Sport is war minus the shooting. So said George Orwell. All the same, shooting is a pretty big thing to take out of a war: and if you live in a war-zone, any part of life that is minus the shooting has an irresistible attraction. That explains at least some of the passion for cricket in Afghanistan.

It's a craze of dramatically recent origin, and yet it already plays a serious role in national identity. Cricket has become an expression of hopes of national unity, national recognition, national achievement and at the bottom of it all, peace. Life minus the shooting. Afghanistan have, for the first time, qualified to play in the cricket World Cup, which takes place in Australia and New Zealand. Afghanistan play their first match, against Bangladesh, on 18 February. They also have matches against Scotland, Australia, New Zealand and Sri Lanka. They are minnows all right: but minnows with the attitude of sharks.

Cricket has been played in Afghanistan for years and it hasn't meant much more than cricket in California or baseball in Croydon. There's a record of British troops playing in Kabul in 1839, but that's not got much to do with the explosion of cricket in Afghanistan in the 21st century.

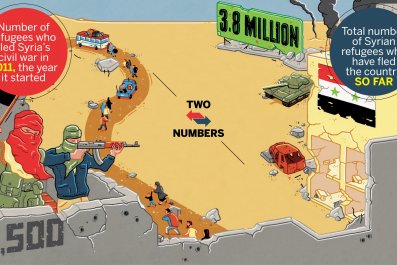

When they took control, the Taliban banned all sport in Afghanistan. Then they relented: cricket became the one sport they permitted. But cricket didn't become a major part of Afghan life until the Taliban fell in 2001. Now here's a strange fact: whenever you find people recovering from a disaster, in survival camps after earthquakes or floods, in refugee camps where inmates have fled from war and persecution, you find hope. Hope expressed in the form of sport. For every disaster there's an inspiring, heartbreaking photo of children shooting hoops or kicking a football against a backdrop of ruins. So the Afghanis who fled the Taliban and became refugees in Pakistan got to play cricket. It was inescapable, cricket being part of the turbulent Pakistani soul.

So when the Taliban fell, the refugees returned with cricket in their baggage. The game spread across the country like an internet virus, for it seemed to express an essential and unquenchable part of Afghan identity. At its most basic level, these primordial Afghani cricketers revelled in whirlwind bowling and extravagant hitting. Everything was approached with flat-out full-on intensity; no hanging back, no guile, no thinking things through. Just the great gladiatorial contest between hurtling ball and flying bat.

That is the story of cricket as a national meme. But that's not enough to get you to a level of competence in international sport, a place without forgiveness. And yet, in a warm-up tournament held in mid-January before the World Cup, Afghanistan, though beaten by Scotland, went on to beat Ireland by 71 runs, with Najibullah Zadran, coming in down the order, hammering 83 runs off 50 balls – a powerful performance at any standard of the game. More pleasing than his explosive hitting was the composed and unflustered bowling performance that followed: a passage of play in which the Afghani players used their heads and pressed home their advantage in the manner of case-hardened professionals.

That is what the national side is now aiming at: to make the transition from cheery underdogs to serious sportsmen. They've now reached a level in which they are frequently brilliant against teams at their own level, though they still tend to be overawed and out of place against the leading cricket nations. They are coached by a New Zealander, Andy Moles, who used to play for Warwickshire in England. His brother, a security consultant, told him not to go, but he's been a huge success. Peter Andrews from Queensland coaches at academy level, Jason Douglas of South Africa works on fitness training. There are now indoor training facilities in Kabul.

Afghanistan became an associate member of the International Cricket Council (ICC) in 2013; they now get an annual subsidy of $850,000. They are acutely aware of their naiveté, which is shown by lack of physical fitness, panicky batting with a talent for run-outs, and bowlers who lose heart at setbacks. Now they're toughening up – acquiring greater cricket-savvy skills, thinking like pros and preparing in the best way. But the urge to play sport on the biggest stage is not without its romanticism. A step closer to the top teams would be a great achievement.

It's been a remarkable business. To go from a cricket-free nation to borderline contenders with proper recognition from the world governing body in 14 years is astonishing. It tells of great natural talent and considerable national ambition. It's been said that a low-flying plane crossing modern Afghanistan navigates from one cricket match to another: all spread out below in the vast spaces that have seen generations of horrors perpetrated by Americans, Russians, jihadis and the Taliban. The most eloquent counter-argument to them all is in this curious game.

The Indian writer Ashis Nandy famously said that cricket is an Indian game that was accidentally invented in England. It might also be true that cricket is the Afghani game – much more so than the polo-like game they play, using the body of a dead goat for the ball – even though it was accidentally invented in England. Afghanistan will need to beat Bangladesh and Scotland plus one of the big boys if they are to proceed to the second stage of the World Cup – highly unlikely. Qualifying at all is triumph enough to be going on with. Any victory in any match will be something to cheer. Subsequent progress will be hard. Bangladesh provides a classic example of a cricket nation full of promise that stalled and rolled back. In Afghanistan, politicians and power-mongers like a voice in team selection these days: by seeking to be associated with success such people are capable of destroying it.

But this is no time for pessimism. Afghanistan have made it to the World Cup: an astonishing achievement for a country that had only just taken up the sport and little short of miraculous for a war-zone. It's one of those stories that makes sport agnostics admit that there are times when it seems to have a point.