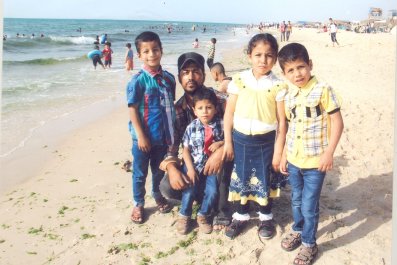

Earlier this fall, a tribal leader from Anbar province in Iraq slipped across the border with Jordan and headed to the capital city of Amman for a series of meetings with regional intelligence and military officials. Ahmed al-Shammari had been part of the Sons of Iraq movement, the so-called Sunni awakening in 2006 that ultimately wrested control of large swaths of western Iraq from Al-Qaeda. He and other tribal leaders throughout the province had worked closely with American troops in those days, convinced they had a long-term commitment: that the U.S. could be counted on, that they were "the strong horse," as al-Shammari would say later.

He was wrong, he now acknowledges, on all counts, and in Amman he would make his displeasure clear at a meeting with a U.S. special forces officer he had worked with. The message he was delivering was simple: On October 5, 23 tribes in Iraq and Syria were going to declare their allegiance to the Islamic State (commonly known as ISIS). They had not been attacked—not yet, anyway—so were not doing so under duress. They were taking sides without a shot having been fired. At one point, al-Shammari took out the so-called unit coins he had been given by the various U.S. Army battalions he had worked with over the years—tokens of their appreciation—and tossed them on the ground in disgust. "What good are these now?" he said. "All they represent are broken promises."

In the war that now engulfs Iraq and Syria, little complicates the United States's efforts to defeat ISIS more than the loss of the Sunni tribes as allies—people who, in Iraq, were pivotal in turning the Iraq War around when it seemed headed for the abyss in 2006. Getting them back should be a strategic priority for the U.S., yet it is not clear that can be accomplished, particularly if Washington is serious about minimizing the "boots on the ground" this time around.

The dilemma is acute: Few in the U.S. have an appetite for getting more deeply involved militarily in Iraq yet again. But as Sinan Adnan (a pseudonym for an Iraqi national in Baghdad) and Aaron Reese put it in a recent report for the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), a Washington think tank, "a military campaign to destroy ISIS'' that does not reverse Sunni loyalties in Iraq, far from bringing the country back from its descent into sectarian civil war, "will instead accelerate that descent."

The Sunnis—a minority in Iraq, at slightly less than a third of the population, but an overwhelming majority in Syria—now view the central government in Baghdad as a puppet of the Iranian regime and believe the U.S. is working closely with Iran against not just ISIS but against Sunni influence in the region as well. They believe—despite Washington's adamant denials—that the crucial influence of Iran-controlled Shiite militias, recent Iranian airstrikes against ISIS (on the same day U.S. bombers hit targets in Syria) and the Obama administration's evident desire to get a nuclear agreement with Tehran are all the proof anyone needs. "Are we even discussing this as if it's a matter of debate?" asks a former Saudi government official.

This suspicion—which "you can magnify tenfold among Sunnis inside Iraq," says the Saudi official—makes even a post-ISIS future for the country extremely problematic. Intelligence sources in the region note that there are several armed Sunni groups now fighting alongside ISIS—including hard-core jihadist militias like the Jaish al-Mujahedeen—that are unlikely to ever be reconciled with a central government in Baghdad. There are also, they note, mainstream Sunni tribes under ISIS's sway, but Arab intelligence agencies believe they could conceivably be moved, at minimum, to a position of neutrality toward Baghdad's central government, but only if two very big things happen: ISIS is defeated and the Iraqi government under new Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi makes a sustained good-faith effort to draw the tribes back in.

"A political accommodation in Baghdad that appeals to Iraq's Sunni population is essential," says Adnan.

The skepticism among Iraq's Sunni neighbors that any of this will happen is, at this point, overwhelming. "Too many things at this stage have to happen for one to envision that kind of scenario," says a senior intelligence official in the region. Most of the momentum at this point is in the other direction: a fundamental split between Sunni and Shiites that starts in Iraq and spreads throughout the region.

How We Got Here

In the spring of 2005, as the situation in Iraq deteriorated rapidly, I met a Jordanian intelligence officer with whom I had struck up a relationship in Baghdad. At one point over drinks—the last time I would see him in the Iraqi capital—he said, "Congratulations. Your country went to war in Iraq. And Iran won."

He was not joking, and he was right. It is hard to overstate the mistrust among Sunnis—in and outside of Iraq—for the government in Baghdad, even though, under U.S. pressure, al-Abadi has appointed both defense and interior ministers more acceptable to many tribal leaders. Consider: The government of Anbar province, in the Sunni heartland in Iraq, is now contemplating buying weapons from Saudi Arabia and Jordan, rather than waiting on Baghdad and the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) to defend them. The deepening Sunni-Shiite divide, says one regional intelligence officer, "is one of the defining geopolitical facts that we all confront."

The other is a United States that, under President Barack Obama, had decided to lower its profile in the region, only to be dragged (oh so reluctantly) back into Iraq and Syria. Obama thought he was done with the former in December 2011 (when the last U.S. troops left), and decided against attacking the Syrian government after it used chemical weapons on its own people (having said previously that was a "red line" that could not be crossed).

Both decisions were at least defensible. Administration officials point to the failure to reach a so-called status of forces agreement with Baghdad—which would have left a residual U.S. force in the country and arguably provided more of an opportunity to pressure then prime minister Nouri al-Maliki to lighten up on the Sunnis. They say al-Maliki would not allow any agreement to go to the Iraqi parliament for fear it would be voted down. That is the excuse the Obama administration uses for the full-fledged withdrawal—and will be the excuse former secretary of state Hillary Clinton uses when her expected presidential campaign begins in earnest.

Syria was then, and remains, a violent mess, and an air campaign designed to decapitate Bashar Assad's government would have, if successful, led to a bloody and chaotic conflict, without the U.S. having an obvious side to back, according to the administration's defenders. Here, the decision to depose Muammar el-Qaddafi—and the chaos in Libya afterward—was a cautionary preamble. In this view, Obama's walk around the White House grounds with Chief of Staff Denis McDonough and the subsequent decision to punt on Syrian airstrikes is a profile-in-courage moment for the president. No one had ever answered persuasively the "then what?" question, and the president's defenders say they still haven't.

The predominant view in Sunni-dominated countries—which are ostensibly U.S. allies—could not be more starkly different. To say they are dismissive of the Obama administration now is putting it mildly. Contemptuous is more like it. Never, to be sure, supporters of the original decision to invade and occupy Iraq, the country's neighbors are furious at the power vacuum the Obama administration left, in their view, in the country once American troops pulled out. That Iran would come to dominate a blatantly sectarian government under al-Maliki was, they say, predictable. (His defenders, including some in the U.S., argue that this is revisionist history. They note, among other things, that in 2008 al-Maliki led Operation Knights Assault, a vicious military campaign to root out the Mahdi Army, a large Shiite militia, from the southern city of Basra.)

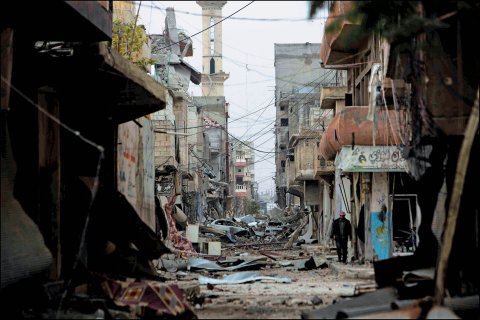

It's undeniable that sectarian tensions in the country steadily increased after the U.S. pulled out. They reached a breaking point in April of last year in Hawija, a town in Kirkuk province, between Baghdad to the south and Mosul to the north. Protests among Sunnis had occurred there since January, as they became more and more marginalized under al-Maliki. On April 19, members of the ISF's 12th Army division entered a protest site to disperse the crowd. What happened next is unclear. Some say armed protesters opened fire on the security forces. Others say the soldiers shot first. Whatever the case, dozens of protesters were shot dead.

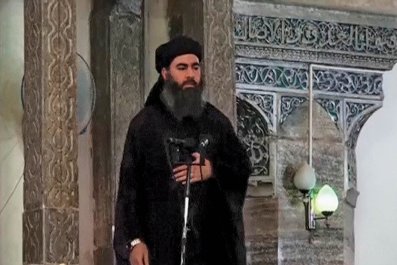

The political impact of the so-called Hawija incident was electric. Influential tribal leaders who were still seeking negotiations with al-Maliki's government gave up. Men like Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the man who heads ISIS, were gaining influence. And they issued a call to arms.

The result, a year and half later, is bloodily apparent. The Sunnis went to war with Baghdad, and the tribes—including several that had previously sought an accommodation with the central government—signed on. Of the six people who formed the military council of ISIS in Iraq, five came from major tribes in the Sunni heartland. By no means were they all hard-core Salafist-jihadi fanatics, like al-Baghdadi. Three of them had been high-ranking officers in Saddam Hussein's army.

Cut to Syria. According to Hussain Abdul-Hussain, a prominent Kuwaiti journalist with deep ties to Sunni tribes throughout the region, on November 2, 2013, 14 clans that had been loyal to Assad's government pledged their allegiance to ISIS. This included several tribes in Raqqa, which Assad's forces then controlled. It is now the headquarters of ISIS. The shift, Hussain says, "was nearly bloodless."

What changed? According to Hussain, the calculus was simple. Tribes look for the "strong horse," and in both Iraq and in Syria, that was al-Baghdadi and ISIS. "The myth is that there are radical Sunni tribes and moderate Sunni tribes. The tribes are not moderate or radical. Tribes hedge and look for the strongest power," he says. At the time, he notes, the U.S. derided opposition groups fighting Assad in Syria as "carpenters, teachers and dentists" and hesitated to arm them. Washington was not in the game, so the decision became easy.

"They concluded we were not serious. We came, we left. The only strong power they could join," Hussain says, "was ISIS."

The dilemma the Obama administration now faces—and given how daunting it is, it will likely confront whoever his successor is two years hence—is straightforward: Retaking and stabilizing the vast swaths of territory now either controlled or contested by ISIS in Iraq and Syria requires buy-in from the Sunni tribes that are either undecided or now openly supporting al-Baghdadi. But as Michael Pregent, a former U.S. Army intelligence officer now at the National Defense University, argues, that buy-in is unlikely going to come "absent a protracted [U.S.] military commitment without an end date. Ideally, we have to reestablish leverage, but how do we do that if we're not there? The answer is, we don't."

Even if the U.S. and its allies can degrade ISIS from the air—and there is significant skepticism in the region that they can, particularly without the cooperation of the tribes—the next problem becomes the other armed Sunni groups that oppose Baghdad and want no part of the ISF in the Sunni heartland. And, their Sunni neighbors argue, for good reason: Under al-Maliki, the ISF in the past four years went from being 55 percent Shiite and 45 percent Sunni to 95 percent Shiite. "That's got to change radically, but the question is, Will the Iranians let Abadi do it," says a regional intelligence official.

Armed Sunni groups—some Salafist jihadis, some (like the Iraqi Baath party faction of Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri, who was a high-ranking figure in Saddam's regime) more secular—will continue to drive sectarian conflict in the country no matter what happens to ISIS. That, many in the region believe, is part of the legacy of America's withdrawal in 2011. About 300 representatives of these groups gathered in Amman last July to try to figure out whether to cooperate with ISIS or to confront it, and to plot their own future. (The Jordanian government claimed publicly to have had nothing to do with the conference.)

The tenor of the group's deliberations—and a whiff of what a post-ISIS future holds—came from the statement al-Douri's group issued at the conference's end. It called for the elimination of the new Iraqi constitution, the dismantling of the country's security forces and the annulling of anti-terrorism laws that the group perceived to be anti-Sunni. Essentially, the group called "for a reset of Iraq back to 2003," says Adnan, author of the ISW report on Sunni insurgent groups. The bottom line, several sources told Newsweek, is that these groups now have the legitimacy in the eyes of mainstream Sunnis that many of the politicians who cooperated for a time with al-Maliki now lack. "They are now the Sunni mainstream," says one Middle Eastern military official who until recently was posted in Baghdad.

The Obama administration and its allies are now focused on rolling back ISIS's gains in both Iraq and Syria. U.S. military officials view ISIS as the most globally ambitious of all the armed Sunni groups, a tacit way of saying they'll happily deal with other groups if and when the time comes. The other factions of the armed Sunni rebellion might, in other words, actually be the "Jayvee," as Obama rather awkwardly described ISIS earlier this year. (The term refers to a junior varsity team—meaning second-string. Obama used the term in an interview with The New Yorker, distinguishing ISIS from Al-Qaeda.)

For now, the bombing campaign has been intensified, and what looked like an Iraq-centric approach to the war against ISIS has now been expanded. More than 3,000 U.S. troops have been deployed as advisers, and this month Secretary of State John Kerry said Washington would be in the fight against ISIS for as "long as it takes."

Sunni sources in the region acknowledge that they got at least a sliver of encouragement in September, when Obama appointed retired Marine General John Allen as the special envoy to the global coalition to defeat ISIS. Allen had been a key deputy in Iraq to General David Petraeus, architect of the surge and the Anbar awakening from 2006 to 2008. Former Army intelligence officer Pregent says the Anbar tribes were practically "begging" for Allen to come back to the region to "restart" the awakening. The issue, he says, is whether Allen "will be empowered" to do that.

Sunni-dominated governments in the region privately believe that would require a significant increase in the number of American "boots on the ground," and are skeptical that Obama—or his successor—will make that call. A tribal leader from Anbar puts it bluntly: "We have to believe that the U.S. and the coalition is the winning side. That [the tribes] can trust the United States, and that this is a long-term commitment. Can you do that? We don't think so. And unless you do, you are no longer the 'strong horse;' the jihadis are. So we are dealing with reality." And that reality, he concludes wearily, "probably means another decade of war."