The Newsweek staff reads a lot.

This I learned on my first day of work, with a simple glance around the office's interior. I was—and remain—seated next to senior writer Victoria Bekiempis, whose desk looks like a cubicle-sized library as organized by a black bear. Further down the aisle sits senior writer Alexander Nazaryan, though you can't really see him unless you peer over, or around, the Pisa-style stacks of books that threaten to topple onto him daily. Sometimes those stacks of books spill over into neighboring cubicles, and sometimes they multiply and wind up in bedrooms and waiting rooms and on the L Train and—yes—on this very website and in the magazine.

Though far from exhaustive (our apologies, Monsieur Piketty), this 20-book list is meant as a small glimpse at the books we read and loved in 2014. It's an eclectic grouping, ranging from scholarly tomes about tax policy to National Book Award winner Phil Klay's war vignettes to blog-to-book offerings from The Toast's Mallory Ortberg and Pitchfork Reviews Reviews' David Shapiro.

Anyway: Happy reading, and do support your local independent bookseller. —Zach Schonfeld

BAD FEMINIST by Roxane Gay (Harper Perennial)

Culture critic Roxane Gay writes about reality television, teaching, terrible teen novels and contending with the conflicting values that make her a "bad feminist" in this touching and crucial essay collection. The works are compiled essays Gay has published elsewhere, from The Rumpus to Salon, but whose common thread is grappling with the political and personal complications that come with seeking social justice. Gay's true gift is the ability to pen lean prose, though: She explains complex, nuanced terms in a bare-bones way, and tells relatable stories that make us, at heart, all bad feminists. If you're interested in critical thinking about culture, this book is a must. —Paula Mejia

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SEVEN KILLINGS by Marlon James (Riverhead)

"Every time you reach the edge, the edge move ahead of you like a shadow until the whole world is a ghetto, and you wait."

That's Bam-Bam, at 14 years old, a future member of the infamous Shower Posse gang, talking about growing up poor in a Jamaican shanty—and also capturing the main theme and thrust of Marlon James's novel A Brief History of Seven Killings. Bam-Bam is one of over a dozen characters whose voices James renders into discrete units that range from Bam-Bam's rough Jamaican patois to the spook-speak American English of CIA pencil-pushers to the controlled colonial English of a dead (yes, speaking from beyond the grave) Jamaican Brit. Together, they create a cacophony used to tell the wide-ranging story of Jamaica, the place and idea. It's a sweeping novel that touches on family, friendship, celebrity, art, sexuality, ghetto politics, geopolitics, drug trade, gender, race and more, sending the reader from Jamaica to New York via Miami and Cuba and back. But at its center is conspiracy, the shifting realities that Bam-Bam alludes to when he talks about mercurial edges.

Did you know that there was a politically motivated assassination attempt on the life of Bob Marley in 1976, days before the huge "Smile Jamaica" peace concert? That the CIA may or may not have taken a keen interest in the rise of Jamaica's socialist-leaning government and the growing Cuban influence in the country at the time? That the CIA may have been integral in arming and training the Shower Posse, which still operates throughout the world, primarily in the New York metro area? That many believe that the early death of The Singer (as Bob Marley is called in the book) was, ultimately, the CIA's doing?

A Brief History of Seven Killings will send you down this path. The question, at the end, is whether this book is dangerous—is there a classified file that now contains a redacted copy of the text?—or is it just-for-fun, a parody of parodies where brutal killer Josey Wales (a leading member of the Shower Posse) is just a silly man a bit too into American Westerns? —Elijah Wolfson

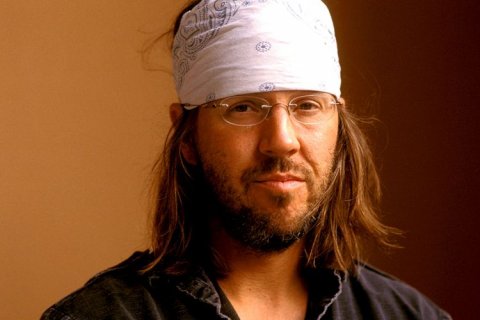

THE DAVID FOSTER WALLACE READER by David Foster Wallace (Little, Brown and Company)

A collection of both fiction and nonfiction by the bandana-wearing polymath, who was unusually adept at continental philosophy, tennis, cultural criticism and, well, old-fashioned storytelling. This selection includes chunks of his three novels, as well as some of his famous essays: on lobsters, on irony, on why Kafka was funny. Did you know, by the way, that Kafka was funny? Wallace explains why. —Alexander Nazaryan

IN PARADISE, by Peter Matthiessen (Riverhead)

If Peter Matthiessen had been a character in one of his own novels he might have been bounced for straining credibility. Scion of a Boston Brahmin family (his father's cousin F.O. Matthiessen changed our consideration of 19th century American literature); adventurer (he went to New Guinea in 1961 with Michael Rockefeller, who was later eaten by cannibals); award-winning travel writer and memoirist (The Snow Leopard is a classic in both genres); celebrated novelist (Killing Mister Watson, At Play In the Fields of the Lord); CIA operative (The Paris Review, which he co-founded, was started with money from the agency), Matthiessen, who died shortly after the publication of his last novel, In Paradise, exploded boundaries.

In Paradise draws on a different facet of the author's experience. As a Zen master (yep) he traveled on "Bearing Witness" retreats to former Nazi concentration camps, though Clements Olin, his fictional counterpart, is imbued with a healthy skepticism about the process: "Dear God," he thinks to himself, "in the echo of such desolation, what more witness could be needed?" In the course of his week at a Polish charnel house he encounters clownish American hippies, one angry German and even develops a crush on a nun. Olin speaks to her of the Christian myth of the penitent thief, crucified with Jesus, who asked to be taken to heaven with Him.

"In traditional gospels Jesus responds, 'Thou shalt be with me this day in Paradise,' but in older texts—Eastern Orthodox or the Apocrypha, perhaps?—Christ shakes His head in pity, saying, 'No, friend, we are in Paradise right now.'"

Zen bones, daddy. —Sean Elder

IT WILL END WITH US by Sam Savage (Coffee House Press)

I wasn't planning on readingIt Will End With Us by Sam Savage. I just happened to pick it up from the office book table here, and after flipping through a few pages, I was glad I did. It is a meditative short novel about Eve, an older woman who is somewhat reluctantly writing down her memories. It tells the story of her growing up in the South in the 20th century. It is composed in a pointillist style, of one-sentence paragraphs. Each is like a frame of movie film, accessible alone, but changed by context of neighboring sentences. There is no cause and effect. In fact, the paragraphs often read, at first, like non sequiturs.

Eve writes about her family, relationship with her mother (with whom she was close), her father (with whom she was not) and her siblings, all of whom have apparently died (one unaccounted for and presumed dead) and all were childless. The overall effect is of one dispassionately reviewing their life. In its style, the novel evokes Donald Barthelme's Snow White or Faulkner's As I Lay Dying, though it is much more accessible than either. —Joe Westerfield

THE LAUGHING MONSTERS by Denis Johnson (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Early in The Laughing Monsters, Denis Johnson's tale of misadventure and espionage in central Africa, the narrator, a NATO spy named Roland Nair, addresses his handlers about his assignment to spy on his erstwhile friend, an African soldier of fortune named Michael Adriko. "And while you, my superiors, may think I've come to join him in Africa because you've dispatched me here, you're mistaken. I've come back because I love the mess. Anarchy. Madness. Things falling apart. Michael only makes my excuse for returning."

Over 10 novels Johnson has dabbled in a number of genres: Western (Train Dreams), pulp (Nobody Move), gothic (Already Dead). In Laughing Monsters he steps onto the post-colonial espionage turf of Robert Stone and Graham Greene (the title sounds like an homage to Greene's Haitian novel, The Comedians, but is actually the name of two Congolese mountains) and what turf it is: Everyone we meet is half-mad with some unnamable passion for plunder of one kind or another. And though there is plenty of suspense (their kidnapping by a rebel army is particularly harrowing), Johnson, as always, is devoid of cliché. Here is Nair meeting Adriko's fiancée, an African-American woman named Davidia: "She laid two fingers on my wrist and seemed to watch my face as if to gauge the effect of her touch, which stirred me, in fact, like an anthem."

A romantic triangle ensues, though how reciprocal Davidia's feelings are is uncertain. Uncertainty is the lot of Johnson's characters; Adriko—back to burn some rebels, or Mossad, or the U.S. with some scam—forever says, "More will be revealed." That's an AA slogan, but there is precious little sobriety here. "I was drinking more than ever in my life," says Nair. "I couldn't relax or feel like myself in this region without banging myself on the head with something."

Adriko is the magnet that holds the narrative together. A native Ugandan, trained by the U.S. Special Forces, he is a walking contradiction, attracting "orphans and magicians and circus people," as Nair says. At one point beside a broken down bus a shaman speaks to them as Adriko translates. "He says we are all captives in this world," he tells them. "We were stolen while we were asleep and we were carried here, and now we're held captive in this world of dreams, where we believe we're awake." —Sean Elder

LOST AND FOUND IN JOHANNESBURG by Mark Gevisser (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

South African author Mark Gevisser is a lover of detail—one of his previous books, a 2007 biography of Nelson Mandela's successor as president of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, clocked in at almost 900 pages—so it's no wonder the author was obsessed with maps as a child.

In Lost and Found, Gevisser takes the reader on a number of journeys, starting with his childhood love of the markings and mysteries of an old, battered book of road maps. He describes his exploration of Johannesburg, South Africa's largest city, its racial division and his discovery of his own sexual identity. He tracks the journey of his own family of immigrant Jews to South Africa from Ireland, Lithuania and Israel. And he describes in lyrical detail the brutal impact, and eventual demise of, apartheid, South Africa's entrenched policy of racial segregation.

Throughout, the old road maps force the author "to remember something I must never allow myself to forget: Johannesburg, my hometown, is not the city I think I know." The book returns to a single moment several times: a violent home robbery that brought Gevisser face-to-face with the brutal contradictions of his beloved city.

Gevisser's memoir is replete with local references and South Africanisms that might be lost on some readers, but the story is universal: that of a person struggling to find his place in a city that has both nurtured him and ripped him apart. —Jackie Bischof

LOST FOR WORDS by Edward St. Aubyn (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Bad writing is at the foundation of Edward St. Aubyn's seventh novel,Lost for Words. Not his: Best known for the Patrick Melrose novels, which skewered a certain segment of the British upper class with the wit of Waugh and the grace of Woolf, St. Aubyn spews out jewel-like sentences like a South African diamond mine—and given the subtext of child abuse and drug addiction in those books, there is nearly as much pain involved.

Lost for Words is a departure in tone and topic. Lampooning the judging process behind the Man Booker Prize, the annual British literary award that gets the sort of attention there the Oscars do in the U.S., St. Aubyn knocks down a number of stereotyped lit twits (a French deconstructionist peddling a book called Qu'est-ce la Banalite?; an actor-judge who doesn't have time to actually read the entries) but saves his best stuff for the book parodies themselves.

"Oh happy horse that bears the weight of Essex!" William Shakespeare exclaims in a novel about his life, while one of the favored candidates is a working-class Scottish novel called wot u starin at ("Death Boy's troosers were round his ankies"). British critics assumed St. Aubyn was having his revenge on the Booker (which passed over two of his Melrose novels), if so, the revenge is pretty sweet. One of the judges, a former Foreign Office worker who now writes bad espionage books, uses a cliché finder called Gold Ghost Plus: "When you typed in the word 'refugee' for instance, several useful suggestions popped up: 'clutching a pathetic bundle,' or 'eyes big with hunger...'"

Fitting that this book won this year's Wodehouse Prize. Carry on, St. Aubyn. —Sean Elder

MARRIAGE MARKETS: HOW INEQUALITY IS REMAKING THE AMERICAN FAMILY by June Carbone and Naomi Cahn (Oxford University Press)

The popular belief that marriage makes for stronger family economics has it backward, June Carbone and Naomi Cahn argue. Reliable and plentiful jobs make for strong families with good incomes, not the other way around. Marriage is evolving, becoming more durable among the better educated while declining among those with less income and schooling, argue the authors, law professors who specialize in family economics. Their previous book, Red Families v. Blue Families, showed that divorce is more common in Bible Belt states than less religious liberal strongholds.

Black women and working class women of all races increasingly believe in their own ability to earn an income and raise children on their own. Marriages between economic equals who are emotionally mature and who delay childbearing produce the best matches, they show. In easy-to-read prose, the authors also show how divorce courts erect barriers between poor dads and their children, while expanding the rights of rich dads. Changing attitudes about marriage require overhauling family law to both strengthen unions while ending the presumption that marriage is best for rearing children. —David Cay Johnston

THE NAZIS NEXT DOOR: HOW AMERICA BECAME A SAFE HAVEN FOR HITLER'S MEN by Eric Lichtblau (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

The Nazis Next Door is not for those who prefer to stick to a "good guys, bad guys" storytime narrative of World War II and its aftermath. But for those who are willing to look beyond the heroic image of American troops liberating death camps and saving Europe to a more nuanced history of the war's end and the fate of the Nazis in subsequent decades, Eric Lichtblau has written a captivating account.

Lichtblau—an investigative reporter in Washington for The New York Times who won a Pulitzer Prize in national reporting along with James Risen in 2006 for their work on the NSA's secret domestic wiretapping—follows former Nazis and Nazi collaborators who lied their way into the U.S. or were knowingly recruited and protected by the CIA, FBI, and other agencies to work as spies and scientists. The percolating Cold War presented a new enemy, the Soviet Union, and the Nazis were all but embraced as tools to thwart Communism. Many lived comfortably in the U.S. for decades and efforts to prosecute them were met with government roadblocks and public indifference. The events Lichtblau recounts is infuriating, flipping American textbook history on its head, but that makes it all the more an important read.

The Nazis Next Door reads with the ease of fiction even as the author draws on a litany of declassified documents, extensive interviews and other sources. I had a chance to speak with Lichtblau about the book soon after it was published in October. —Stav Ziv

REDEPLOYMENT by Phil Klay (Penguin Press HC)

This collection of short stories about war opens with a bunker buster: "We shot dogs. Not by accident." Like the soldiers depicted therein, these stories are muscular and laconic, yet brimming with subtle wisdoms. "OIF," told almost entirely in military jargon, ambushes you with feeling. Klay, who last month won the National Book Award, said as he claimed the prize that "war is too strange to be processed alone." He has written a book to make us all understand. —Alexander Nazaryan

SEASON OF SATURDAYS: A HISTORY OF COLLEGE FOOTBALL IN 14 GAMES by Michael Weinreb (Scribner)

Two of the better modifiers for both college football and its fans are passionate and parochial. Author Michael Weinreb, a State College, Pennsylvania, native, weaned on Penn State football, is both. But Weinreb's tome extends far beyond Happy Valley, as he plumbs 14 games in the sport's history—beginning with the first, in 1869—to trace both college football's evolution as well as its cultural impact. Weinreb also unapologetically plots the arc of his own fandom which, for a sportswriter who was raised on the altar of Joe Paterno, makes for intriguing introspection. Season of Saturdays is a must-read for any acolyte of Saturday football. —John Walters

SHOVEL READY by Adam Sternbergh (Crown)

If you spotted me shivering on the subway in bleakest January, a terrified glare on my face and book in my hand, I was probably reading (or "taking in" seems the better verb) Shovel Ready. A dystopian neo-noir novel by Vulture and New York Times Magazine contributing editor Adam Sternbergh, Shovel Ready is not about the dirty bomb that hollows out Manhattan some 15 or 20 years into the future. It's about what comes after: hitmen, televangelists, feed bags and devastation that plays out both virtually and IRL. Chronicled from a killer-for-hire's perspective, in prose sharp and grim enough to bring the term hardboiled back into critical parlance, it's a nightmarish book that's tough to read but tougher to quit reading halfway through. —Zach Schonfeld

THE TEACHER WARS: A HISTORY OF AMERICA'S MOST EMBATTLED PROFESSION, by Dana Goldstein (Doubleday)

Most everyone has an opinion about public education; far fewer really have the pesky facts about what our kids know, what our teachers actually make, why the schools in Massachusetts rock and the ones in Mississippi suck. Goldstein is in the latter category and here delivers a cool-headed history of the teaching profession, which has lately become roughly as politicized as Middle Eastern politics and abortion. The truth, as Goldstein capably shows, is always a little more complex. Both the Koch Brothers and Rachel Maddow could learn something from this book. So could the rest of us. —Alexander Nazaryan

TEXTS FROM JANE EYRE by Mallory Ortberg (Henry Holt and Co.)

Texts from Jane Eyre by The Toast editor Mallory Ortberg is a better book than Jane Eyre, probably. I say probably because I've never read Jane Eyre. There are two big reasons for that: 1) Jane Eyre is really long, and; 2) Jane Eyre doesn't have any space marines, dragons, trolls, magic swords, or anything like that. Jane Eyre is just about some woman who is sad because living in Victorian England or whatever sucks. No duh. To be fair, Texts from Jane Eyre doesn't have any cool space action or dragon-slaying, either, but it has other redeeming qualities. For one, it's not just about texts from Jane Eyre. There are texts from other literary personages, such as: Achilles; Hamlet; Cormac McCarthy (I especially like the texts from Cormac McCarthy. I bet he doesn't even know how to text).

Mallory Ortberg is funny. She thought, What if some fancy book people talked just like us normals? Wouldn't that be hilar?

It would. It is. Good job, Mallory. —Taylor Wofford

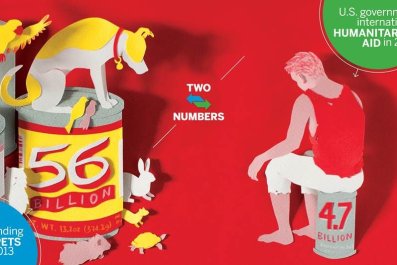

WE ARE BETTER THAN THIS: HOW GOVERNMENT SHOULD SPEND OUR MONEY by Edward D. Kleinbard (Oxford University Press)

Americans feel the pain of an income tax system that raises twice as much as it actually does because of hidden spending through tax favors. This masterpiece on how we tax ourselves, and how Congress spends our money, explains why the mostly lightly taxed modern country feels so heavily burdened while offering workable solutions.

Drawing on insights from Adam Smith's The Theory of Moral Sentiments, lawyer Edward D. Kleinbard shows how applying ancient financial and moral principles would make America happier, healthier and wealthier. Kleinbard spent two decades designing sophisticated tax avoidance strategies for rich clients before becoming a law school professor on a mission to expose the tax system's flaws.

Kleinbard says liberals err in focusing on raising tax rates at the top, while conservative "market triumphalists" ignore how social safety nets and social insurance encourage optimal levels of investment and risk-taking by strivers. His antidotes include a consumption tax to finance public benefits like education, health care and infrastructure, as the Nordic countries do. He also proposes simple ways to lower taxes on business stopping big companies from profiting off their taxes by deferring tax payments for years or decades. —David Cay Johnston

WHAT IF?: SERIOUS SCIENTIFIC ANSWERS TO ABSURD HYPOTHETICAL QUESTIONS by Randall Munroe (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

The Internet is history's greatest repository of minutiae, and its greatest generator. And that information is proliferating, with a locust like storm of knowledge-providers that don't bother checking for veracity and rarely, if ever, provide a modicum of insight.

This is the world inhabited by the stick figures of 29-year-old former NASA roboticist Randall Munroe's popular webcomic XKCD, who are by turns exasperated, fascinated, ironic and sardonic—humans trying both to understand, and dig themselves out of, the informational mess we've made. They have a decidedly different relationship to the absurd cascades of information than do the supposed "curators" of information who guilefully sell wonder while retaining none of it themselves.

His latest book, What If? Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions, is a slightly different approach to the same problem. Instead of providing inane, useless and often incorrect answers to unasked questions, Munroe takes inane, useless and often quite pointless questions asked by real humans (mostly sent to him through his website), and turns them into beautiful expositions on the impossible that illuminate the furthest reaches, almost to the limits, of the modern sciences. The first chapter, "Q. What would happen if the Earth and all terrestrial objects suddenly stopped spinning, but the atmosphere retained its velocity?" ends with the anthropomorphized moon worrying over the state of the Earth, and, with the gravity generated by its own rotation around the Earth, saving our dying planet. The physics are real; so is the emotional content. —Elijah Wolfson

THE WILD TRUTH by Carine McCandless (HarperOne)

It's an odd feeling when you've known—or thought you've known—a story for years and find yourself confronted with the reverse perspective you've never thought to consider. That's what powersThe Wild Truth, the new memoir by Carine McCandless, whose brother Chris McCandless posthumously found fame as the self-styled Alaskan explorer who abandoned a comfortable upbringing to journey west and trek into the wilderness.

The elder McCandless perished in 1992, but his sister fills in holes where Into the Wild author Jon Krakauer could not, specifically centering on the family history of abuse and deception that drove her brother to sever ties in the first place. It has been a long time coming: "I felt like I was doing a disservice not just to Chris and his memory but a disservice to all of the people who seek inspiration from [him]," McCandless recently told me in an interview. The Wild Truth is a moving narrative of domestic abuse, grief and survival, and for the perspective and revelations it contains, an essential addition to the Into the Wild story. —Zach Schonfeld

YES PLEASE by Amy Poehler (Dey Street Books)

The Parks and Recreation star makes her writing debut, and it's delightful. Yes Please is less a book and more a compendium, in which a memoir, advice column, essay collection, faded photograph and ripped diary pages intersect. Poehler is frank and funny throughout the book, as is her nature, but her writing unearths a wise narrator who's seen some of the worst of life and come out the other side unscathed. She discusses her come-up from her humble Boston area hometown to scraping by in New York, to motherhood to the moment when things started to cement—but assures us that she still doesn't totally have it together, and that it's OK. Can we get more from Amy Poehler? Yes, seriously, please. —Paula Mejia

YOU'RE NOT MUCH USE TO ANYONE by David Shapiro (Little A/New Harvest)

Glance briefly at the jacket praise decorating the hardcover edition of David Shapiro's debut novel, You're Not Much Use to Anyone: Shapiro is "the obsessive voice of a generation that can see every little crazy thing—except themselves—more clearly than ever," raves Awl co-founder Choire Sicha. His book is "the Bright Lights, Big City of the click-here-now generation," echoes A Sense of Direction author Gideon Lewis-Kraus. Shapiro, ostensibly, is the voice of his generation—odd praise for a first-time novelist who openly admits this book is "all I got."

But that fleeting relevance aligns eerily well with the blink-and-it's-gone quality of Internet fame, an ephemeral high that's really at the center of David Shapiro's transparently autobiographical love story. Written by an anxious NYU grad named David who found unexpected literary success writing a Tumblr blog called "Pitchfork Reviews Reviews," the novel chronicles the personal and professional yearnings of an anxious NYU grad named David who finds unexpected literary success writing a Tumblr blog called "Pitchfork Reviews Reviews." So yes, it's a "novel" that shares the sometimes discomforting self-scrutiny of memoir and the wordy, awkward charm that won Shapiro's blog some 30,000 Tumblr followers and a 2010 New York Times profile in the first place. The result is a smartly meta meditation on attention, self-worth and social status in the age of the blogger: an unknown Shapiro envisions his Pitchfork.com (then "PitchforkMedia") writer-nemeses, tall men "drinking Hoegaardens on the rooftops of their Brooklyn luxury condos," and suddenly he has seized a small glimmer of that fame to find it only brings confusion, and what then?

The answer, perhaps, lies outside the boundaries of this seemingly cathartic text: enroll in law school and concede you have nothing more to say. —Zach Schonfeld