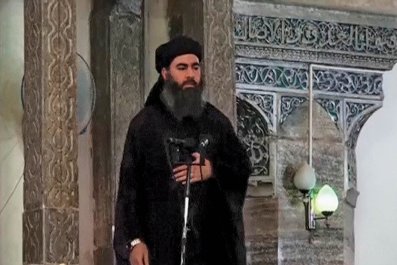

In the ongoing fight against the terrorists of the Islamic State (ISIS), Kurdish women have had the spotlight turned on them like never before. Since the siege of Kobane by ISIS fighters, images of gun-toting female Kurds have been splashed across the newspaper pages and TV screens of the West.

One, possibly mythological, female fighter has drawn particular attention. Dubbed the 'Angel of Kobani', she is beautiful and blonde-haired, is reputed to have killed a hundred ISIS fighters and has come to epitomise the media's portrayal of the Kurdish women involved in the war. Underneath the '"bad-ass babes" stereotype, however, the real stories of Kurdish women represent a much wider, though perhaps less glamorous, revolution – one in which they are seizing a new, leading role in society and attempting to shrug off the patriarchalism that pervades the region.

In Turkey, Kurdish nationalist parties have introduced a unique leadership model that goes well beyond the kind of quota systems imposed with varying degrees of success in parts of South Asia, but that often meet with derision, when proposed in Western countries. "Whenever there is an election now, there must be a male and female head of every organisation, whether it's a municipality, union, association or charity," explains Figen Aras of the Democratic Free Women's Movement (DOKH), an amalgamation of mostly Kurdish women's organisations and activists that is responsible for selecting female candidates for election. "It's a compulsory system, no one has the power to oppose this. Men don't have the chance to interfere in the decisions made here. We determine the candidates for parliament and for the co-mayoral system. But we also have an equal say in the selection of the male candidates too," she adds.

Since the municipal elections in March, all local authorities controlled by the Kurdish nationalists are headed by co-mayors: a man and a woman. However, because this system is not recognised by the Turkish government, it has thus far been implemented on a de facto basis. "We find the co-presidential system very effective at distributing power. It's not top down with one person telling everyone else what to do. In this case we have the initiative, we have a direct say in what the leaders decide," says Aras.

Necla Köroğlu of the Women's Academy, a school set up to train women in the region's capital, Diyarbakir, believes that the new system could have a great effect on the status of women in the region: "Having women in these positions is already paying off. We've seen women growing in confidence, feeling able to demand the things that they should be able to demand, and policies implemented to protect women's rights," she says.

The Kurdish movement has a long history of female involvement. Since the 1970s, women have made up a significant proportion of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) fighters and political involvement has been high.

"This is not something that has been handed to us. It is something that women have struggled for over many decades through political involvement," says Köroğlu. We managed to get a 30% quota, then a 40% quota, and now we have the balanced system we see today." However, the women are keen to stress that the task facing them is not simple. There is no doubt that Kurdish regions are still dominated by patriarchy, tribal traditions, and, particularly away from the cities, there are major hurdles to overcome. One of the key issues is the practice in some rural areas of marrying off child brides, explains student activist Dipak Ahmed. "After primary school, at the age of around 13 or 14 years old, girls are married off, often to much older men who will pay the girl's family large sums," Ahmed says. "This is a massive problem, and something that we are trying to fight. We are making people aware of the problem through extensive education programmes that go out into the regions. We also have programmes to get women involved in work so that there is less of a need for their family to take this kind of action."

For the child brides that do manage to flee their husbands, local municipalities have set up women's shelters that provide them with support and try to find them work. Indeed, one of the new co-mayors, Berivan Kilic, elected in Kocakoy in Diyarbakir province, was herself a child bride, helped out of an unhappy marriage by the staff of one of these centres.

It's not just in villages with traditional values that women face barriers. There are also cases of those within the nationalist movement attempting to block progress. "Of course there are instances where a woman is elected as a co-president or co-mayor, but is denied real power – is just a figurehead. This is something that has to be fought, and with the pressure the women's movement can exert, we don't believe that this is a major problem, and will be something that will drop away" says Aras.

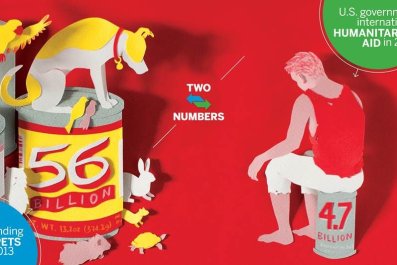

Female unemployment in Kurdistan is both the result of the policies of the Turkish state, including the clearance of 3,000 villages during the war in the 1990s, and a consequence of a traditional society that still sees women's place as in the home. To combat this, DOKH has set up cooperatives. These shops, farms and restaurants are run by women, with all profits shared by the workers. "This is about bringing women into working life and empowering them. But it is also about making an intervention into a market which is based on the maximum profit and which exploits women," says Aras. "In our cooperatives, everyone has an equal say in how they are run."

Ahmed says the fight is distinct from the more immediate struggle for freedom over how to dress or to move around at will: "That's fine, but this is not true freedom. The freedom we want is the freedom that real power brings."