It is 9.30 on an ordinary Wednesday evening, and the National Express bus draws in to Liverpool coach station after the wearing six-hour journey from London. Within seconds, what would usually be a reasonably organised, even leisurely, unloading process has been replaced by scenes straight out of a television sci-fi drama.

As the driver releases the door, paramedics, seemingly wrapped in layers of plastic from head to toe, run on board and seal an elderly woman into the same sort of protective gear. Panicked passengers rush to flee any which way into the night, jostling and tripping over each other in their haste, shouting warnings to get away. The patient is lifted into one of several waiting ambulances and the vehicle speeds away, lights flashing, sirens screaming.

In due course, a statement from the Royal Liverpool Hospital says that the unnamed passenger who, it appears, was taken ill on the coach and had recently been in an unnamed part of Africa, has tested negative for Ebola. The coach station was closed for a mere half hour or so. Normal life resumes.

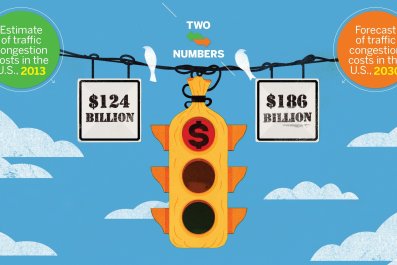

Yet the spectre of Ebola stalks the land. It may be only the latest haemorrhagic disease to be cutting a swathe through a part of Africa, but the World Health Organisation (WHO) reports more than 8,000 cases so far, with more than 4,500 deaths, and no sign that the disease is being brought under control. The charity, Médecins Sans Frontières warns that the number of cases in west Africa could reach 1.4 million by January and, according to Thomas Frieden, director of the US Centers for Disease Control, speaking earlier this month, Ebola represents potentially the most serious international health emergency since HIV/Aids in the 1980s.

For all the famed British sang froid, the frantic passengers desperate to escape what they feared was a contaminated coach in Liverpool show that, even in the UK, fear is but one feverish fellow-passenger away. There are sound reasons why Britain might feel especially vulnerable to this Ebola outbreak, even though the epicentre is more than 3,000 miles away.

Great Britain, and especially London, is a global centre; people are constantly coming and going from all parts of the globe, including from those countries in west Africa – Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea – where the epidemic has caught hold. It also has a 100,000-strong diaspora community from the region. While there are currently no direct flights to UK airports from the afflicted countries, there are 40 flights a week from elsewhere in west Africa, and many passengers arrive in the UK via a third country.

The British Isles, especially the south-eastern corner, are among the most densely populated regions of Europe. For all the elegance of its city squares and the fresh air that wafts around its country houses, many more people live in conurbations, crammed into sub-standard housing.

Commuting, on overcrowded transport systems, is for many a way of life. Generations of children have been brought up on the public health slogan that "coughs and sneezes spread diseases"; the fear of infection is always there.

Medical experts have been categorical that, with Ebola, this is not actually the case. The virus may be especially destructive – with death occurring within 10 days in almost 70% of cases – but it is not transmitted through the air. People have to be in contact with blood or other bodily fluids to contract it. For a tropical disease, the transmission rate is low. In developed countries, with decent public sanitation and hygienic hospitals, the risk of being infected is small.

As of last week, there had been only one case of Ebola in the UK, and it was, strictly speaking, imported and treated in optimal conditions. William Pooley had contracted the illness while working as a nurse in Sierra Leone. He was flown back to the UK in August, confined to a state-of-the-art isolation unit at the Royal Free Hospital in north London and treated with one of a very few doses of an experimental drug – ZMapp – that had been successfully used in the United States to treat two Americans.

Pooley made a swift and seemingly total recovery, and has now returned to work in Sierra Leone, as he promised he would. Before leaving, he flew to the US to donate blood – using antibodies from the blood of survivors to "kick-start" the immune system is one avenue being explored in the absence of a vaccine.

In the speed and seeming completeness of his recovery, Pooley is a poster-child for what modern medicine can achieve in a developed country – and what could be achieved elsewhere, given sufficient money for improved sanitation and suitable drugs. But not all stories out of the developed world have had such a happy ending.

A Spanish nurse, Teresa Romero Ramos, who had helped treat two priests repatriated to Madrid, both of whom died, has only just been given the all-clear after somehow contracting the disease herself. But her husband and several others remain in quarantine, several dozen more are being monitored, and the family dog was put down as a precaution.

MIXED MESSAGES

The record of the US has not been perfect either. Two repatriated aid workers were successfully treated with the ZMapp cocktail of drugs that Pooley received, but a third patient, Thomas Duncan, who was visiting from Liberia, subsequently died, and at least one of the nurses who tended him, Nina Pham, is now in isolation at a special clinic at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, amid allegations of lapses in procedures.

The messages, even from the developed world, are thus distinctly mixed. It may be relatively difficult to contract Ebola in places where the infrastructure is reliable, hospitals are hygienic and staff are well-trained and equipped, but there is as yet no tried and tested vaccine and no treatment. The odds on survival may be infinitely better in the developed world than they are in much of west Africa, but public apprehension is not without reason.

To address this, the UK authorities have pursued a policy of double reassurance. On the one hand they are making great efforts to publicise measures being taken to tackle the disease at source. The health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, addressed Parliament, on 13 October, saying "This government's first priority is the safety of the British people and playing our part in halting the rise of the disease in West Africa is by far the most effective way of preventing Ebola infecting people in the UK." He went on to note the "over 650 National Health Service (NHS) frontline staff," who had volunteered to go out to Sierra Leone, stating that British military medics and engineers were working on a 92-bed Ebola clinic, helping the WHO to train more than 120 health workers a week, and developing laboratory services.

All in all, the UK's military contribution is described as the largest military deployment since the intervention in Libya in 2011.

As a second strand, the UK authorities are transmitting cautious, but comforting, information about the precautions being taken at home. Scarcely an official, medical or otherwise has opened their mouth, without admitting that "it is entirely possible", as Hunt put it, that "that someone with Ebola may come to the UK, but we have very good plans in place. The NHS has a proven track record of dealing with people with Ebola." The chief medical officer, Dame Sally Davies, has been highly visible and often quoted.

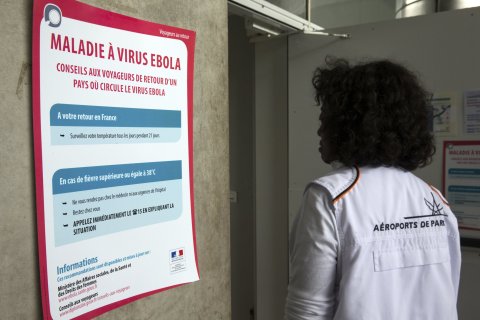

A public information campaign is in full swing. There are signs at UK ports of entry, in doctors' receptions and hospital emergency departments, advising those who have travelled to the affected region and might have a fever to "let a member of staff know immediately". A roadshow has begun touring the UK, appealing for health volunteers to go to Sierra Leone.

The Royal Free Hospital, which treated William Pooley and has the UK's only high-level isolation unit, is on alert. The hospital's special status derives from the laurels it won as the only London hospital to remain open during the biggest 19th-century cholera epidemic. Today, it boasts a specially-designed tent with controlled ventilation, a separate entrance for the patient, separate channels for decontaminating waste, and its own dedicated medical team, but it can accommodate only two people. Three other hospitals – in Liverpool, Newcastle and Sheffield – have units capable of taking Ebola patients should the need arise, but the Royal Free is the most advanced.

Publicity for such facilities encourages confidence. But there are those whose job is to take a more pessimistic approach. Yvonne Doyle, who is London regional director of Public Health England, the Department of Health agency that has taken a leading role in disseminating information in recent weeks, says: "if pockets of London were affected, would we see whole boroughs quarantined? We're not anticipating that . . . but we watch and track very carefully and would adapt our response . . . well in advance of any crisis." "We practise," she said, "all the time."

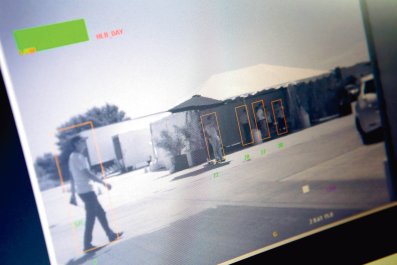

In terms of practice, the biggest and most comprehensive simulation exercise was held earlier this month at just 48 hours' notice. It lasted eight hours and was held at eight locations around the country, preceded by a mock-meeting of the government's emergency committee, Cobra, chaired by the Health Secretary, Jeremy Hunt. Among those chosen for the drills were the Royal Liverpool Hospital, Newcastle's Royal Victoria Infirmary, and the health authority of Hillingdon in north-west London, which is the first port of call for arrivals from Heathrow.

In Newcastle, the Ebola suspect – played, as in the other drills, by an actor, was picked up at an (unnamed) Gateshead shopping centre, where he was quizzed about his symptoms and recent movements, and taken by ambulance to casualty at the Royal Victoria Infirmary, where a team had been alerted to expect a suspected Ebola case. Samples were sent for testing to the government's military science laboratories at Porton Down, and the patient was finally transferred to the Royal Free.

Dr Matthias Schmid, a senior consultant in infectious diseases at the Royal Victoria, who is responsible for coordinating the area's emergency response, supervised the exercise there and said the idea "was to test both the clinical scenario and the public health angle, and how we should respond". This was different, he said, from receiving a confirmed case – and added: "No, we haven't received one yet."

In Hillingdon, the actor-patient arrived at an NHS walk-in centre, where staff passed the patient on to Hillingdon Hospital. As at Newcastle, the emergency team was kitted out in what is called "enhanced personal protective clothing", including rubber boots and goggles, and the end destination was, again, the Royal Free. Graham Hawkes, chief executive of the area's watchdog organisation, Healthwatch, said that, as the person responsible for the borough's capacity planning, he had been one of the few "kind of let in on the secret" – but "only that it would happen, not how it would happen".

In an aside, he said: "There was only one thing they, the staff, were dreading. That they would have to use the decontamination chamber, and that would involve male and female workers naked hosing each other down. Fortunately, we didn't have to do that."

'A COMPLETE WASTE OF TIME'

Unlike other European countries, the UK has also introduced screening at ports and airports, which prompted a degree of controversy. Initially, Public Health England said it had no plans for screening, citing medical opinion that it would have little effect, given the 21 day incubation period for Ebola.

David Mabey, professor of communicable diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, went so far as to describe screening as a "complete waste of time" that would cause huge and needless disruption.

In the afternoon of October 9th, however – the same day that had begun with Public Health England's apparent rejection of screening – the Prime Minister's office announced that screening would be introduced, initially at Heathrow Terminal 1, thereafter at other terminals and at Gatwick airport, and also at the Eurostar terminal at St Pancras station. But when screening actually started, five days later, there was criticism from the other extreme, with some – including arriving passengers – complaining that it was mostly voluntary and not nearly stringent enough. One Briton, who had arrived from Liberia via Brussels, was quoted as saying "I can't believe it was voluntary. They gave me the option, it was unbelievable . . . the immigration officer even shook my hand . . . " Hand-shaking, official guidance later clarified, was discouraged.

There was support for a gentler approach to screening, however, from some academic clinicians, who warned in a study published the same week that too draconian quarantine and screening measures could prove counter-productive, encouraging additional emigration from countries where the epidemic was raging, and subterfuge on the part of those arriving in the UK. Perhaps in partial recognition of this, but chiefly no doubt to allay public fears and prevent panic, the official response in the UK has so far been matter-of-fact and low-key, with reassurance the watchword, frequent reference to medical authority, and an acknowledgement that a few cases – perhaps 10, according to the chief medical officer, might, despite all the precautions, get through.

The tone, content and consistency of the message have met with guarded approval, even from some who are not given to being complimentary about officialdom. Dr Chris Cocking, a specialist on crowd behaviour at the University of Brighton – who has highlighted the dangers of what he calls "elite panic", when the response of the authorities to crises makes matters worse rather than better – said he had been struck by the careful way in which the risks were being set out, and officials' deference to medical experts.

And the chief medical officer, Dame Sally Davies, has four years of experience in the job, while coming across as reassuringly down-to-earth, with a touch of the old-fashioned matron.

Ever since the recovery of the British Ebola patient, William Pooley, however, one aspect of the UK's response has been conspicuous by its absence. While there is only the slightest chance of contracting Ebola in the UK, for anyone who does, all bets are off, because of the lack of either a vaccine or reliable treatment. Asked about the current stock of medication in Newcastle, Dr Schmid said: "There is none . . . . I think that is known." "Hopefully," he said, "we will have 80 – 100 doses by Christmas."

The Department of Health offered little support for such hope, saying that although work was in progress, "there are currently no plans for the use of any Ebola vaccine in the UK" and "the focus . . . must remain on combating the spread of the virus through traditional public health infection prevention and control methods in west Africa".

Trials are in progress, in the UK and recently extended to Africa, of a drug being developed by GlaxoSmithKlein in collaboration with many others, but the only actual success so far has been with the ZMapp drug with which the Briton, two Americans, and now a Norwegian patient have been treated. The drawback here is that Zmapp takes a long time to produce because it relies on genetic modification of plants, and mass production is still a long way away.

For the time being, the public must be satisfied with the two messages being put out about what is being done "over there" and "over here". Any sudden rise in the number of cases in Europe or lapse in the isolation methods currently employed, however, and trust could fade. The image of Ebola in Britain would not then be the relieved smile of Pooley, emerging healthy from his tent, but the panicked passengers who fled Liverpool Coach Station on a recent Wednesday night.