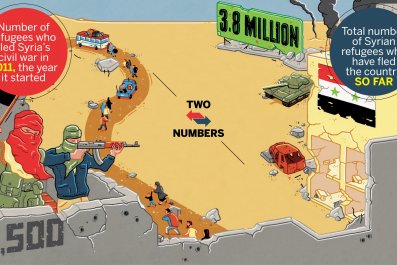

Just before Christmas, Atheel al-Nujaifi, a leading Iraqi politician, quietly slipped into Washington, D.C., with an urgent request that the White House provide arms and training for his 10,000-man Sunni militia. For seven months now, the United States has been bombing Iraq and Syria, trying to beat back the so-called Islamic State (ISIS). But dislodging the world's most notorious jihadist group hasn't been easy, and Nujaifi was offering to help. The governor of Iraq's Nineveh province, he was forced to flee last summer when ISIS militants overran the country's Sunni-dominated north and west. In meetings with American officials, Nujaifi warneda that unless the United States and its allies can quickly liberate the parts of Iraq under ISIS control, people there may soon learn to live with the militants. "Time," he said, "is not on our side."

Other Sunni leaders appear to be following his lead and asking the U.S. to support their militias, which they claim are willing to take up arms against the jihadist group. The White House is still weighing Nujaifi's request, but in a sign of where things may be headed, U.S. and Canadian special forces are training some 5,000 former Sunni policemen from Mosul at a camp that Nujaifi set up near Erbil, in Iraq's autonomous Kurdish region.

The scramble to join the fight recalls the vaunted sahwa, or "awakening" of 2005, when Sunnis joined forces with the U.S. to root out Al-Qaeda's affiliate in Iraq, the precursor to ISIS. And it comes as U.S. and coalition forces are training thousands of members of the Iraqi Army and Kurdish forces for a ground offensive this spring. Many American veterans of the first awakening say a second round isn't a bad idea. "We need allies," said James F. Jeffrey, who served as the charge d'affaires, then ambassador to Iraq during the American occupation. "If you're looking for a Sunni face to put on any kind of offensive, this is helpful." Patrick Skinner, who served as a CIA officer in Iraq, agreed. "Right now, there are a lot of bad options in Iraq," he said. "This might be one of the better ones."

A second awakening also would help advance an important U.S. goal in Iraq: Integrating Sunnis back into the Iraqi military and government. A minority group in Iraq, Sunnis have long feared that leaders in Baghdad are doing the bidding of their Shiite neighbors in Tehran. After U.S. combat troops withdrew in 2011, sectarian tensions flared as former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki reneged on his promise to incorporate Sunni fighters into the army, cracked down on Sunni politicians and allowed Shiite militias to terrorize Sunni towns. When ISIS fighters stormed into Iraq last summer, the group exploited local anger and alienation, and convinced some Sunni former military commanders to join its ranks. With Washington now pushing for a nuclear accord with Iran, and cooperating with its longtime adversary in the war against ISIS, some Sunnis remain highly suspicious of allying with the Americans.

Since Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi has been in office, the U.S. has pushed a plan to form national guard brigades in Iraq's 18 provinces, largely to encourage Sunnis in the western and northern parts of the country to defend their territory. A bill to create these brigades has been bottled up in the country's Shiite-dominated parliament, so in the short-term, some experts say, a new awakening could help bring Sunnis into the fold. "What Nujaifi and the other Sunnis are effectively saying is, 'OK, if we can't go the national guard route yet because it's getting hung up in Parliament, let's do this informally and get Sunnis into the battle, fighting and feeling like they're part of the reconquest of Iraq," said Kenneth M. Pollack, an Iraq expert at the Brookings Institution who met with Nujaifi in Washington.

Nujaifi isn't the only influential Sunni looking to take part in this reconquest. Last month, a group of political and tribal leaders from Anbar Province in Iraq's Sunni heartland met with Vice President Joe Biden at the White House to discuss ways they could help combat ISIS. The delegation included Anbar Governor Sohaib Al-Rawi and Sheikh Abu Risha, the head of the Iraq Awakening Council.

Another prominent Sunni leader joining the fray is Mudhar Shawkat, a former member of Parliament and an old-line patrician. Now living in London, where he fled in 2012 to escape death threats from Shiite supporters of Maliki, Shawkat says his followers include Sunni luminaries such as former Lieutenant General Ra'ad al-Hamdani and former Major General Nouri al-Dulaimi, both highly respected Iraqi commanders now living in exile in Jordan. "We can put forward a really big force very, very easily," he told Newsweek. "All we need to do is get these generals to go on the radio and ask people to sign up as recruits, and there will be tens of thousands of them."

Shawkat said he plans to hold a conference in Erbil later this winter that will include hundreds of former Sunni Iraqi officers, along with the leaders of Iraq's largest and most influential Sunni tribes. Shawkat said that, during an upcoming visit to Washington, he will ask the Obama administration to send an observer to the event. Eventually, he said, he would like the U.S. to endorse his militia to win funding from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. "The American role is essential," he said. "I don't think anything can happen without the Americans."

But a second Sunni awakening is only a good idea if the U.S. can be sure the Iraqi warlords appealing for arms, money and training can muster the necessary strength to defeat their jihadist foe. In Shawkat's case, it's not clear if the former military commanders and prominent tribal figures he claims as allies are on his side. "If I were the U.S. government and I were assessing this, I would ask, does this guy really have a force?" Pollack said. "I'd say, 'You want us to arm, equip and train your men? Show me the men. Give us the names.'" Pollack said U.S. officials also need to determine if the Sunnis seeking American assistance are proxies for other regional players, like Turkey, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and even Iran. "There are a lot of different questions you want to ask before you start training these guys," he said.

Pentagon planners say 50,000 troops, backed by U.S. airpower, are needed to break ISIS's hold. They hope to do this by cutting off ISIS supply lines from Syria, besieging the militants in Mosul and other Iraqi strongholds, and then systematically picking the jihadis apart. But since the Iraqi army and Kurdish units now being trained amount to a force about half the necessary size, adding more men to the mix is critical. The 5,000 Sunni policemen now being trained outside Erbil are a good start. And given the Sunnis' eagerness to join the fight—and the White House's aversion to sending U.S. combat troops back to Iraq—there's a good chance other Sunni militias may bring the anti-ISIS force up to full strength.

Sunni leaders know that a savage battle lies ahead, and many warn that if the counteroffensive works, they won't repeat the mistake they made after the first awakening, when they stood by as Maliki ran roughshod over them. This time, these Sunni leaders say, they'll demand a quasi-autonomous region, defended by their own militia, much like the arrangement the Kurds enjoy with the federal government.

Shawkat envisions an Iraq composed of self-governing Sunni, Shiite and Kurdish regions, with Baghdad serving as the country's capital inside a federal zone. It's an idea that President Barack Obama rejects, but Biden and many Iraq experts have long championed. "There is no other solution," Shawkat insists. "There has been too much blood, too much destruction. Now we need to make the best of what we have."

Pollack agrees with the idea of breaking Iraq into three federal regions, but strongly doubts Abadi and the ruling Shiites would ever allow the Sunnis to form a semi-autonomous area. Any such move would effectively remove a third of the country from Baghdad's control, yet still require the Iraqi government to pay all its bills. Unlike the Kurdish region, the Sunni areas have no oil and therefore little means to contribute to the treasury. "It's a terrible deal," Pollack says. Yet without separation, he says, Iraq's Shiites and Sunnis could remain locked in a sectarian war.

Nujaifi, however, remains committed to the old Iraq. Though he's a prominent Sunni figure, he rejects the idea of a semi-autonomous state, saying he's confident Abadi will work to make Sunnis feel part of the country. "This isn't the time to talk about autonomy," he says. "First, we Iraqis all have to come together to defeat ISIS."