Last December 2, in the tiny southern Guinea village of Meliandou, a 2-year-old boy named Emile developed a fever. Soon, he was suffering with black diarrhea and vomiting. Four days later, Emile died and became the first fatality from the current Ebola epidemic that is shaking the globe. Emile was just one of the millions of invisible Africans who mostly seem so distant and disconnected from the industrialized world. But while America ignored his life not so his death.

Now that Ebola has reached the United States, too many Americans are quaking in irrational fear while trying to decide who to blame. Many Republicans moan that President Obama has left the country at risk by refusing to shut the borders to people from African nations—a foolish and cynical attempt to rile up voters with a proposal experts said would likely lead to untraceable movements of infection and, ultimately, an explosion of illnesses in the U.S. Others are slamming the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, which has been warning for years about the growing threat of infectious disease but has been largely ignored. Still others sneer at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas, where the first Ebola patient in America died, while overlooking the slashed budgets for Texas hospitals and the reality that doctors in this country were unlikely to declare that someone with flu-like symptoms had a deadly disease perhaps never seen in the United States before.

In other words, Americans are wasting time arguing instead of acting. Who is to blame? All of us, for being too distracted or too uninterested or too caught up in politics to intelligently address the real health threats this country faces. And if the U.S. is finally forced to wake up to that fact by an overblown, senseless hysteria about Ebola—which, because of the difficulty of transmission, will likely kill fewer Americans than the number who will die on our highways while you read this column—so be it.

Start with the cliché: Globalization has made this a much smaller world. Countries that once had little direct connection to Western industrialized nations are now in daily interaction with them. More and more people travel from one country to another for work. Others travel to visit them. Cargo comes from all over the world. Whatever parasites or viruses that emerge in one country can now travel quite readily to another—whether inside a person or in shipments with objects containing feathers, animal skins used for leather, or an endless array of other seemingly innocuous items.

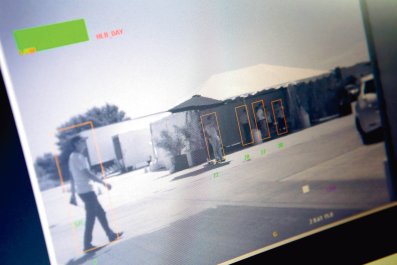

The first line of defense inside the United States is composed of the 20 quarantine stations operated by the CDC that search for potential health threats among the millions of people and untold millions of tons of cargo arriving each year by planes, ships, trains, trucks and cars. Infectious disease experts say that health threats come through shipping ports and airports into this country every day, and the government doesn't have the money or manpower to identify all of them. Moreover, it is not feasible that the quarantine stations, even with double or triple the budgets, can become an impenetrable shield blocking the importation of disease. Consider this: America imports almost $40 billion of goods from sub-Saharan Africa and ships $63 billion of goods there. Are members of Congress willing to cause a global economic crisis by blocking all trade with Africa just so they can rip President Obama for following the advice of experts?

The Ebola hysteria has come about largely because two Americans—both nurses who cared for an infected man visiting from Liberia—contracted the disease. At the time of this writing, no U.S. resident has died. However, some 2 million Americans are infected each year with antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and, of those, 23,000 will die. That's millions of infections, and tens of thousands of deaths a year, yet there is no wall-to-wall cable news coverage of that, no demagogic politicians pounding the table. A resistant bacterium that causes largely untreatable urinary tract infections that emerged in New Delhi made its way to the United States, but where are the calls for keeping out residents of India?

Also think about this: Once the United States starts closing its borders to an epidemic that has not killed a single resident, how will American politicians convince other nations to keep their borders open for us, since "our" diseases have killed tens of thousands more people in the Western world than Ebola has. One such global epidemic the political spoon-bangers missed involved a drug-resident bacterium called Clostridium difficile. The first outbreak occurred in the United States, then was transported by Americans and domestic cargo to Switzerland and South Korea. Soon, a new strain appeared in Canada, then spread throughout North America, before jumping to Australia and Europe. Finally, it spread to Asia. This disease is killing 14,000 people a year just in the United States and American bacterial outbreaks have been traced directly to surging epidemics in the United Kingdom. And yet not a single European politician is demanding that their borders be closed to Americans, perhaps because they are more inclined to listen to the experts than are blatherers on cable news programs. Nor did any African countries, most of which escaped this murderous epidemic that the United States propagated through its reckless overuse of antibiotics in both people and livestock.

There have been other epidemics that rapidly spread in recent years, threatening global security: the deadly SARS pandemic of 2002 and 2003, which started in China but then quickly spread to 37 countries, including the United States. Dengue fever, a mosquito-borne disease that causes about 25,000 deaths around the world annually and was long restricted to Asia; in recent years, for the first time, it was reported among residents of Florida who had not traveled overseas.

The H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009 started Mexico, then spread to United States, and rapidly jumped from there to more than 200 other countries. In just the first year of that pandemic, 274,304 Americans were hospitalized and 12,469 people died, according to the CDC. Worldwide, somewhere between 151,000 and 575,000 people died. (That compares to about 4,500 deaths all over the world from the current Ebola outbreak.) The reason for the difference in fatalities there? The disease that came out of America was extremely easy to transmit, while Ebola is not. But even so, during that pandemic, no one called for closing the borders to Americans.

Nor should they have. There are hundreds of diseases, many of which are far more deadly and communicable than Ebola. If we follow the hysterical advice of know-nothings, the only way to stop the importation of viruses and bacteria at the border is to throw plastic sheeting over America, then prevent anyone and anything—residents, tourists, cargo, business travelers—from coming or going. Basically, create a real-life version of the book and television show, Under the Dome.

Or, Americans could grow up and start discussing ways to solve these problems, instead of dreaming up ideas that transform epidemiology into politics. We should follow the advice of infectious disease specialists and combat diseases at their source. Rather than pretending African or Asian or European epidemics will never reach American shores, Washington, D.C. should lead international cooperation to stop them.

The CDC last year included in its budget a request for $7.5 million to establish national public health institutes in developing nations. This was inspired by tours of Africa by infectious disease experts who saw that significant fragmentation in these countries, with different departments handling things in different ways and failing to determine when an outbreak was occurring, where it was and how it was spreading. When one person contracts a serious communicable illness in the United States, the CDC learns about it within, at most, a few days, through a reporting system. When Emile contracted Ebola, the disease spread from town to town and country to country for months until it was finally recognized by African agencies and reported to the World Health Organization.

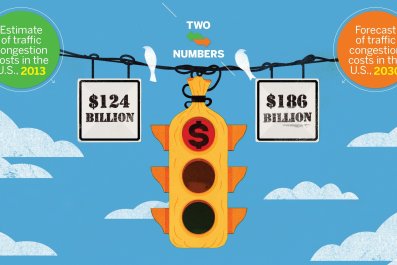

The money required to set up an international network of health institutes that mirrors the operations and techniques of the CDC is less than the median annual income for a single American CEO. Yet Congress zeroed it out of the budget in an orgy of spending cuts. Overall, the funding to meet pandemic threats has been cut from $201 million in 2010 to $72 million this year.

The next rational step would be to recognize that infectious disease is a greater national security threat than ISIS, Al-Qaeda and every other terrorist group combined. While there is a danger that some lunatic somewhere will intentionally bring a deadly virus to America, the bigger threat of a biological attack comes from that historically relentless terrorist, nature.

This is why the military has played an increasing role in combating epidemics over recent decades. While gasbags like Representative Louie Gohmert, Lunatic Party-Texas, prattle on about how terrible it is for Obama to have sent troops to help combat the Ebola outbreak in Africa, people with basic knowledge of military history know that epidemics and potential pandemics were long ago identified by the Pentagon as significant threats to national security that, at times, require a response by the armed forces. The military has played a role in overseas health projects since 1898, and that role grew significantly during the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations after the intelligence agencies declared HIV in sub-Saharan Africa to be a national security threat. The SARS and H1N1 pandemics increased awareness of the threat, and with that came military strategies for how to address it.

Add to this the exceptional and almost criminally underappreciated Army and Navy overseas medical research laboratories. They helped develop the first vaccine for the Japanese encephalitis virus; identified a new strain of dengue fever in Peru and contributed to the prevention of wider epidemics; and isolated the Rift Valley fever virus, which caused serious outbreaks in Kenya, Somalia and South Africa in recent years. Yet these incredibly lean yet important facilities also face regular budget cuts.

Which bring us to the most important initiative of all: the Global Health Security Agenda. Unfortunately, this is an Obama initiative, which means Republicans in Congress will most likely oppose it reflexively. Obama first advanced the proposal in a 2011 speech at the United Nations that highlighted the security threat presented by infectious diseases to nations throughout the world. The plan, while complicated, is intended to create global cooperation in preventing, detecting and responding to outbreaks before they become epidemics. Already, the G7 has endorsed the plan, the United States has committed to aid 30 countries over five years to achieve the goals of the program.

In other words, there are rational adults out there doing serious things to confront the threats we face. And while too many Republicans are using the Ebola epidemic to rant nonsense, there are others focused on policy. Probably the best and most serious politician in both houses of Congress on this security issue is Representative Christopher Smith from New Jersey. Few will see him chattering on the latest cable blab-fest because he will be, like Obama or Tom Harkin in the Senate, working on the nitty-gritty policy developments that will make this world safer.

Preventing infectious disease is important business. If humanity perishes, chances are an infectious disease will be the culprit. The issue is too important to be used as a political bean bag tossed about by knaves and fools. Americans should be demanding far more from leaders who seem too cynical, too ignorant or too disinterested to focus on policies rather than politics. Sound bites won't keep us safe from an epidemic. Inoculating ourselves from partisan debates just might.