he has spent time as a teacher in poor areas of Guangdong province, across the border in mainland China, and he says he loves "Chinese culture—but not the Chinese Communist Party…. I'm a Chinese person from Hong Kong—and I love Hong Kong." Lai says members of his generation have a strong sense of being "masters of their own land" and are committed to fighting for their rights. They feel Hong Kong's older generation of democratic legislators, many of them businesspeople, are "too easily swayed by their own interests, so we have to take action."

There's no doubt that scenes of police firing tear gas at unarmed demonstrators have served to further mobilize some young people. "I felt very shocked and sorrowful," said one Hong Kong university student, who filmed some of the clashes for the university TV station. "We used to respect the Hong Kong police. Are these the same people?"

Rachel Cheung, a 19-year-old student who helped live-tweet the protests for her university magazine, admires the Scholarism activists for boycotting classes. "They care more about society than we did. When I was in secondary school, I didn't know much about politics." She took part in an on-campus demonstration against the National Her own political awakening came earlier this year, when one of her journalism teachers, Kevin Lau, a former editor of Hong Kong's Ming Pao newspaper, was severely injured in a stabbing attack. Many saw this as a triad-style warning to him to stop the critical journalism he had long espoused. "I had heard people talking about Hong Kong's diminishing press freedom for a while," she says, "but when it's someone you care about, you feel you need to act."

Anxiety about issues like press freedom have added to worries about Hong Kong's future in general: A recent survey reported that one in five were considering leaving Hong Kong because of concerns about its political prospects. But Cheung says many of her classmates "really want to guard the city and do something to change things.... Leaving it would be a betrayal."

Not everyone sees civil disobedience as the solution. Rachel says she was initially disappointed when the Scholarism leaders forced their way into Civic Square. And at the University of Hong Kong students' meeting, some said students should focus on their studies. Others said their families told them it was not safe to go out on the streets, so they stayed at home watching events on television.

Two students from mainland China said they had ignored their parents and gone to observe the protests to learn how Hong Kong worked. And one student protester said he felt Hong Kong should stand up for its values not just for itself but to set an example for the rest of China.

"I'm not very confident that these protests can really achieve our outcome of changing the election system," he said, "but when I was studying in the U.K. earlier this year I met a student from mainland China who said, 'Please demonstrate for us. We can't do that in China, but in Hong Kong you can.' So I feel we have to do this."