Like many grieving parents, Herbert and Edith May Brownscombe treasured every memory of their son Brian. They had made sacrifices to send him to private school and were proud when he grew up to be a doctor. When he was killed in 1944 during the Battle of Arnhem, they, like the families of the other 1,400 or so victims of this bloody episode of the Second World War, mourned their loss. But this personal tragedy was different. Brian, an army doctor and prisoner of war, was shot in cold blood by a Nazi officer. His killer, Waffen-SS Officer Karl-Gustav Lerche, who spent years on the run under a series of assumed identities, was eventually caught and served five years for the crime.

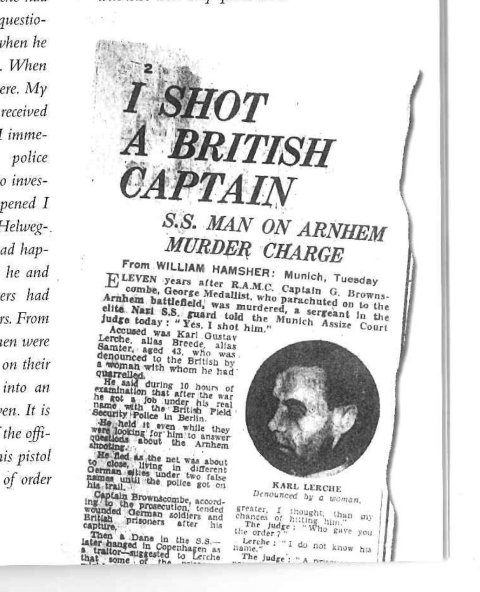

But for the actions of his former lover, Lerche would never have been brought to justice. He had been doing odd jobs in Munich and had taken up with a woman called Charlotte Bormann. In September 1952 she walked into her local police station to denounce the man she had come to despise. Tired of his lies, Bormann told police that the man she knew as Gunther Breede was both a fraud and killer. In reality he was named Karl-Gustav Lerche who had admitted to killing a British POW in the war. Bormann, too, had form, although not of the criminal kind. The 54-year-old had married and divorced three husbands. Notably one of them was the nephew of Nazi leader Martin Bormann.

Eight long years after his death, the Brownscombe murder was about to be solved. Brownscombe's nephew, George Pitcher, grew up with a sense of a gaping hole left by his death. "At my grandparents' house, Brian was memorialised with great affection," recalls Pitcher, a journalist and priest. "They had his school blazer badge, with his George Medal hanging from it on the wall. But what set us apart from other families of dead soldiers was that Uncle Brian hadn't died in combat. There was this unresolved issue."

Drinking With the Enemy

The issue wasn't just that the dashing Captain Brownscombe, known as 'Basher', had been shot off the battlefield; it was that he'd been shot after an evening of merry drinking with his captors. It had been an unusual gathering. Shortly after landing near Arnhem in September 1944, as part of an audacious Allied plan to reach Germany's Ruhr area through the Netherlands, 28-year-old army doctor Brownscombe had been captured by German forces. He had plenty of company: during the Battle of Arnhem, which raged from 17 to 25 September, 6,000 of the 10,000 allied soldiers deployed in the immense operation were captured, while 1,400 were killed.

The battle also having resulted in vast numbers of British and German wounded soldiers, Brownscombe and the two other captured British doctors were assigned to duty at the German army hospital. In fact, the collaboration was a minor success, with the doctors going about their work in the spirit of Hippocrates. Watching this friendly co-existence, a Waffen-SS officer also stationed in Arnhem decided that it would be good to socialise with the British POWs.

Waffen-SS Unterscharführer Knud Fleming Helweg-Larsen was a decidedly colourful character: a Dane born to a pastor serving in the Danish West Indies, who had worked as a cowboy in South America (and written a book about it) and admired Ernest Hemingway. Having left South America for Copenhagen in the late 1930s, Helweg-Larsen joined the Waffen-SS in 1941. "An estimated 75% of the 6,000 Danes who enlisted in the Waffen-SS were Nazi sympathisers, but there's nothing to indicate that Helweg-Larsen joined for ideological reasons," explains Henrik Skov Kristensen, head curator of the Danish National Museum and a leading authority on wartime Denmark. "He was an anglophile, he loved jazz, and he deeply admired Ernest Hemingway. However, shortly before war broke out he began to develop a certain sympathy for Germany and, during his service in the SS, he developed an admiration for Germany and the German people."

On the afternoon of 24 September, this happy-go-lucky member of the Waffen-SS Kurt Eggers propaganda unit invited Brownscombe, his two fellow British medics, Brian Devlin and James Logan and British army chaplains Daniel McGowan and Alan Buchanan along with Waffen-SS officers Karl-Gustav Lerche and Ernst Beisel for drinks in the officers' mess. "We sat there and drank some bottles of red wine, apricot brandy and whisky," Helweg-Larsen later told a British army interrogator. "The conversation was friendly. I interpreted for the two Germans."

After a while, the two other Waffen-SS officers left, while Helweg-Larsen kept drinking with the Brits. "We were all pretty merry, but Brownscombe was the most sober of the party or carried his drink best," Helweg-Larsen told the interrogator. The group parted company at dusk, and Helweg-Larsen invited his new friend Brownscombe over to the SS officers' living quarters for a last drink "to show him that the SS were not so bad as English propaganda made out."

Some 10 people including Lerche gathered at the SS billet, and "we drank and sang English and German songs." Afterwards, a driver took Helweg-Larsen and Brownscombe back to the hospital. They stepped out, still chatting away, sharing stories and agreeing to stay in touch after the war. "He said I was too good to be in the SS and I said he was too good to be in the English Army," Helweg-Larsen recalled. The evening's goodbye was a lengthy one, as they kept shaking hands and patting each other on the back then continuing their conversation. During one such handshake, the Dane reported, Brownscombe collapsed in front of him, dead.

Suddenly Lerche appeared, holding a pistol. When the Dane asked what had happened, Lerche said that he'd had to do it, adding that Brownscombe had a happy death. Though Helweg-Larsen had himself killed a Danish newspaper editor several years earlier, he remonstrated with Lerche: "[Brownscombe] had been our guest and you had drunk with him." Rather bizarrely, the pair left the dead officer on the ground, where his fellow POWs found him. The next day, Father Buchanan buried Brownscombe and placed a wooden cross on his grave.

Unravelling Lerche's Lies

The following September, with the war recently over and allied forces occupying Berlin, Charlotte Bormann walked into a British military office to inquire about her son, a Waffen-SS soldier named Lutz Bormann, who was now in British custody. To her surprise, the official responding to her queries showed none of the hostility she was expecting. "I asked him why he showed me such remarkable kindness," she said later.

Soon the Waffen-SS mother learned that the 'British' official was in fact a Waffen-SS officer named Karl-Gustav Lerche, who had been widowed and lost his children – or so he told her – following an allied bomb attack on the city of Weimar. The pair quickly became lovers; Lerche moved in with Bormann. But soon there was trouble: a friend of Bormann's reported that Lerche's wife and children were not only still alive but living in Berlin. Lerche told Bormann that he was in love with her and dispatched her to tell Mrs Lerche that he wanted a divorce. Bormann duly delivered the news to Mrs Lerche, to which the latter retorted that she didn't want her husband back anyway "as he [was] a scoundrel".

"I asked Mrs Lerche if her husband having been in the SS was that terrible, to which she responded, 'Don't you know that my husband killed an Englishman?'," Bormann later said. "I said, 'All German soldiers shot people and your husband was obviously a soldier as well.' She responded that he was a scoundrel who'd shot an English officer from behind, that's what she'd heard from [the British Army] and the Secret Service, who'd paid her a visit the day before."

Meanwhile Brownscombe, whose murder had never been solved, was beginning to haunt his killer. Armed with this startling information, Bormann returned home and announced to her lover that she was leaving him. But, pleaded Lerche, the very same day he had overheard a captain in his office saying on the phone, "He murdered a British officer!" Lerche was certain that he would be arrested the next day. Visibly upset, he told his mistress the real story of Brownscombe's death, explaining that during their alcohol-infused night the two men had become good friends, shaking hands and agreeing to meet up after the war, but that he had had no choice but to follow an order to shoot the Englishman. It must have been a convincing act, because Bormann decided to stay with Lerche. Indeed, she became his main accomplice as he took on a new identity to evade British investigators.

But which identity to choose? Bormann volunteered that of her long-deceased second husband Dr Samter. ("I told him that if all else failed, he could become a Jew," Bormann told the police.) Lerche eventually assumed the identity of Günther Breede. Breede and Bormann, having moved to Munich, established a seemingly ordinary domestic life. Occasional get-togethers with former Waffen-SS colleagues provided the only hints of Lerche's past.

The Last Betrayal

Back in England, meanwhile, the Brownscombe family grieved. "I think Brian's murder fundamentally changed my grandfather," says Pitcher. "He was my grandparents' oldest child and their only son, and, in the family, he had a heroic stature as he'd not only attended a public school, a stretch for them, but also become a doctor." Uncle Brian, decorated for saving a soldier from drowning in the Mediterranean, says Pitcher, "had a very good war until the moment he had a very bad one".

Yet, tragic though a family member's death may be, the Brownscombe family faced a reality shared by hundreds of thousands of families after the end of the war: a son, daughter, father, mother killed for no reason, in a murder never solved or even investigated. "The only German officers and soldiers prosecuted by German courts were ones who had killed deserters or other German soldiers," explains Sönke Neitzel, a professor of international history at the London School of Economics. "The United States only prosecuted a handful of US soldiers, and Canada and Italy didn't prosecute any of their own."

But Brownscombe's case was reopened and the family has Lerche's skirt-chasing habits to thank. Anger over Lerche's affairs appears to have motivated Bormann to kick him out and spill the beans to the police.

On 10 December 1952, Munich police arrested the veteran Nazi. "Jail!" the reporting officer has written in large letters at the top of the neat, type-written form, the beginning of an extremely ambitious investigation spanning three years and much of Europe. "This is the only case I know of where a German WWII soldier or officer has been prosecuted by a German for a single murder," says Neitzel. "Even Heinz Reinefarth [known as the Henchman of Warsaw] got a negligible sentence. The real wealth of prosecutions only started in the 70s and 80s."

The challenge of prosecuting war crimes in civilian courts is, of course, that linking perpetrators of mass crimes to individual victims is extremely difficult. So-called 'minor' crimes, the killing of one or two people, are easier to prosecute, but given the numbers involved – some 900,000 men served in the Waffen-SS alone – they required the testimony of Bormann. "Sometimes wronged wives would go to the police and report their husbands' war crimes," notes Edith Raim, a lecturer at the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich. "It was often thanks to acts of personal revenge that 'minor' crimes came to the attention of the police."

Final Testimony

Last year, after establishing a new definition of criminal responsibility, German authorities charged 30 Nazis with war crimes. And this September, the Simon Wiesenthal Centre supplied German authorities with the names of 80 members of the Einsatzgruppen (Nazi death squads) who could be charged with murder according to the new rules. Given the age of the alleged war criminals – most are in their 90s – this may be the last gasp of Second World War justice and retribution.

Following the anonymous tip-off regarding Lerche (which, he remained convinced, came from Bormann), the detectives in Munich showed remarkable investigative zeal. Lerche's voluminous criminal files, now stored in a Munich archive, reveal an assistant detective called Göschel making sometimes daily inquires over the course of three years, as Lerche kept changing his story.

This is Lerche's final version of events: born in Mühlhausen, Thuringia, in 1912, he trained as an electrician before joining the Hitler Youth, becoming a freelance writer for Nazi publications, joining the NSDAP [Nazi party] and founding a Nazi magazine. Aged 22, he married his wife Emmi, though he told the Munich detectives that he couldn't remember the name of the church. Later, as a war reporter with the SS's Kurt Eggers propaganda unit, Unterscharführer, Lerche was sent both to France, the Soviet Union, Italy and Holland.

What does an SS man do when the war ends? Lerche told the police that towards the end of the war, his Waffen-SS rank and uniforms had been replaced by military ones. More likely, he simply bought a military uniform to evade detection, a move that paradoxically helped him get a job with the British military. "[My driver and I] volunteered our services as an administrative assistant and driver, respectively, and the Englishmen accepted," he said.

Lerche told the police the same story that he'd told Bormann: that he had shot Brownscombe on orders from an unnamed commander, as the Germans were abruptly retreating and couldn't accommodate a POW in their midst. In reality, the Germans stayed several days longer. Still, Lerche's account of the fateful evening, as told to the Munich detectives, hints at the peculiar atmosphere at Arnhem, with officers communing as a guild while at the same time being captors and captives.

"I went with Larsen to the POW camp in Arnhem, where we talked with several [POW] English officers," recalled Lerche. "After our conversation, war-reporter Larsen invited one of the officers, a captain or lieutenant colonel whose name was not known to me, to [the German] quarters, a villa in Arnhem. There, Larsen talked with the Englishman for some time, while I was in another room. Then Larsen and the Englishman came into my room and Larsen said that the Englishman wanted to say goodbye to me. We said goodbye, whereupon the Englishman wanted to walk back to the POW camp alone. I told Larsen that this was completely impossible, because if the Englishman walked alone he could be shot by any sentry without warning. I gave Larsen the command to bring the Englishman back to the camp in the official car. After a while, the driver returned and said that the camp had been dissolved and that Larsen and the Englishman were waiting in front of it."

Lerche then describes a sequence of events in which he wants to ask the field gendarmerie to take Brownscombe with him only to be told that this would be a burden and that "the prisoner should be killed".

"I said, 'Obersturmführer, that's completely impossible!'" Lerche told the police, "and he responded, 'What do you mean impossible, I'm giving you the official order to shoot this man dead, do you understand?' [ . . . ] I then went back with Körber [his driver] to the camp, where Larsen was waiting with the Englishman. I pulled out my pistol but put it back into the holster as I didn't feel capable of carrying out this order." But moments later, his resolve strengthened, Lerche "pulled out the pistol again and shot the Englishman once from the side".

Lerche on Trial

On 17 March 1955, Lerche's trial finally began. "He killed the British officer, to whom he had pretended to show emotions of friendship, because from his political perspective he considered a POW enemy officer not worthy of life," the prosecutor declared. The prosecution had made remarkable efforts to bring witnesses to Munich: McGowan had arrived from Peterborough outside London, Logan from Glasgow, Buchanan from Belfast, and Devlin from Singapore.

The prime witness, however, was dead: in January 1946, Brownscombe's fateful friend, the Hemingway-and-jazz-loving Helweg-Larsen, had been executed for the murder of Carl Henrik Clemmensen, a Danish newspaper editor. In his place, the German prosecutors had decided to call British Army investigator Arthur E Reade, who had questioned Helweg-Larsen. He proved a somewhat reluctant witness: "I should be glad to attend [the Munich Court] to give evidence in the above case, subject to the payment of my first class travel and hotel expenses and a daily allowance," he wrote to the prosecutor.

Still, Reade turned up in Munich with Brownscombe's friends. During the trial, Lerche finally admitted that there was no order to kill Brownscombe but argued instead that he'd simply been drunk. The court ruled that the heavy drinking along with the fog of war clouded the Waffen-SS officer's judgement. On 16 December, Lerche was found guilty and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

"He simply had bad luck," says Neitzel. "Generals who shot thousands of people got less jail time." But as a French diplomat says in German novelist Kurt Tucholsky's 1932 short story Französischer Witz (French wit): "The war? I can't find it so terrible. The death of one person: that's a disaster. Hundreds of deaths: that's a statistic!"

Upon learning of the verdict, the Brownscombe family found it unfathomable that Lerche's drunkenness should count in his favour. And in the end, Brownscombe's killer didn't even serve his 10 years. After clemency letters from people ranging from Lerche's elderly mother in East Germany to the Stille Hilfe, an SS veteran support organisation run by SS chief Heinrich Himmler's daughter, Lerche was released on 25 February 1960, having only served half his sentence.

Seventy years after Arnhem, Brownscombe's family still considers that a travesty. Was Brian's life only worth five years? But 70 years after the Warsaw Uprising, neither Commander Reinefarth nor any of his subordinates have served jail time for the slaughter that claimed the lives of over 200,000 Polish civilians and soldiers (along with the lives of 16,000 German soldiers) and levelled the beautiful Polish capital.

The hospital that was to become the final step in Brownscombe's promising career still stands – though these days it contains luxury apartments, not doctors and patients. As for George Pitcher, who grew up in the shadow of heroic-and-mysterious Uncle Brian, he sees a certain humour in Lerche's fate: "There's a certain irony in the fact that a member of the Bormann family helped Brian get some justice."