The refugee who arrived by himself in Sweden last year gave his name as Han Song. He said it was an alias as he fears reprisals from the North Korean government. Home, Han told Swedish authorities, is North Korea, a place he has reportedly escaped. Via a string of helpers and smugglers, Han says he managed to reach China and then traversed Russia hidden in a Trans-Siberian Railway car, finally crossing into Sweden in a truck, hidden behind its cargo. But Sweden's migration board, Migrationsverket, has ruled that the young man is lying and plans to deport him to China. Han's growing number of supporters say the officials have made a terrible mistake.

The first question is whether Han is really North Korean. If, as he claims, he really is a street child who managed to not just cross into China but to journey all the way to Sweden, his would be the most spectacular North Korean escape in history, more remarkable even than that of Shin Dong-hyuk, who claimed to have escaped into China from a North Korean prison camp and who has since recanted several aspects of his story. But following an analysis of Han's speech, Migrationsverket has ruled that he didn't speak with the accent of his purported home region and is, in fact, Chinese.

His lawyer disagrees. "After getting to know Han intimately over a long period of time, my team and I are completely convinced he's North Korean," says Arido Degavro. "Only somebody who has spent a long time in North Korea can have the detailed knowledge that he has. But he knows close to nothing about China and doesn't speak Chinese." Han says that his mother died of cancer when he was little and that his father is a political prisoner. That left the boy, who gives his current age as 17, a de facto orphan.

Tim Peters, an American based in Seoul, from where his HHK/Catacombs network helps North Koreans to escape, has been providing expertise on North Korean defectors' escapes and accents to Han's legal team. "Our efforts have centred on helping find the truth about his identity as well as suggesting ways to avoid the most dangerous outcome," he explains. "We found that veteran activists and former defectors alike from his claimed home area responded conclusively that the boy's patterns of speech were consistent with the North Hamgyeong dialect and with someone who had spent time in China as a wandering orphan."

That analysis contradicts the findings of Sprakab, the language identification contractor used by Migrationsverket, which, after interviewing the teenager, decided that he was not a native (North) Korean speaker. In interviews with Migrationsverket, Han also appeared to be unfamiliar with his purported home region. But when queried by Swedish Radio, the linguist who conducted Sprakab's analysis said she was sure that the young man does in fact speak North Korean at a native-speaker level. (Sprakab could not immediately be reached for comment.) According to Degavro, the reason Migrationsverket couldn't find the towns Han had mentioned was that the official who transcribed them had taken the names down incorrectly. Degavro says that the towns can easily be found on Google Maps.

Despite this apparently glaring error, Migrationsverket insists on deporting Han to China because he hasn't been able to prove his identity, as required by Swedish law. Degavro, who has now filed a second appeal against Migrationsverket's decision, and is awaiting a final ruling by the end of February, notes that a frightened teenager from a totalitarian regime is hardly in a position to prove his identity in interviews with officials. Adds Peters, whose underground network has in the past several weeks helped three North Korean families escape: "Migrationsverket's apparent unflagging determination to send him to China, of all places, where he will face the spectre of forced repatriation to North Korea, is the kind a response that we have come to expect from Vietnam, Myanmar or Laos, who all have cosy relationships with North Korea, not a Western nation with the sterling human rights record of the likes of Sweden."

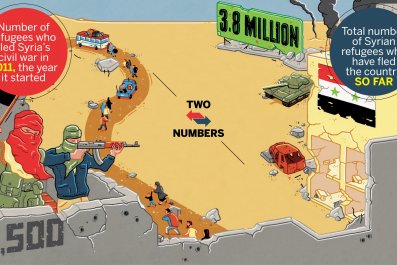

Still, Migrationsverket's scepticism is not irrational. Over the past decade, the number of unaccompanied children seeking asylum has grown from 388 in 2004 to 7,049 last year. During the first two months of January, the figure has doubled compared with January 2014, with the majority of the children arriving from Eritrea and Syria. According to EU statistics, Sweden is now Europe's most popular destination for child asylum seekers, with Germany a distant second. The vast majority of child asylum seekers arriving in the EU are male teenagers. Unaccompanied children have better chances of being granted refugee status than adults and families arriving together, and receive more support from the Swedish government once they've been given asylum.

Dentists and doctors are frequently called in to help determine the age of arriving children through examination of their teeth and wrist bones. "It's often hard to determine whether a young person is 17 or 19," Migrationsverket's head of legal affairs, Fredrik Beijer, says. "They do have to prove their identity, but we also have to take into account that they're young and may not be able to explain every detail. We can also ask paediatricians for their judgements, but they feel uncomfortable about participating beyond putting a tick in a box." Beijer says Migrationsverket couldn't determine Han's age but nevertheless categorised him as minor.

Based on such exams, Migrationsverket ruled that 280 of the unaccompanied minors who arrived in Sweden last year were, in fact, adults. Degavro sees why the immigration agency might be sceptical of the claims of a male teenager arriving in Sweden alone, but notes that claiming North Korean nationality wouldn't help an asylum seeker stay in Sweden, as such cases are typically referred to South Korea. Here Han's story takes a new turn. As his supporters note, North Koreans caught in China are habitually sent back to their home country, where an uncertain fate awaits them. But, Beijer says, even though Migrationsverket has determined that the young man is Chinese, Sweden may never extradite him to China. That's because Swedish immigration laws require proof. With few other details known about the young man, Migrationsverket will have to undergo a lengthy investigation, during which Han is entitled to stay in Sweden. Beijer adds: "If he proves that he's from North Korea, we may be able to send him to South Korea." The two Koreas immediately grant citizenship to refugees from the other side.