John F. Kennedy was bored by civil rights. In the depths of the Cold War, his main concern—and passion—was countering the Russians. When, in the summer of 1963, the Freedom Riders were refusing to retreat from savage beatings at the hands of police in Birmingham, Alabama, the young president became annoyed. It was giving Moscow a free propaganda ride.

That's "exactly the kind of thing the Communists use to make the United States look bad around the world," he complained, according to his biographer Richard Reeves. The movement "was embarrassing him" on the eve of his Vienna showdown with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, making it appear that he couldn't control events in his own country. The president turned to his civil rights adviser, Harris Wofford, and complained about the Freedom Riders. "Stop them!" he demanded. "Get your friends off those buses." On another occasion, when Maryland's Jim Crow laws prevented African diplomats from eating in white-only diners as they drove from New York to Washington, Kennedy gibed, "Tell them to fly."

"Race was having a devastating impact on U.S. foreign relations vis-à-vis the Russians," recalls Mary Dudziak, a fellow at Stanford and author of Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy. American diplomats struggled to make the case for peaceful, democratic change in the Third World (especially when the local dictator was a U.S. ally). The question was, "How can you appeal to people in newly independent countries when they see pictures of police dogs attacking protesters [in Birmingham]?" she said. "The racial problems in the U.S. undermined our ability to criticize" friendly regimes who were repressing their minorities.

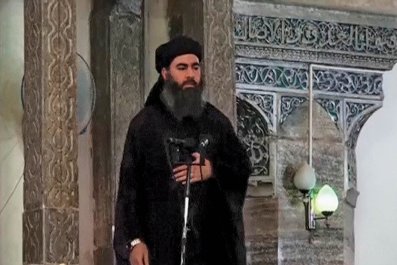

President Barack Obama faces a similar challenge with the rush of bad news, photos and videotape from Ferguson, Missouri, New York's Staten Island and elsewhere, Dudziak says. More than 50 years after Birmingham, America's race problems are again front-page news, from London to Baghdad, Beijing to Tehran—and of course trumpeted to the remotest mountaintops via Arab-language radio and television stations. Russia, China and ISIS are all crowing about American "hypocrisy" in social media.

If Obama hopes to turn this around, she says, he needs to take a page from JFK. "As the crisis in Birmingham played out," Dudziak recounted in Foreign Affairs in August, "many looked to...Kennedy for action. As civil rights adviser Burke Marshall would later put it, Americans were left wondering, 'Why didn't he do something?' Ultimately, the president did do something. Namely, he sent Marshall to Birmingham, where he met with leaders from the civil rights movement and local government and businesses, and they worked out a compromise plan to desegregate the city and release jailed demonstrators. But by then Birmingham was more than a local crisis—it was also a national and international one. Because of that, managing it required more."

Kennedy did do more, after Alabama Governor George Wallace dramatically stood in "the schoolhouse door" at the state university to block the enrollment of African-Americans. Taking steps that would eventually turn out to be political suicide for the Democratic Party in the South, Kennedy federalized the National Guard to protect the black students, drew up a major civil rights bill and, in a major address at American University, called civil rights "a moral issue…as old as the Scriptures and…as clear as the American Constitution." He said, "The heart of the question was whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated."

But his most pointed remarks were shaped to make integration as much a foreign policy imperative as a moral one. "We preach freedom around the world, and we mean it, and we cherish our freedom here at home," he said. "But are we to say to the world, and much more importantly, to each other, that this is a land of the free except for the Negroes; that we have no second-class citizens except Negroes; that we have no class or cast system, no ghettos, no master race except with respect to Negroes?"

The reaction to the speech was electric in corners of the world where the U.S. and USSR were vying for the hearts and minds of millions mired in hunger, disease and hopelessness. The American ambassador to strategically prized Ethiopia cabled home that, "the tone of the press immediately improved," according to Dudziak's research. "Emperor Haile Selassie thought the statements were 'masterpieces.'" Similar responses came from elsewhere, but there was also caution: "Actions will speak louder than 'torrents of words,'" the American Embassy in Senegal warned.

And so it is today. To "change the narrative" abroad, Obama needs to do more than sic the feds on local police departments and prosecutors to make sure they followed proper procedures in race-tinged cases, argues Dudziak, who is also director of Emory University's Project on War and Security in Law, Culture and Society. "Obama needs to present [racial discrimination] as one of the nation's most pressing and urgent problems." And act. Find a way to rid local authorities of bad cops and weak prosecutors.

The alternative, Dudziak says, is ceding the battleground to the very dark forces now closing in on Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria. "In the early 1960s what was at stake was nuclear war. There was fear that the U.S. and the Soviets would go to war with each other and blow up the world," which they nearly did over Cuba in 1962. "Now, the U.S. has consolidated its power, but the U.S. still wants and needs" a powerful, positive message to compete for young minds tempted by the siren song of Islamic revolutionaries. "We can't pursue a human rights agenda abroad if we're not protecting them at home," she said.

And only Obama has the power to lead in this arena. "Sometimes leadership matters and inspiration matters," Dudziak says, harking back to JFK's stand against racism. Obama, she says, needs to rediscover the rhetorical skills, not to mention the audacity, that he displayed so amply as a candidate in 2008, and apply them to the current crisis.

"He's had the gifts of that in the past," she said. "I wish we were hearing a more powerful voice from him on this issue."

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled Emory University, and misstated Ms. Dudziak's affiliation with Stanford. She is a fellow, not professor.