Jamal Benomar was worried. Late last month, he was talking to me on the phone as he waited to fly to the Persian Gulf. Yemen was on the verge of collapse, and Benomar, the United Nations special envoy to the country, was hoping to bring its warring factions together.

For years, the Moroccan-born British diplomat had been warning international leaders that stabilizing Yemen's internal politics was critical to defeating Al-Qaeda. But as he landed in Yemen last month, the country, which is heavily divided over religious, tribal and other alliances, continued to crumble. "Maybe now," Benomar said, the world "will listen."

In January, the Houthis, an armed group in northern Yemen, allegedly with ties to Iran, tightened their grip around the capital city of Sanaa. Gunmen surrounded the presidential palace and trapped the Western-backed leader, Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi, at his nearby residence.

The news sent shudders across the region, where many already fear Iranian influence. After speaking with Benomar, the U.N. Security Council released a unified statement, supporting Hadi. The Saudi-backed Gulf Cooperation Council, a regional body of Arab countries, later did the same, calling Hadi's ouster a "coup" and vowing "all necessary means" to return him to power.

To no avail. On January 22, Hadi, along with Prime Minister Khaled Bahah and the rest of the Yemeni government, resigned. And Benomar began scrambling to meet with local leaders—from tribal elders to business tycoons—to try to peacefully end the crisis.

His task remains daunting. Not only are many in the Gulf and the West worried about Iran gaining a foothold in Yemen; they're also concerned the Houthis may be able to exploit sectarian tensions and hinder America in its war against Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

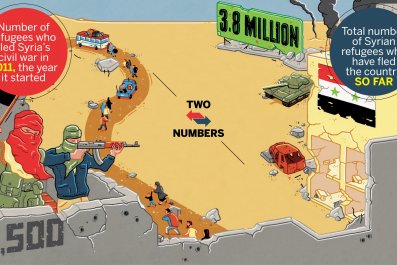

Benomar—and Yemen—have been at this crossroads before. In 2011, the Arab Spring spread to the streets of Sanaa, as protesters forced longtime strongman Ali Abdullah Saleh to step down. He was once considered a linchpin in the fight against terror, but the U.S. turned against him after the protests and now considers him untrustworthy.

Not long after Saleh's ouster, Benomar, along with other diplomats and a coterie of Yemeni leaders, helped steer the country toward peace. In 2012, the nation elected Hadi in what many observers called a remarkably inclusive political process. Yemen, a country largely known for chaos and qat, a local stimulant, was now being hailed as a promising experiment in democracy. And the government in Sanaa seemed even more committed than Saleh was to fighting terror.

Indeed, with Hadi's backing, the CIA and U.S. Air Force increased their use of killer drones to hunt down suspected Al-Qaeda terrorists. As President Barack Obama put it in a September 2014 speech, the U.S.'s "strategy of taking out terrorists who threaten us, while supporting partners on the front lines, is one that we have successfully pursued in Yemen."

But not everyone was happy with the new government. Namely the Houthis, who objected to a proposed constitution that would set up a federal system and divide the country into six regions. "They wanted more territory, with natural resources and access to the sea, under their control, and they couldn't get it," said Nidaa Hilal, a former U.N. consultant in Yemen.

The Houthis are members of Yemen's Zaydi sect, a Shiite offshoot, which some observers compare to Hezbollah, Iran's Lebanese proxy, which boasts both a militant and a political wing. The comparison isn't completely apt (unlike Hezbollah, the Houthis operate only inside Yemen). But like Lebanon's Party of God before it, the Houthis' rise came by way of force, not democracy. Last year, armed Houthis started moving south from their mountainous enclaves in the north, an operation that culminated in January's coup.

For those who once had high hopes for the Arab Spring in Yemen, the Houthis' takeover has left them feeling bitter and jaded. "The Houthis almost want to make Yemenis regret overthrowing Saleh," said Farea al-Muslimi, a Yemeni writer and activist.

Washington is also concerned. Despite news reports to the contrary, the U.S. hasn't halted its drones program in Yemen. Late January, American drones killed three suspected Al-Qaeda operatives in the Marib province in northern Yemen. But with the Houthis in control of Sanaa, the White House may be forced to try coordinating counterterrorism moves with a group whose slogan is "Death to America, death to Israel, curse on the Jews, victory to Islam."

As we spoke on the phone, Benomar mentioned Chérif and Saïd Kouachi, the brothers who attacked French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in January. Several years ago, at least one of them reportedly traveled to Yemen to train with Al-Qaeda. The 12 people the Kouachis killed in Paris were painful reminders of how chaos in the Middle East can easily reach Western shores.

With armed gunmen patrolling the streets, the turmoil in Yemen is unlikely to subside anytime soon. Because the Houthis are a Shiite offshoot, their power grab has put Yemen's majority Sunnis on edge, which could be a recruitment boon for Al-Qaeda, a predominantly Sunni group.

Not everyone is pessimistic. Some say the Houthis will find it hard to govern and stoke sectarian tensions at the same time. "The Houthis will increase the pool [of recruits] for Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula in the short term," said Al Sharjabi, a member of Yemen's reformist Al-Watan party. "But eventually, you can't run the country this way."

Perhaps. But for now, Benomar must try to communicate with 16 political groups that agree on practically nothing. Going forward, he said, the Houthis will try to plant their loyalists as "No. 2's" in a variety of government ministries. And the trick will be to find a credible leader who can run the country without being intimidated by the men with guns.

Saleh, the fallen dictator, apparently has some ideas. He's kept his hand in Yemen's politics from afar and has been working with some members of the Houthi leadership. He's allegedly pushing for an early presidential election so that his son, Ahmed, can emerge the winner. That, reformers say, would almost certainly bury any hope for political progress.

After years of trying to get everyone to pay attention to Yemen, Benomar finally has a captive audience. The only problem: It may be too late.