The story goes that Alan Ladd, a huge star in 1946, complained to the producer of a war picture that was about to start shooting: "Just for a change, can I have a finished script before I start? I'm tired of having 30 or 40 pages thrust at me and being told I'll get the rest." When assured that he would have what he asked for, Ladd thanked him and added, "An actor likes to know what wardrobe he's got to have."

The annals of Hollywood are filled with such gags told at the actor's expense—and they're usually told by writers, since they write everything and often get the last laugh (if not the money and prestige). "It's the Pictures That Got Small": Charles Brackett on Billy Wilder and Hollywood's Golden Age (Columbia University Press) is filled with such jokes and characterizations. Brackett, a producer and screenwriter best known for his collaborations with Wilder (The Lost Weekend, Sunset Boulevard) used his diaries (1932 to 1949) to cast a light on the life of a lowly movie scribe (albeit one of the most successful of his time), while catching the scenery around him in all of its sparkle and shadow.

"His work in recording the day-to-day working life of a Hollywood studio is comparable to that of Samuel Pepys in the seventeenth-century documenting a crucial period—the Restoration—in British history," writes editor Anthony Slide in his introduction. "Like Brackett, Pepys had wide-ranging interests, with his diaries mingling the personal with the impersonal." So we get the rumblings of the age off-screen (the Depression, the buildup to America's involvement in World War II, the Hollywood blacklist) and the author's impressions of stars such as Ginger Rogers ("She hasn't a very good brain but insists on using it") and Charlie Chaplin ("as repellent a human being as I've ever been in the room with") and literary figures slumming for money like F. Scott Fitzgerald ("He seemed burned-out, colorless, amazing when one remembers the blaze of his youth") and Aldous Huxley ("Frankly, I detest this writer, whose work I worship.… "). Starting with his arrival from New York, where he wasThe New Yorker's first drama critic and a novelist of some renown and had a seat at the Algonquin Round Table, Brackett's diaries read like a funnier, better-paced version of Barton Fink.

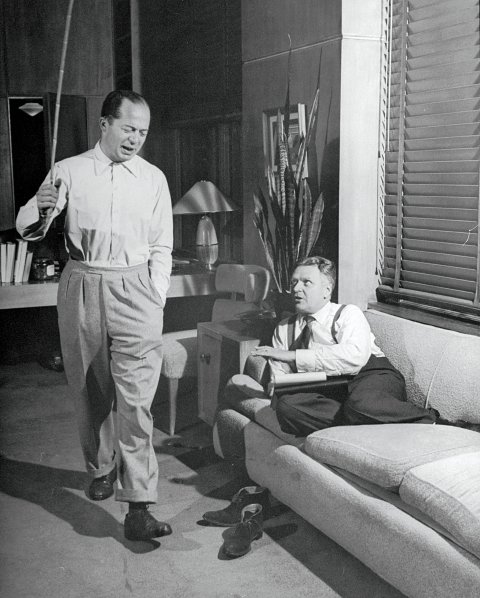

But he saved his best stuff for his relationship with Wilder. Life magazine called them, "The Happiest Couple in Hollywood," and their union yielded 12 movies (and many more, unproduced scripts) but like many such partnerships, it wasn't easy. "The comparison of Brackett and Wilder to husband-and-wife writing teams is not a wild one," writes Slide, "for in many ways the two men functioned as husband and wife—agreeing and disagreeing in their relationship as much as would any married couple." And when they finally parted company, after the struggle to make Sunset Boulevard, Wilder said "something had worn out and the spark was missing. Besides, it was becoming like a bad marriage."

The two couldn't have been more different. Wilder, an Austrian-born Jew who fled Germany during the rise of Hitler, was politically liberal and a tireless womanizer. Brackett's father was a New York state senator and his family traced its roots back to the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He was a Republican WASP, casually anti-Semitic in his jottings, unable to write about his wife's alcoholism and (perhaps) a closeted homosexual. He despised the faux proletariat in tinseltown, sniffing of Elia Kazan, when he won a best director Oscar (for Gentleman's Agreement) in 1948, "he hadn't the grace to wear a dinner coat. Social protest, I presume." And when Brackett won an Academy Award in 1946 for co-writing The Lost Weekend, he records "a compliment from [gossip columnist] Hedda [Hopper] which went right down to the dark springs of snobbism and pleased me mightily, something to the effect that 'it's so wonderful you should have overcome the advantages of gentle birth and come to this.… I looked at all the other people on the stage and there wasn't another top drawer person among them, male or female.'"

Brackett and Wilder were contract writers at Paramount in 1936 when they were thrust together to work on an Ernst Lubitsch comedy,Bluebeard's Eighth Wife. Their styles were different but ultimately complementary. "Brackett wrote repartee," wrote Maurice Zolotow in Billy Wilder in Hollywood. "He hated story conferences. He hated talking out imaginary scenes with directors and producers. Wilder loved those moments. The burden of story conference strategy fell upon his glib tongue."

Lubitsch was considered the master of the lost art of the screwball comedy, and Bluebeard belonged in an equally extinct subgenre Zolotow labeled "the UFF, or Unfinished Fuck" picture in which the heroine (Claudette Colbert), "a compulsive virgin," frustrates the amorous hero (Gary Cooper)—even after they are married. To convey such a story under the strict code of the Motion Pictures Association of America of the time, when even married couples slept in separate beds on screen and no one kissed with their mouths open, was the first challenge the two faced and the results were deemed such a success that soon everyone wanted that Brackett-Wilder touch.

Their writing styles, too, were completely divergent. "He is a hard, conscientious worker, without a very sensitive ear for dialogue, but a beautiful constructionist," Brackett writes of his partner in September 1936. "He's extremely stubborn, which makes for trying work sessions, but they're stimulating." By November he has learned of working with his "temperamental partner.… The thing to do was suggest an idea, have it torn apart and despised. In a few days it would be apt to turn up, slightly changed, as Wilder's idea. Once I got adjusted to that way of working, our lives were simpler."

Soon the pair were known for doing the impossible, as they collaborated with Lubitsch again on Ninotchka (1939), the story of a humorless Soviet apparatchik (Greta Garbo) who falls in love with a Western playboy (Melvyn Douglas) in Paris. In Hollywood at the time, you were called a "social fascist" or a "Red baiter… if you didn't admire Joseph Stalin or ridiculed the USSR," writes Zolotow. This was before Stalin's pact with Hitler, though rumors of the show trials and mass executions taking place in Russia were already the best way to start an argument among show people. How, then, make Garbo (somebody not known for comedy) a sympathetically funny figure—though not a figure of fun?

It was Wilder's idea to take the tale to Moscow, where they could depict in semi-realistic fashion the living conditions of Soviet citizens at the time. Ninotchka shares an apartment with a cellist and a streetcar conductor; the love letter she gets from Douglas has been completely redacted; and when three friends come to have dinner with her, each brings his own egg. The contrast between her life there and the Champagne and caviar dream of Paris spoke volumes.

Despite their skill for comedy, Brackett and Wilder wanted to push themselves. It was Wilder's idea to translate Charles Jackson's 1944 novel about an alcoholic writer in Manhattan to the screen, a subject for which Brackett initially showed little enthusiasm. "Nowhere in the diaries is the word alcoholism used to describe [his wife's] condition, nor does he attempt to detail her depression," writes Brackett's grandson, Jim Moore in his foreword. "At most, he will mention that she has gone back East, where a Western Massachusetts clinic took her in for care."

And it didn't stop there: One of Brackett's daughters became an alcoholic, and married one herself. She died after falling down the stairs, while he died in a fire after he'd passed out. And Wilder, who, like his partner was not much of a drinker, was mystified by the behavior of one of his famous collaborators, Raymond Chandler, who worked with him on Double Indemnity (1944). "[One] day he was living in reality and the next he would fall into a spell of morbid gloom and become incomprehensible to Wilder," wrote Zolotow. "Billy Wilder made The Lost Weekend to explain Raymond Chandler to himself."

Much has been written about the making of the film (Blake Bailey wrote an entire book about Jackson, a somewhat pathetic figure whom Brackett delights in tormenting), and Brackett confines his notes less to the difficulties of capturing such grim material and more to the pressure outside forces, from AA to whiskey distilleries, tried to bring to bear on Paramount—and the inevitable inanities of the censors after it was made. "There was a great flurry from the Censorship Department about Jane Wyman's wearing a white sweater which they claimed was too revelatory," wrote Brackett on December 26, 1944. "One of the censors said it looked as though Wyman was trying to cure [Ray Milland] off the bottle by the nipple."

Whatever its subliminal messages,Lost Weekend swept the Oscars the next year, winning awards for the writers, Milland—and Wilder, for the first time, as director. Much like the alcoholic foreswearing drink, Brackett repeats (and repeats) that he will never work with Wilder again ("After all, an Oscar one night a year is agreeable, but is it worth looking at that face and listening to that ego all the other days in the calendar?")—only to be brought back together. Though Wilder had other writing partners after he and Brackett broke up (most notably I.A.L. Diamond, who co-wrote Some Like It Hot and The Apartment), the tension of their collaboration was unique and Sunset Boulevard was their fitting finale.

The original idea was Brackett's. "We're pretty well set on the raddled old picture star who is keeping a young man, probably a writer," he notes in August 1948. He envisioned a comedy but Wilder was pulling the story in a darker direction. "As writers—which was what they still considered themselves—Brackett and Wilder had reached the pinnacle of success," writes Zolotow. "They were at the $5,000-a-week salary level, individually, and that was the highest scale in 1948."

But the war, and the Communist witch hunts that followed, made the already jaded Wilder even more cynical, success or no. Brackett's wife, Elizabeth, had died a year before and the entry for June 7, 1947 is one of the most heartfelt in the book: "I held my dear girl's hand and, very quietly, more quietly than drifting to sleep, the breathing stopped and I was left with a sharp sense of aloneness, of realization of how I'd depended on that wise, ill woman, how she'd meant home and refuge from the foolishness of this foolish town.… "

Despite his loss, Brackett still wanted to make people laugh and the joke of having a dead writer tell the sordid tale of his doomed affair with a washed-up siren was the kind that appealed to both him and Wilder. Casting was a bitch—the old film stars they approached, including Mae West and Mary Pickford, resented the implication that they were has-beens and Montgomery Clift, the hot actor of the moment, bagged on them at the last moment. "I could swear someone he loves has said to him, 'You mustn't play that dreadful part,'" Brackett wrote in his diary—and indeed, the legendarily gay Clift "had been for some years in the grip of a romantic obsession with a woman about 30 years older than he was—Libby Holman, the famous torch singer of the 1920s," according to Zolotow. "Libby Holman had threatened to kill herself if Montgomery played such a role in this movie."

Which was how, with the accidental luck of many of Hollywood's great films, they ended up casting William Holden and Gloria Swanson ("Sic transit Gloria Swanson," was the one-line review of the film offered by one wag). Little else was left to chance, from the selection of the house in which she hides (actually at Wilshire and Irving, a few miles south of Sunset Boulevard) to the close-up Brackett insisted upon when Swanson uttered her most famous line: "I am big—it's the pictures that got small."

Brackett was equally adamant about casting the great silent film director Erich von Stroheim in the role of Swanson's chauffeur. Von Stroheim added humor of his own when a makeup man approached him for a scene in which he sets up the screen on which Norma Desmond watches her old films.

"Are you going to make up my ass?" von Stroheim asked him. "Because that's all that's being photographed."