In 1995, while a law student at Israel's Bar-Ilan University, Nitsana Darshan-Leitner and fellow law students were incensed that Muhammad Abbas, one of the Palestinians who took part in the hijacking of the cruise ship Achille Lauro in 1985, was to be allowed to return to Israel. The students decided to take their own case to the Israeli Supreme Court.

Unable to afford a lawyer, the group chose Darshan-Leitner to represent them and argue their case. "The reason they chose me was simple," she explains. "Because I am a woman. If I lost, they figured the court would be nice and I would not be slapped with court fees."

Darshan-Leitner had never argued a case before. "I was scared out of my mind," she said. But her rhetoric was fiery, evoking the miserable plight of Leon Klinghoffer, the elderly disabled Jewish-American in a wheelchair who was shot and pushed overboard by the terrorists when their demand for the release of 50 Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails was not met. "I said Klinghoffer's voice could be heard from the bottom of the ocean," she says. "It was very dramatic."

Darshan-Leitner lost the case, but the jury was so impressed by her delivery and passion, it quoted her summation while reading its verdict. "I didn't have to pay court fees, either," she says. But the case gave the young lawyer the appetite to go after other seemingly impossible causes—in particular, suing terrorists for compensation.

Earlier this month, Darshan-Leitner and her team at Shurat HaDin, Israel Law Center—some of whom are the original law students from Bar-Ilan—began a major investigation and lawsuit against the terrorist group Islamic State, also known as ISIS. They say that if they can trace the money ISIS is receiving from oil sales, they can halt their operation. The route to this, Darshan-Leitner says, is by following the banks that still deal with ISIS.

"The question is, How does ISIS get the money?" Darshan-Leitner, who is in her 40s, says from her Tel Aviv office. "We can't technically go after ISIS. But we can go after the Arab banks that finance them. The money source. We are not talking peanuts—we are talking about several millions of dollars a day ISIS gets from oil fields. There must be banks that help ISIS receive that money. This is what we need to put our fingers into."

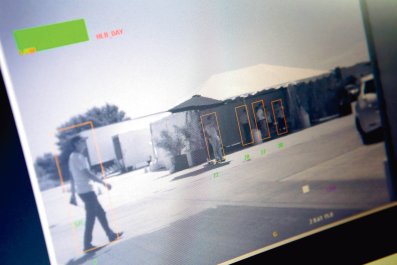

While she can't go into specific details of the ongoing investigation—whether, for instance, the CIA is helping her and what banks she is targeting—she says that her team will try to interview workers who are employed at the oil fields. "We have terror experts, and we definitely have leads," she says.

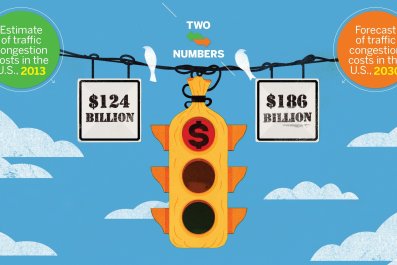

"Black market just means prices. Money must go through a banking system. And that's where we look." She says ISIS is making roughly $1.2 million "per oil field, per day. And they have seven oil fields." The banks, she says, are mainly from Qatar and Turkey. "The Saudis learnt their lesson. We aren't looking into them."

"Remember that when ISIS took over the oil fields, they kept the same local workers and are selling to the same people," she says. "They changed the management—they put in their own guys—but they sell to the same people, the same gas stations. They sell in Turkey and Iraq—and here's the real irony—to Assad's government in Syria."

As for getting assistance from the U.S. or Israeli government, "I can tell you from past cases, once you touch the nerves of the security services, once they know you are going after terrorists, they realize you have a tool to fight them. They jump in and help you."

Her strategy in attacking the terrorists in their pocketbooks is to use legal loopholes to block their funding. If the banks they use have branches in the U.S. or Canada, she can prosecute them under the Patriot Act and the Canadian Anti-Terrorism Act. Citing past cases, she explains that whenever there is a terrorist attack, her team starts by checking who has been arrested and then begins to slowly build up a case.

"The case tells you who committed the crime. But the goal is to go after who funded the terrorism," she says. "Not the terrorist himself, because that would not deter him. Nothing would deter him, certainly not lawsuits.

"All the banks [the terrorists use] have transactions in hard currency. They usually use a corresponding American bank. Then you can file a case in the U.S." It can still happen if the bank has a branch in another country, she says. "For instance, we filed a lawsuit against Hezbollah by tracking a Lebanese bank that had ties to Canada. The court used their long-arm status and applied jurisdiction to that bank.

"Then we follow the money. We follow any clues that connect the perpetrator to the source. The other way to investigate is to take the whole organization, which is much harder. We use one victim and file a civil lawsuit." This, she says, is her way to the heart of terrorist organizations—their most vital life source: their money.

The idea to "go after ISIS" came during the summer, when the Gaza war was raging. "We were going after Hamas," she says. "The reason the war broke out was that Hamas ran out of funds, even though Qatar agreed to give them money. The problem was, no bank would wire it to them. And this was because of us. Banks are afraid to be sued if they operate in terror zones."

Initially, she says, money to Hamas was smuggled in suitcases, in cash, through the tunnels linking Gaza to Egypt. Then the tunnels were destroyed. In the course of reviewing the Hamas case, her team realized there were Qatari banks providing specific transactions to Hamas. The team began linking names of account holders to terrorist groups. "We expanded the operation when we realized they were wiring to other terrorist organizations, like ISIS."

Going after ISIS, she admits, is "challenging." Aside from the fact that its structure is murky, it operates out of Syria and Iraq, two countries whose banking systems are not accessible. "Even Al-Qaeda and their commanders had bank accounts you could trace," she says. "But with ISIS, you lose the trail."

She claims, however, that the team is not daunted. The office, which is now composed of 10 lawyers, opened in 2003. Since then, Shurat HaDin has brought civil actions against numerous banks and financial institutions accused of "aiding and abetting Islamic and Arab groups engaged in terror attacks."

Past cases have been conducted against the PLO, the Palestinian Authority, Hezbollah, Hamas, the Republic of Iran, North Korea and the Bank of China. Some are more successful than others. Darshan-Leitner says her firm has succeeded in receiving more than $1.5 billion in judgments, freezing over $600 million in terror assets and securing over $120 million in actual disbursements to the victims and their families.

She doesn't just represent Israelis. "We have a lot of Arabs, Christians and Muslims, and Druze—for instance, a case we have now against American Express in the North." (This involves a suit in which Darshan-Leitner and a New York attorney, Robert Tolchin, allege that American Express Bank and the Lebanese Canadian Bank executed millions of dollars in wire transfers to Hezbollah between 2004 and 2006, and that the money was then used to carry out rocket attacks on Israeli cities.) She also launched a public campaign to save the life of Imad Sa'ad, a Palestinian police officer accused of having assisted Israeli intelligence services in hunting down fugitives. He had been sentenced to death by a Palestinian military tribunal. "In the end, he did not die. He was sentenced to hard labor in a prison," she says.

But she would not, she says, represent the family of the murdered teenager, Mohammed Abu Khdier, who was kidnapped, tortured and burned alive last summer in a revenge attack by hard-line Israeli settlers retaliating against the kidnapping and murder of three Israeli teenagers. It was a horrific case that stoked Israelis' conscience and forced them to examine their treatment and reprisals against Palestinians.

Why? She thinks for a moment, then says, "Many groups represent Palestinians. But we are the only ones who represent Israeli victims of terror as an organization. There are some lawyers who take a case here, a case there, but not the massive way we do."

She recently filed a proposal for an indictment accusing Hamas of war crimes, to try to bring it to the International Criminal Court—which, even by Darshan-Leitner's terms, is a long shot.

But there were other long shots. In 2002, her team went after the former Syrian defense minister, Mustafa Tlass, one of the most famous men in Syria aside from Bashar Assad, on behalf of the Shatsky family, whose daughter was killed in a pizzeria in the Karnei Shomron settlement shopping mall in northwestern Samaria, east of Kfar Saba, by a terrorist group she says was funded by Syria.

She filed suit in Washington against Syria, contending that it provided critical support to the militant group Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, whose members carried out the suicide bombing attack. The case is still pending.

Darshan-Leitner's lifestyle is hectic. She is married to an American law lecturer from Miami, Ariel Leitner, and has six children, ages 6 to 15. "It's crazy, it's insane," she says. "I travel a lot. I get to the office sometimes at 6 a.m. and leave at midnight. But I am very attentive to the kids on the weekends and strict about their homework."

Her parents, who were born in Iran and arrived in Israel in 1948, as the new state was emerging, help out at her North Tel Aviv home, as does a nanny. She does not live on an illegal settlement and says she is "religious—Orthodox, but not ultra-Orthodox." Even so, she admits her views are fairly hard-line. She is convinced that there will never be a two-state solution in her country. "I don't think we can live together," she says bluntly.

As for her current case—ISIS—which is consuming most of her time, she is philosophical. She says that she is doing it not just for Israelis and their protection, but for the entire international community who are at risk of ISIS's murderous ways.

"Of course it's a challenge—I use that word a lot. Not only because of the nature of the case but the danger it poses to the rest of the world. This is not local terrorism—not Hamas or Hezbollah or the PKK [the Kurdistan Workers' Party] threatening the Kurds."

"If we block their funding, it will be extremely important in the fight against terrorism."