A man and a woman are screaming at each other in Arabic, rehearsing a scene from We Are All Refugees, a six-part radio soap about the lives of Syrian refugees in Jordan, due to be broadcast throughout the Middle East this month. The project reflects life in a country where three-quarters of the population are now estimated to be refugees, and to which over half a million Syrians have fled in three years.

The actors doing the shouting in a rehearsal room in Amman are Nawar Bulbul, a Syrian TV matinee idol; 26-year-old Azmi al-Hassany, a young Syrian amateur actor; and Raneem Ibraheem Aga, 23, a Syrian refugee. Bulbul's character, Fadi, is trying to marry off his 15-year-old sister, Reem (played by Aga), to a young Jordanian suitor against her will, to get her out of the refugee camp and off his hands. Fadi's younger brother, Firas, the drama's hero (played by al-Hassany), has returned to the camp from Amman to support his sister. He is scraping out a living working illegally as a valet parker in the capital.

"This story is happening every day with Syrians in Jordan, they just don't have much choice," said Aga during a break in rehearsal. "But Reem is strong. She comes up with a way to help her family solve the problem. I hate the idea of a young girl being forced to marry. I was 17 when I did, but I loved my husband."

Aga fled a bombardment in Damascus two years ago with her husband and two sons, ages 3 and 5, to find a new life in Syria. A delivery driver in Syria, her husband now hustles for work on the Jordanian black market as a metal worker. He did not want Aga to act in the soap. "But I nagged and nagged and nagged him until he said yes! I'd always wanted to act, but I never had the chance. And it's paid," she said, smiling, before being summoned back to work.

Our Jordanian driver, Ossama—gripped by the scene—said the plotline was compelling and truthful: Syrian women are thought to be beautiful, clever and great cooks. "There's a saying in Jordan: 'Marry a Syrian wife; have a good life,'" he says, a little sheepishly.

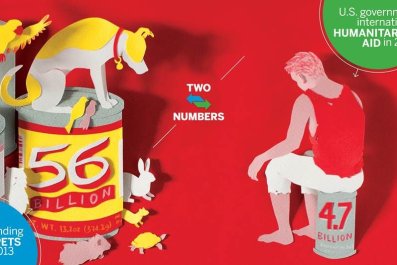

The idea for the soap, of which I am a co-producer, was born a year ago, when Oxfam took me to Zaatari, the U.N.'s tent and Portakabin city where more than 100,000 of Jordan's half-million Syrian refugees are corralled. Unfortunately, Jordan, a tiny, desert country of 8 million people, with no oil, not much water and 12.6 percent unemployment, was already feeling the strain of being the most politically stable country in the Middle East and therefore a magnet for exiles.

The Syrians are just the latest wave of refugees. The Palestinians came in 1948 and again in 1967; Iraqis in 1991, 2003 and again this summer, as they fled the medieval barbarism of ISIS. There are even Armenians, well established now, who filtered down through the wreck of the Ottoman Empire after the genocide against them in 1915.

At the time, I was visiting the camps looking for a place to stage The Trojan Women, Euripides's great antiwar tragedy, as a drama therapy project for refugees. Syrian women talked in the tents and white corrugated plastic boxes they now called home. One girl was about to be married; she was just 15. Her mother, a country woman from a village near the Syrian town of Deraa, explained that marriage was the best solution for her daughter. "There's so much gossip here," she said. "No one has anything to do in the camp; we all know each other's business. People say terrible things about unmarried girls. They call them flirts or sluts."

"And there's no security in the camps," said another woman. "Some girls get attacked or molested when they are going to the bathrooms at night, and then no one will marry them."

"I just want my daughter to be safe," said the first woman. After her mother left, the girl burst into tears, saying, "I don't want to get married. I don't want to leave my family." She was to marry a Jordanian and move out of the camp. "A Jordanian husband will look after her; her children will have Jordanian citizenship," her mother later explained to me, desperately.

We Are All Refugees was partly funded by the United Nations high commissioner for refugees (UNHCR) agency, which suggested the themes it wanted covered. Forced early marriage was one, since there's been an epidemic of arranged marriages for Syrian refugee girls—to other Syrians, to Jordanians, even to Saudis and Gulf Arabs, who come to the camps to find a bride. Other themes were domestic violence, water shortages, unemployment, the exploitation of young Syrians who are not allowed to work legally in Jordan and the tensions of two communities forced to live side by side.

The drama was co-written by Wael Qadour, a young refugee Syrian playwright and theater director, and two Jordanians, Majd Hijjawi, a writer and filmmaker, who also worked on The Hurt Locker, and Ahmad Ameen, who wrote the award-winning film Transit Cities.

Originally, it was to be a TV soap. But radio is much cheaper to produce, and most of the money had to be raised privately. One inspiration was Britain's The Archers, the world's longest-running radio soap, broadcast on Radio 4 and a daily addiction for 5 million listeners. It was created in 1951 with an educational purpose: teaching new farming techniques.

There were other models. In 1994, the BBC World Service had enormous success with its Afghan soap Naway Kor, Naway Jan (New Home, New Life). Dealing with the problems of Afghans returning from the refugee camps in Pakistan to a then-peaceful Afghanistan, its message was "Don't tread on the land mines, or grow opium, however much the drug lords pay." It now has more than 35 million listeners and has been running for 20 years. The Taliban tried to take the soap off the air, but the ban was blocked by a mutiny by its own troops.

We Are All Refugees, set partly in a camp and partly in Amman, is to be broadcast on Radio Souriali, the best-known Syrian independent émigré radio station, which broadcasts in the Middle East (including Syria and Jordan), the U.S. and online, and also on the UNHCR website.

In the soap, Yara, a naive, middle-class Jordanian heroine who works for a nongovernmental organization, is played by Shereen Zoumot, a Jordanian-Iraqi actress and producer. Zoumot's mother's family fled Mosul, Iraq, for the relative safety of Baghdad, where her uncle was wounded in a car bomb last month. "Yara's exactly like I used to be," said Zoumot, 26, who acted in When I Saw You, the Palestinian entry for the best foreign language film Oscar in 2013. "She's an airhead for the first three episodes, then she gets real. I know she'll get together with Firas in the end. Loads of Jordanian girls are going out with Syrian guys now."

The long-term ambition is to turn the radio pilot into a TV soap. "Although my husband might actually divorce me if it goes on TV," said Aga, laughing.

Charlotte Eagar is a filmmaker and a contributing editor at Newsweek Europe. Last year she co-produced Euripides's Trojan Women in Arabic in Jordan, and she is a co-producer for We Are All Refugees.