A faded blue-gray sedan roars into the gravel parking lot and pulls up beside me.

"You here for all the political shit?" the driver, a bony man wearing faux Oakley sunglasses, asks through his half-lowered window, a cigarette hanging from his lower lip. "You know what all this is about? All these Hasids have their own private places around here. They've got their own camps and shit. They run off their rabbis, and they pull off their drug deals. And the state police can't go on the properties because they're 'religious.' That's where all the fucking deals take place. You know what I'm saying?

"That's just something for your noodle," he adds, twisting his head left, then right. "But you haven't got my name or number, or anything." He slams his car in reverse and punches it, small rocks popping under his tires as he pulls back onto the road.

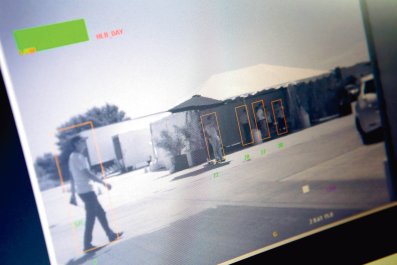

It's a little before noon in Bloomingburg, New York, a small Catskills hamlet (pop. 420), and I'm pacing around the village hall, waiting for the polls to open. All morning, both residents and concerned locals (the village has only 361 registered voters) have been staking out spots 100 feet away from the polls—the mandatory minimum distance for politicking. A man sits across the street with a roster of the registered voters; he's watching who goes into the hall, checking off names. He seems to know everyone by sight. Another man a camera takes photos of everyone voting to prevent fraud, he tells me. On the corner of this two-lane thoroughfare and Main Street, several women hold signs urging passersby to vote 'yes.'

The residents of Bloomingburg are voting to dissolve their village. If the resolution passes, the town of Mamakating, of which Bloomingburg is a part, will take over the village's operations. The dissolution issue dates to 2006, the year Bloomingburg annexed land to a local developer. There are many versions of what happened, but the gist is this: The developer told village officials he envisioned a subdivision with 125 luxury townhomes as well as an 18-hole golf course, pool and clubhouse open to all villagers.

The developer wanted the project, called Chestnut Ridge, to be part of the village because its zoning and building permitting processes were more relaxed than those in Mamakating. To further sweeten the deal, the developer offered to repave Main Street and build a $5 million sewage plant for the village—projects which were in fact completed. The village board agreed. Over the next few years the plan morphed into 396 townhomes and no golf course. The local developer is no longer involved and has since said that he signed a confidential agreement with Shalom Lamm, the project's real developer, to serve as the face of the project during the annexation process. Some locals suspect Lamm hired a front man because he is the son of Rabbi Norman Lamm, who served as Yeshiva University chancellor, and is thought by some to be a "Hasidic developer"—that is, one who develops housing marketed specifically to the Hasidim. (Lamm, who practices Modern Orthodox Judaism, denies this.) Locals allege Lamm has bought a quarter of Bloomingburg's non-Chestnut Ridge real estate. Now, many of the nearly 150 new Hasidim there live in Lamm-owned homes. In addition, the local developer has admitted he told locals the development would have 125 homes when he knew it would have far more.

In July 2012, residents of Bloomingburg and the greater Mamakating area formed the "Rural Community Coalition" to oppose Chestnut Ridge. The coalition sued to stop the development, alleging the village's approval of the project was invalid, but a judge dismissed the suit in April 2013. By November 2013, Bloomingburg had granted Chestnut Ridge building permits for 126 townhomes. So far, 50 have been built. (They are being officially marketed for the first time this week, so they are presently unsold and empty. A representative for the developer told me the final touches, including landscaping, weren't ready until now.)

Since litigation didn't work to stop these units, opponents petitioned the village to hold a dissolution referendum. They hope that if Mamakating takes over Bloomingburg's operations, its stricter planning processes will shut Chestnut Ridge down.

Hence the question: Is the referendum a growth-slowing measure or an anti-Hasidim ploy?

*

Bloomingburg, some 70 miles north of New York City, has one traffic light. The mayor and village clerk's "offices" are just two desks placed side-by-side in Bloomingburg's lone courtroom. In this onetime gateway to the Borscht Belt the fall trees are brilliant hues of red, yellow and orange. It was just the kind of place Yankel, a 63-year-old Hasidic man from the bustling streets of the Borough Park neighborhood of Brooklyn, had always dreamed of retiring. And so he did. (Yankel is not his real name; he requested a pseudonym for reasons that will soon be obvious.)

Yankel, a Hasid who as a matter of course wears a black suit and coat, as well as the long, curled side-locks, called peyot, dangling below his dark yarmulke, says he was walking down Main Street a few months ago when a car pulled up next to him. "Jew!" the driver screamed.

"I told him, 'You must be a genius! How did you know I'm a Jew?'" Yankel told Newsweek.

"I'm glad they used that name," Yankel says as he and his wife of 42 years relax on the expansive porch of their Bloomingburg home, which is not in Chestnut Ridge. "It's a lot kinder than I've heard before."

For the backers of Chestnut Ridge, stories like Yankel's demonstrate that opposition to the project is rooted in anti-Semitism. On September 8, 2014 the project's developers and several Hasidic residents of Bloomingburg filed a $25 million civil rights lawsuit against the village and the town of Mamakating, alleging that nobody in Bloomingburg had a problem with Chestnut Ridge until false rumors circulated in the summer of 2012 that the development is exclusively for Hasidim. (An ad for Chestnut Ridge which ran October 7 in the Times Herald-Record newspaper, which covers the Hudson Valley including Bloomingburg, does boast that neighborhood amenities include "houses of prayer and institutions, including a synagogue, post-marriage learning center and spas"—alongside a house-shaped graphic with the words "equal housing opportunity.")

Residents have honked and hurled coffee cups at Hasidim, the lawsuit charges. A building inspector ordered a group of some 100 Jewish students out of a building during their prayers this summer. He threatened to call the state police if they didn't leave "within 10 minutes." And a man from a nearby village smashed the windows of a new kosher pizza shop five times this summer. Owners of the property next to Chestnut Ridge erected a 20-foot wooden cross in late 2013, and Hasidim interviewed by Newsweek said they have been followed and photographed while heading to shul.

When Bloomingburg's planning board denied a permit request to convert a former garage into a religious school, Lamm sued. After the New York Supreme Court demanded the board reconsider the application, the village's board of trustees dissolved both its planning board and its zoning board of appeals, and imposed a building moratorium. Less than a month later, the village clerk certified a petition to dissolve Bloomingburg. The referendum was scheduled for September 30, 2014—in the midst of the Jewish High Holidays.

*

Clifford Teich, an affable man in a pale blue lab coat and white sneakers, describes himself as, "the last of the country doctors." Teich, 61, has had his Bloomingburg practice since 1982. His roots here are deep: His father owned a Borscht Belt bungalow colony nearby, and Teich spent his childhood summers there. He describes himself as neutral with regard to the present conflict. Teich, who was deputy mayor in 2006, voted to annex Chestnut Ridge. But now, he opposes both the development and dissolution of his village.

He says he was tricked into voting for annexation. The local developer pitched him 125 homes, Teich says, not 396. Teich, who is Jewish, also feels he was duped about the type of community he voted to annex. He never wanted any one group of people to dominate Bloomingburg, whether the group be white, black, Puerto Rican, Filipino or Hasid. Many residents say they oppose Chestnut Ridge because they feel similarly duped—not because of the religious beliefs and practices of the newcomers.

Still, Teich admits, "Being Jewish and Hasidic—and they are a strange lot—doesn't help their situation. I mean, they are strange. This is now, I call it, Kiryas Joel North," he says, referring to a large Hasidic community south of Bloomingburg that some call a theocracy. "It is the same thing; they're taking over."

Holly Roche, Rural Community Coalition president, who is also Jewish, insists the opposition isn't anti-Semitic. "We're anti-corruption and anti-crime, period," she says.

In March, FBI agents raided 20 Lamm-owned properties in Bloomingburg, including homes and his offices, to see whether people who registered to vote at those addresses live there, Roche points out. Lamm's detractors claim he moved Hasidim to Bloomingburg to build a voting bloc sympathetic to his development plans, multiple media outlets including The New York Times reported and the Times Herald-Record reported. An FBI spokesman told the New York Times agents were "conducting multiple searches in the Bloomingburg area in relation to an ongoing investigation." The FBI wouldn't comment on the present status of the investigation.

Bill Herrmann, Mamakating's town supervisor, also denies that opposition to the development is about Hasidim. "I never said, 'I'm not letting Jews move into my community,' or whatever," Herrmann says. Twenty-four percent of Mamakating residents are Jewish, he adds, and "most" are against Chestnut Ridge.

According to Herrmann, the opposition is about "lawlessness"—he and others allege the developer wants to flout important building codes. He and like-minded townspeople oppose the school because it's "a metal building without a sprinkler system," he says. And yes, a building inspector did ask 100 Jewish youth to leave a building during morning prayers—because the building was over capacity and didn't have a fire suppression system.

"We're worried about the safety of the children, but it's 'anti-Semitic,'" Herrmann scoffs.

*

Perhaps the only undisputed statement one can make about Bloomingburg these days is that it's a mess. Even the referendum results will remain undecided for at least a month, because so many voter registrations have been challenged in court—a move that was challenged by the challenged voters.

It's also important to note that this mess is part of a bigger conflict involving Hasidic communities. Kiryas Joel, a Hasidic village of approximately 21,000 about 25 miles away from Bloomingburg, has been embroiled in controversy since the mid-1970s, when members of the superconservative Satmar sect began buying land there. Joel Teitelbaum, grand rabbi of the Satmars, wanted to create an isolated community outside of the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn, where he and his followers had settled after the Holocaust, explains David N. Myers, UCLA history department chair and professor. He and Nomi M. Stolzenberg, University of Southern California Law School professor, are writing a book on Kiryas Joel.

Monroe, New York, incorporated Kiryas Joel in 1977, due to frequent zoning disputes between the incoming Satmars and non-Satmar community around them. Kiryas Joel recently made headlines for putting up sidewalk signs segregating male and female pedestrians. (Community members maintain they are suggestions, not mandates.) This comes less than a year after the New York Civil Liberties Union sued Kiryas Joel for a gender-segregated public playground. Kiryas Joel settled that lawsuit in March, agreeing to remove the red and blue benches and play equipment segregating the sexes.

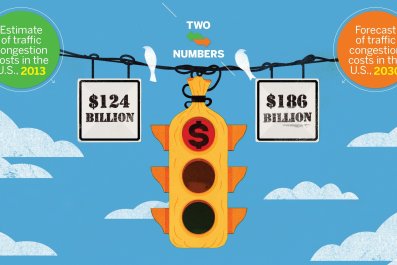

Hasidim living in Monroe also recently bristled that Kiryas Joel leaders created a map identifying Hasidic-owned land in the area, which was posted publicly on a municipal website. Kiryas Joel officials said they made the map to pinpoint which land the village should target in its annexation petition. (Hasidim prefer to live near one another, as they cannot drive to and from religious services on the Sabbath.) One Satmar who was raised in Kiryas Joel told the New York Post that the map "reminds all of us of the 1940s, when the Nazis did exactly this—an account of every Jew, and their businesses." The map was removed due to numerous complaints. Residents protest that further annexation of the high-density enclave will ruin their rural quality of life and property values.

About 50 miles from Bloomingburg, Hasidim and their neighbors have also been embroiled in a decade-long battle, this one regarding the East Ramapo Central School District. Seven of the nine school board members there are Hasidic, and their children attend private yeshivas, not public schools. Residents of the mostly immigrant and minority district allege the school board has stripped the district of funding for schools to keep taxes low.

Meanwhile, several Jewish families are suing the Pine Bush Central School District, which is about five miles from Bloomingburg. They allege school officials did nothing to stop ongoing bullying of Jewish students, including swastika graffiti and Nazi salutes.

Of course, what has happened near Bloomingburg between Hasidim and communities does not mean the same thing will happen in the village. Nevertheless there is no indication that the tensions will lessen anytime soon. Hasidim tend to have seven or eight children per family, meaning their communities (and voting power) will continue to grow. According to the Times Herald-Record, the most recent data available indicate that Kiryas Joel grew at an annual rate of 2.8 percent between 2010 and summer 2013—far more than anywhere else in the region. And in Bloomingburg residents will continue to ask themselves, whose village is this, anyway?