"What is required is required yesterday," said the president of Sierra Leone, Ernest Bai Koroma, at an October 9 meeting at the World Bank headquarters in Washington, D.C. Even before Ebola hit, health care was woefully inadequate in his country. Without an urgent scale-up of health workers, facilities and supplies, the death toll could exceed a million by January in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea.

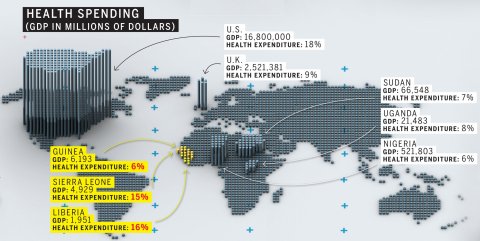

An examination of health, economic and education data help explain why the disease escalated so severely in these three nations; they also show why Ebola won't rage in richer countries and what is required to not only halt this outbreak but prevent it from happening at this scale again.

Ebola struck as Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea were pulling themselves out of the trenches. In Liberia from 1989 and 2003 (excluding a brief interval of peace), a civil war that involved the dictator Charles Taylor and child soldiers gutted schools and hospitals. Meanwhile, in Sierra Leone "blood diamonds" fueled a decade-long civil war with a similar destruction of infrastructure. Guineans became engulfed in their neighbors' battles, and sporadic conflict continues within the country.

Tragedy is not new to this pocket of Africa. For three centuries, the region was slave-trade hot spot; its western, coastal location allowed captors to ship several million Africans to the Americas and Europe, without risking trips into the interior of the continent. Around 1820, the migration was reversed, when England sent freed slaves to Sierra Leone and the U.S. transported freed slaves to Liberia, a country the U.S. government claimed explicitly for that purpose.

With a history of dehumanization followed by turmoil as far back as family histories stretch, people in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea desire peace. In 2011, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Liberia's president, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, for her work on women's rights, among other things. A year later, stability, transparency and prosperity were words on everyone's lips during Sierra Leone's elections—the first held since the end of the civil war without UN oversight. Both Sierra Leone and Liberia launched initiatives to offer free health care to pregnant women and children, and allocated 15 percent of their gross domestic product to health—on a par proportionally with the U.S. and U.K. Political stability made the nations safe for investors, and the countries saw some of the highest rates of economic growth in the world.

"We were rebuilding our infrastructure, increasing our growth rates, enhancing our peace and strengthening our democracy," said Koroma in an address from the Oval Office on September 25. "We were gearing up our compromised health systems to fight the known ailments of our land like malaria and typhoid when Ebola struck."

Ebola hit with a one-two punch. First the virus moved from an animal to a human host in Guinea. Then Ebola reached cities. Had the virus remained in "the bush," as it mainly has previously in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, it might have receded months ago with a lack of bodies to possess. Yet infected individuals traveled to Monrovia, Liberia; Freetown, Sierra Leone; and Conakry, Guinea. In the slums of these capital cities, the sick rested on cots alongside family members in crowded wooden shanties that lack toilets. Or invalids collapsed in narrow, dirt alleys wet with runoff from rainwater, mixed with blood, urine and other bodily excretions that can transmit the virus from one person to another. Ebola is far less transmissible than measles or tuberculosis, which can be caught with a cough, but poverty paved the way for this virus.

Chronic instability has fueled the outbreak in other ways. Few children attended school during the civil wars, and today the majority of adults in Sierra Leone and Liberia have zero education. They cannot read newspapers to learn how Ebola spreads, to understand why—against all emotional tugs—they should force their infected child or partner to die alone from the disease.

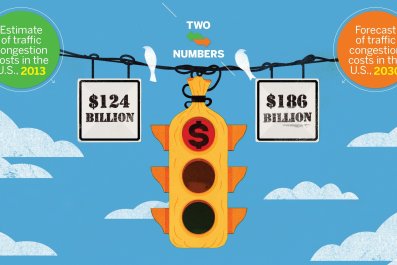

When the last Ebola victim of this outbreak perishes, its effects won't halt. Hard-won reductions in maternal and infant deaths now appear to be reversing, as health workers devote their energy to Ebola instead of malaria and other maladies. Schools have shut down; the economy is at a standstill. The dying don't work, and neither do those afraid of infections they may catch on the job or on the bus to the job. If the outbreak continues past December, the World Bank predicts it may cost these three nations $815 million in lost GDP. It's like war all over again, destroying the foundation countries require for stability.

Recently, world leaders promised their support for new, operational clinics. These would provide a system needed to slow the disease; the capacity to deliver Ebola drugs and vaccines as they become available; and the infrastructure to treat other diseases down the line—if the developments last. "The worst-case scenario is that everyone picks up the stakes and leaves," says Tim Evans, director of the World Bank's health, population and nutrition department. If that happens, history will repeat.