"This is an attempt to knock London off its perch," declared the colourful Conservative mayor, Boris Johnson. "We're not going to let it happen." And that, in effect, is how the political game over the European Union's cap on bankers' bonuses has played out so far, after 18 months of rhetoric, legal argument and financial ingenuity.

A measure introduced by the European Parliament, with the declared aim of reducing risk in the financial sector – and the undeclared aim, perhaps, of punishing bankers for their role in the financial crisis and subsequent lack of remorse – stands accused by its targets, the bankers, of increasing risk and instability in their businesses.

Johnson has called it "possibly the most deluded measure to come from Europe since Diocletian tried to fix the price of groceries across the Roman Empire . . . it's not just hostile to the greatest financial centre on earth. It's hostile to growth across the EU. The most this measure can hope to achieve is a boost for Zurich and Singapore and New York at the expense of a struggling EU." Lack of UK political support for the cap has meanwhile encouraged banks in London to make no secret of their use of pay mechanisms that circumvent it.

Johnson, who is now about to re-enter parliament, and likely to be a favoured runner in any forthcoming contest for the Conservative party leadership, made his "Diocletian" speech back in March 2013, shortly after Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne had been defeated 26 to one by fellow EU finance ministers in an attempt to overturn the bonus cap, which the European Parliament had insisted on adding to a package of other less controversial prudential banking rules proposed by Brussels officials.

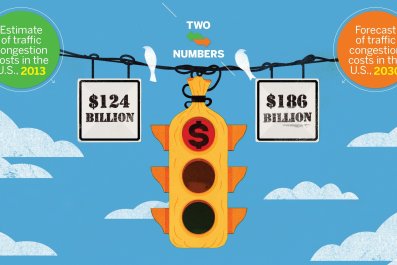

Osborne has maintained his campaign ever since. In diverting time and Treasury resources from other pressing economic issues to oppose the cap, the Chancellor knew he risked jibes from his Labour opponents and the media about defending his "millionaire City pals", some of whom are also Tory donors. But he insists his stance is a principled matter of resisting unwelcome and ill-designed regulatory interference from Brussels – particularly in the financial sector, which represents 10% of UK economic output.

In September this year, the UK government brought the case to the European Court of Justice, claiming that the cap is invalid under EU law on several grounds including contravention of the Lisbon Treaty. A ruling from the court's Advocat General Niilo Jaaskinen is awaited in November, but few commentators expect the UK plea to prevail. Meanwhile, the European Banking Authority has declared the circumvention of the cap by payment of so-called "role-based allowances" (which increase the variable element of bankers' pay packages) by some 39 banks to be a breach of the spirit of the cap rules, and has set a deadline of 31 December for the banks to fall into line.

The rules of the cap in fact capture a wide sweep of European financial activity, not just what happens in the City of London – though that is where, if strictly applied, it bites deepest, simply because that is where by Europe's greatest concentration of high earners go to work. The cap limits bonuses to 100% of base salary unless shareholders approve an increase to 200% of base salary as an absolute maximum. It applies to anyone who is in a position to have "a material impact on the institution's risk profile" – in effect, all senior managers and department heads – as well as anyone whose total annual remuneration exceeds €500,000 in one year, or who is otherwise in the highest-paid stratum of a bank's employees. It applies not only to all banks operating in the EU, whatever their parentage, but also to the international operations of EU-based banks. And in essence, its very existence illuminates a permanent philosophical gulf between "Europe" on one side and "Anglo-Saxon" financial capitalism on the other.

Representing the European consensus on this issue is EU commissioner for internal markets and services Michel Barnier – from the French centre-right UMP party – who saw the cap as a path "to discourage excessive risk-taking" in the aftermath of a financial crisis in which "some bankers took ever greater risks because they were being paid through an unlimited bonus pool . . . Enough is enough. We have to put a stop to that".

A rare British voice in support was Liberal Democrat MEP Sharon Bowles, one of the cap's instigators, who hailed the measure as "a much-needed culture change", while Labour shadow Chancellor Ed Balls focused on attacking Osborne for opposing it.

City bonuses are undoubtedly a hot potato in UK politics at a time when average wage growth across the rest of the economy has been below the rate of inflation for more than five years. But reaction to a Brussels-imposed cap was largely lukewarm or negative throughout the political establishment as well as the (broadly Eurosceptic) business community. The anti-cap side of the argument was also able to claim the support of Bank of England governor Mark Carney, who called the EU measure "crude", not least because it reduced the possibility of "clawback" – the process by which bonuses paid in shares or deferred cash can be reclaimed if long-term performance deteriorates as a result of risk decisions taken by the recipients. "We would rather see more deferral, more equity and this ability to take it back when those risks come to light," Carney told a House of Commons committee.

Despite these challenges from London, the cap has been in effect since January 1 2014. It forms part of a wider set of EU rules, Capital Requirements Directive IV, which implement the latest global standards (known as Basel III) for the levels of capital banks must adhere to in relation to the scale of their balance-sheet exposures. A similar cap limiting bonuses for retail fund managers is due to be implemented by 2016.

Set in legislative stone these restrictions may be, but the Johnsonian slogan "We're not going to let it happen" has been a rallying call for the City of London. The case against the cap continues to be made vigorously by lobby groups such as the British Bankers Association – which says "decisions about pay are a matter for shareholders and not politicians" – and TheCityUK, whose broader role is to promote UK financial and professional services around the world.

"This is a very emotive subject," says Nicky Edwards, TheCityUK's director of policy and public affairs, "but our concern is that the cap doesn't achieve what it intended and will in fact have a detrimental impact on EU economic interests by driving business out of the EU into other jurisdictions.

"It's supposed to benefit the consumer by making banks safer and more stable, but in fact it leads to higher fixed costs [in the form of higher base salaries] which makes banks less flexible and more vulnerable to market shocks. We're in favour of fair and transparent remuneration policies in the interest of all stakeholders, including consumers and shareholders, but this cap is a very blunt instrument."

Financiers who benefit personally from City pay practices are less willing to be quoted by name, for obvious reasons, but fiercer in their criticism. One bond market veteran calls the cap "brainless . . . We've all accepted the need for the kind of clawback mechanisms Mark Carney talks about, but from a City point of view this cap just means we have to offer higher base salaries to attract talent, with a smaller element of variable pay. Earnings in our sector are as volatile as ever, so that means we'll have to do a lot more hiring and firing – and that affects efficiency and destroys institutional memory, which is an important safeguard against excessive risk taking. It reduces long-term thinking, and it lowers morale."

"And it's another nail in the coffin for universal banks and large-scale investment banking operations in London, because it will not only push a lot of people to go and work elsewhere in the world but it will also drive good people out of the bigger firms into smaller, boutique businesses that are below the radar for the cap."

It is too early to say whether any of those predictions are coming true on a significant scale – and data on remuneration patterns remains inaccessible or anecdotal. Bank of America Merrill Lynch, for example, announced early in 2014 that it would increase salaries for front-

office staff in Europe by about a fifth this year. Elsewhere, attention has focused not so much on what bankers are being paid within the cap calculations, but on what they are being offered outside it in the form of "role-based allowances".

These additional payments, ostensibly neither salary nor bonus, are set at the beginning of the year and paid at regular intervals – but, unlike salary, they can be changed or removed if business conditions change, without affecting the recipients' employment rights. An early exponent of the device was HSBC, which revealed that it would pay an allowance (in shares) worth £32,000 a week to chief executive Stuart Gulliver on top of his £1.2m base salary. More than a hundred other senior HSBC executives were to receive share allowances, while a further 550 would receive extra payments in cash.

As one left-wing campaign group commented, "HSBC haven't so much circumvented rules on bonuses as driven a coach and horses through them." But the practice received tacit support from Andrew Bailey, the Bank of England's deputy governor for prudential regulation, who called it "the least worst alternative.

Role-based allowances are thought to have swiftly become common in the City, with Barclays, Lloyds, Standard Chartered, Goldman Sachs among the other big names reported to have adopted them.

Indeed, a survey of 44 banks operating in Europe, published in July by the Mercer consultancy, found 55% of them planning to use allowances to bypass the cap, while around 70% were also preparing to seek shareholder consent to pay the 200% maximum level of bonuses within it.

Royal Bank of Scotland, 81% owned by UK taxpayers through the Treasury offshoot UKFI – and still some distance from full recovery after its 2008 crash – is a notable exception among UK banks on the latter point, having been firmly told by UKFI that it would not receive shareholder approval to exceed the 100% bonus level. Some commentators have pointed out the unintended consequence of the cap in this instance; that the already weak RBS is further weakened by being limited to paying (before allowances) a third less for key executive posts than its competitors.

The EBA undertook a fact-finding exercise on the use of allowances with the backing of the EU Commissioner, who wrote to EBA chairman Andrea Barnier: "It is important to show a strong proactive stance on this important matter and address the claims made that the spirit — if not the letter — of EU law is being disregarded." Last week's EBA report, attempting to outlaw role-based allowances, is part of what Barnier called a "co-ordinated policy response". But in truth Europe's policymakers have been comprehensively outplayed on this issue.

The cap appears to be unenforceable because in practice it is easily circumvented; it has failed to win the intellectual support of experienced central bankers such as Carney; and in Europe's only truly global financial centre, London, it is derided by market practitioners as an ill-designed measure that would damage their businesses if it was comprehensively applied.

If it has achieved anything, it is to highlight an irreconcilable difference of opinion – between those in Europe who believe Anglo-Saxon bankers are incorrigibly greedy, selfish and irresponsible, and those in financial occupations in London and elsewhere, who believe Brussels is incorrigibly hostile to free markets and ignorant of how success is achieved in them.

As another senior trader put it: "We just want to be able to pay to attract talent, it's as simple as that. There's this myth that what we do is easy. But it isn't. You won't find a tougher, more competitive place in the world to do business. It's an environment where you've got to be bloody good to make money." In Johnson's phrase, the EU bonus cap is seen by the City as a "vengeful and self-defeating" intervention in the free market for financial talent.